ألكسندر كالدر (1898-1976)

الاصل

معرض بيرلز، نيويوركالمجموعة الخاصة ، التي تم الحصول عليها من ما سبق

معرض

معرض كرين، لندن، كالدر: الزيوت والغواش والهواتف المحمولة والمنسوجات، 5 آذار/مارس - 1 أيار/مايو 1992التاريخ

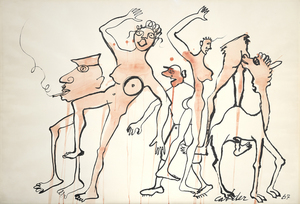

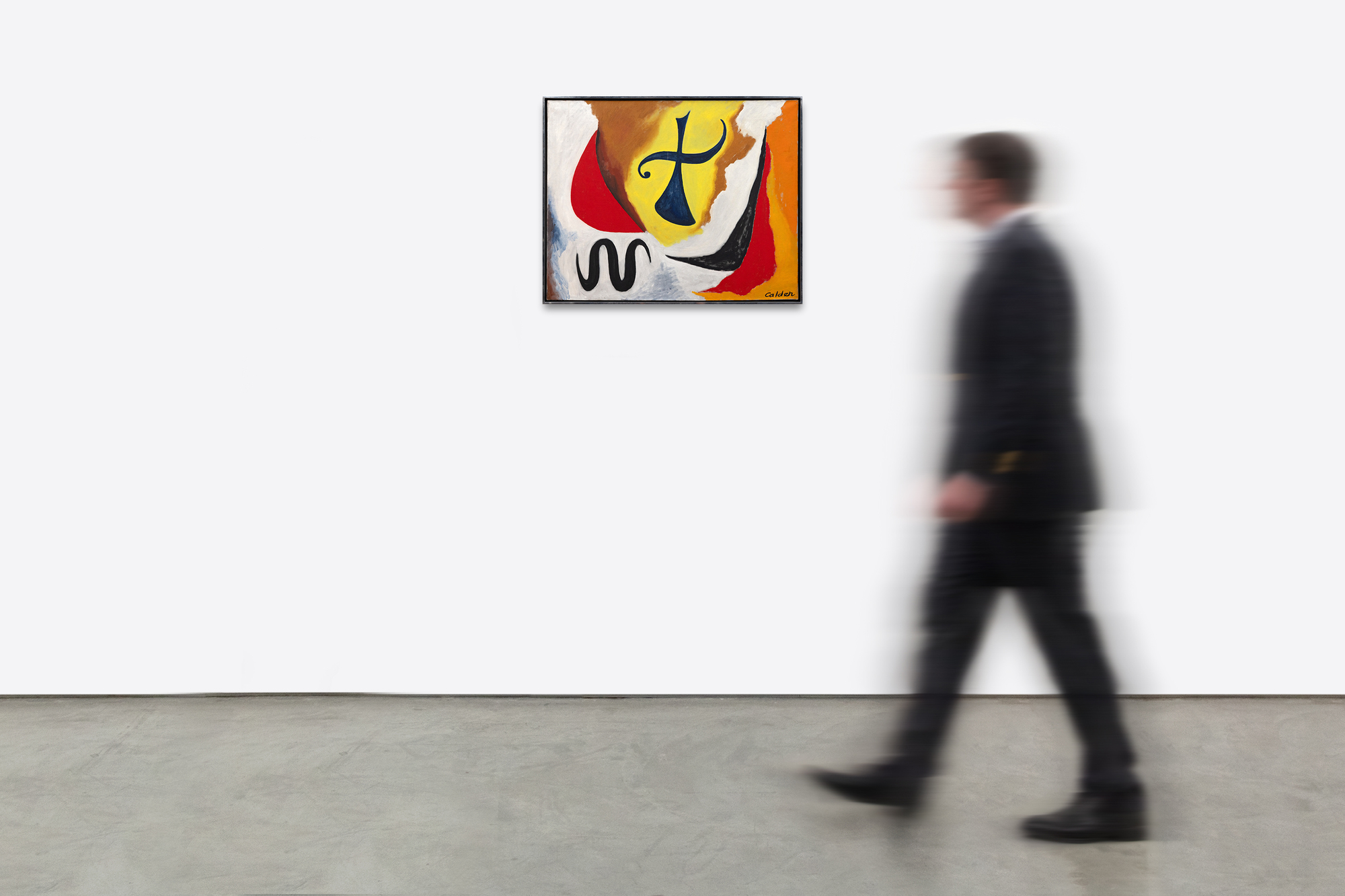

نفذ ألكسندر كالدر عددا مذهلا من اللوحات الزيتية خلال النصف الثاني من 1940s وأوائل 1950s. بحلول هذا الوقت ، تطورت صدمة زيارته عام 1930 إلى استوديو موندريان ، حيث لم يكن معجبا باللوحات ولكن بالبيئة ، إلى لغة فنية خاصة بكالدر. لذلك ، بينما كان كالدر يرسم الصليب في عام 1948 ، كان بالفعل على أعتاب الاعتراف الدولي وفي طريقه للفوز بالجائزة الكبرى للنحت في بينالي البندقية السادس والعشرين في عام 1952. من خلال العمل على لوحاته بالتنسيق مع ممارسته النحتية ، اقترب كالدر من كلتا الوسيطتين بنفس اللغة الرسمية وإتقان الشكل واللون.

كان كالدر مفتونا بشدة بالقوى غير المرئية التي تحافظ على حركة الأشياء. بأخذ هذا الاهتمام من النحت إلى القماش ، نرى أن كالدر بنى إحساسا بعزم الدوران داخل The Cross من خلال تحويل طائراته وتوازنه. باستخدام هذه العناصر ، ابتكر حركة ضمنية تشير إلى أن الشكل يضغط للأمام أو حتى ينزل من السماء أعلاه. يتم تضخيم الزخم المصمم للصليب بشكل أكبر من خلال تفاصيل مثل أذرع الموضوع الممدودة بشكل قاطع ، وناقل curlicue الشبيه بالقبضة على اليسار ، والشكل السربنتين الظلي.

يتبنى كالدر أيضا خيطا قويا من التخلي الشعري في جميع أنحاء سطح الصليب. يتردد صداها مع اللغة البصرية الهيراطيقية والشخصية المميزة لصديقه العزيز ميرو ، لكنها كلها كالدر في الرسوم المتحركة الفعالة لعناصر هذه اللوحة المختلفة. لم يحصل أي فنان على رخصة شعرية أكثر من كالدر ، وطوال حياته المهنية ، ظل الفنان مرنا بشكل بهيج في فهمه للشكل والتكوين. حتى أنه رحب بالتفسيرات التي لا تعد ولا تحصى للآخرين ، حيث كتب في عام 1951 ، "أن يفهم الآخرون ما يدور في ذهني يبدو غير ضروري ، على الأقل طالما أن لديهم شيئا آخر في عقلهم".

في كلتا الحالتين ، من المهم أن نتذكر أن الصليب تم رسمه بعد فترة وجيزة من اضطرابات الحرب العالمية الثانية ويبدو للبعض أنه انعكاس واقعي للعصر. الأهم من ذلك كله ، يثبت الصليب أن ألكسندر كالدر قام بتحميل فرشاته أولا للعمل على أفكار حول الشكل والبنية والعلاقات في الفضاء ، والأهم من ذلك ، الحركة.

رؤى السوق

- يظهر الرسم البياني الذي أجرته Art Market Research أنه منذ يناير 1976 ، زادت قيمة الأعمال الفنية لكالدر بنسبة 5068.8٪. خلال فترة السنوات الثماني نفسها ، كان معدل العائد السنوي لقطع كالدر 8.7٪.

- في الرسم البياني الثاني ، نرى أن قيمة أعمال كالدر الفنية قد زادت بنسبة 66٪ منذ نوفمبر 2014 ، مما أدى إلى تحقيق معدل عائد سنوي قدره 6.3٪.

- في حين أن كالدر كان فنانا غزير الإنتاج ، فإن اللوحات الزيتية على القماش مثل الصليب هي من بين أندر الأمثلة على عمل الفنان.

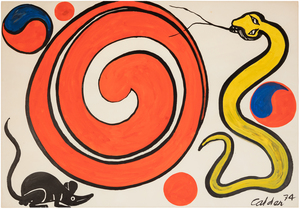

لوحات مماثلة تباع في مزاد علني

تم بيع فيلم "Personnage" (1946) مقابل 1,865,000 دولار أمريكي.

- رسمت قبل عامين من الصليب

- ألوان مماثلة ، لكن التجريد في The Cross أكثر ارتباطا

- بيعت هذه اللوحة في مزاد علني في عام 2014 ، وستبلغ قيمتها أكثر من 3 ملايين دولار اليوم.

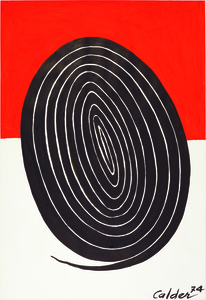

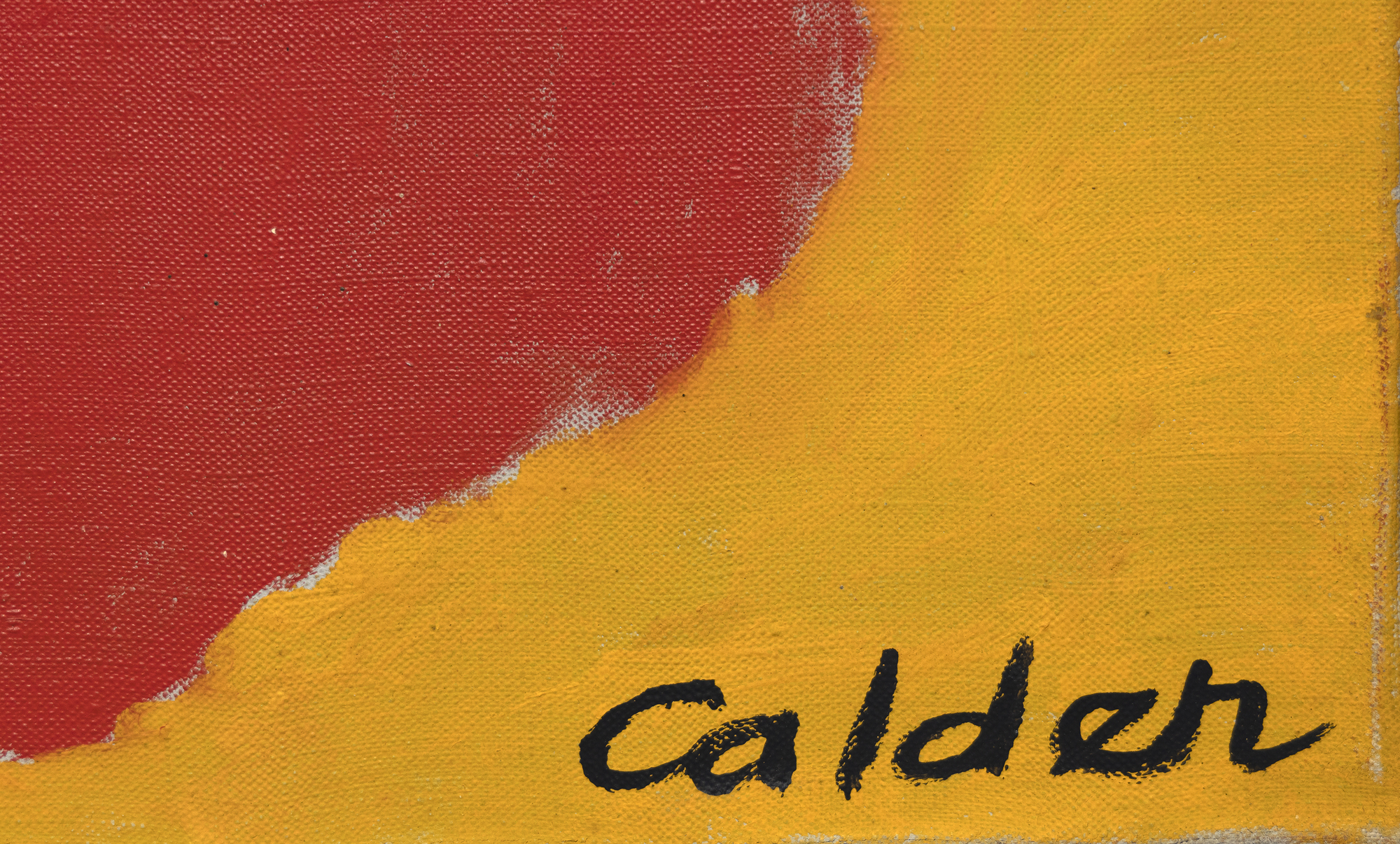

"Fond rouge" (1949) بيعت مقابل 1,815,000 دولار أمريكي.

- رسمت بعد عام واحد فقط من الصليب

- تجريد جميل ، ولكن ليس مثيرا من الناحية التركيبية مثل الصليب

- الخلفية هنا هي لون واحد فقط ، في حين أن The Cross يوازن بين ألوان متعددة في خلفيته