إميل نولد (1867-1956)

الاصل

يواكيم فون ليبل، نيوكيرشن، 1958مجموعة خاصة، ألمانيا

سوذبيز نيويورك، الانطباعية والفن الحديث مساء البيع: الثلاثاء, نوفمبر 2, 2010, Lot 00021

مجموعة خاصة، نيويورك

الادب

مارتن أوربان ، إميل نولد ، كتالوج Raisonné من اللوحات الزيتية ، المجلد. () المرجعان الثانيان، 1915-1951، لندن، 1990، العدد 1250، الصفحة 511 من النص الانكليزي.التاريخ

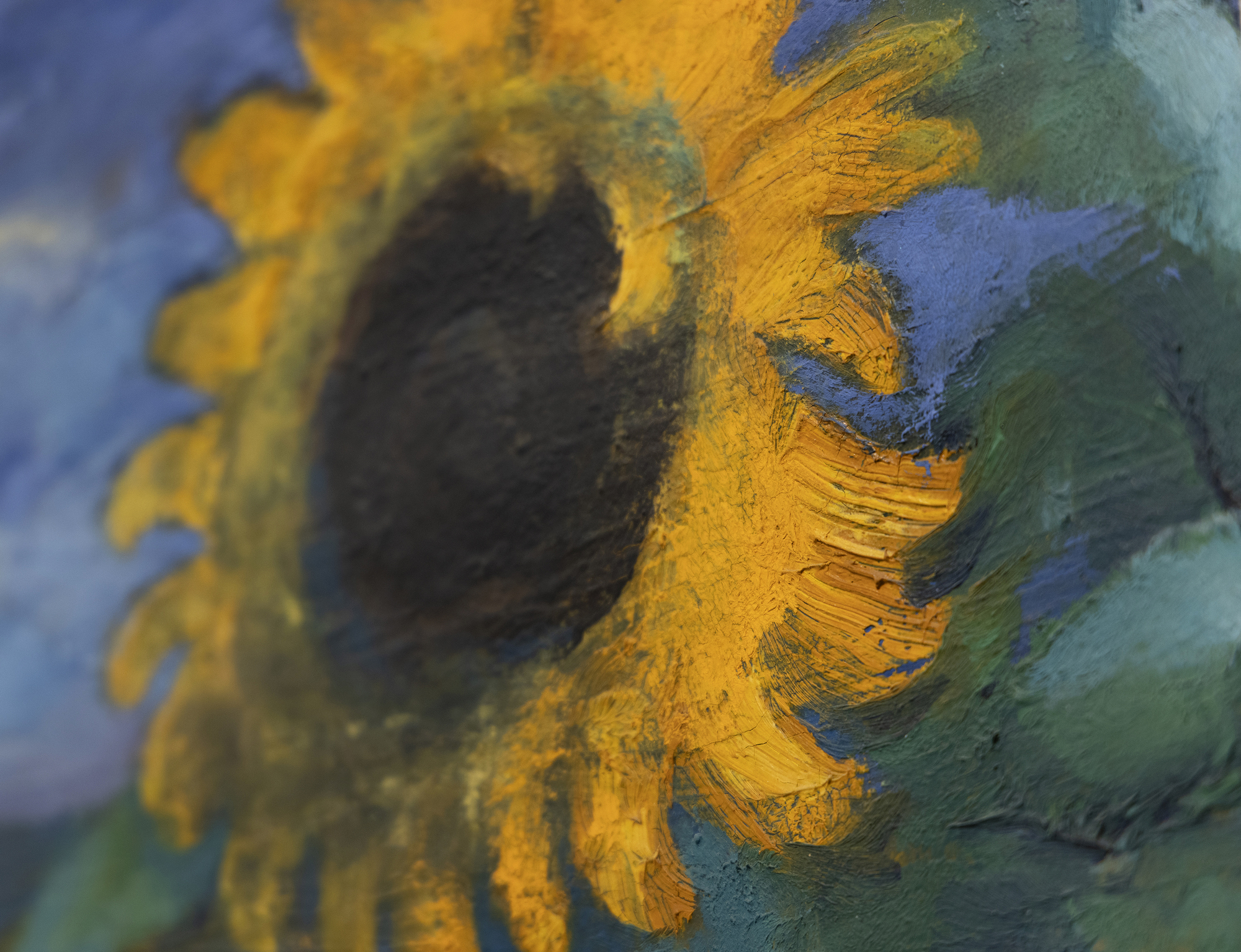

تدرب إميل نولدي كنجار خشب ، وكان عمره 30 عاما تقريبا قبل أن يصنع لوحاته الأولى. تشبه اللوحات المبكرة رسوماته ونقوشه الخشبية: شخصيات بشعة ذات خطوط جريئة وتناقضات قوية. كان الأسلوب جديدا ، وألهم الحركة الوليدة Die Brücke (الجسر) ، التي دعا أعضاؤها نولد للانضمام إليهم في عام 1906. ولكن ، لم يكن حتى أصبحت الحديقة موضع عمله بحلول عام 1915 أنه بنى على إتقانه لللمعان المتناقض للتركيز على اللون كوسيلة عليا للتعبير. في وقت لاحق ، ادعى نولدي أن "اللون هو القوة ، والقوة هي الحياة" ، ولم يكن بإمكانه أن يصف بشكل أفضل لماذا تعيد لوحاته الزهرية تنشيط إدراكنا للون.

الكثير من قوة حساسيات نولد اللونية الدراماتيكية الشبيهة بفاغنريان هي تأثير تنظيم الألوان الأساسية ، مثل الأحمر الداكن والأصفر الذهبي ل Sonnenblumen ، Abend II ، ضد لوحة كئيبة. يسلط التباين الضوء على لمعان الزهور ويعمقه ، ليس فقط بصريا ، ولكن عاطفيا أيضا. في عام 1937 ، عندما تم رفض فن نولد ومصادرته وتدنيسه ، تم عرض لوحاته على أنها "فن منحط" في جميع أنحاء ألمانيا النازية في صالات عرض ذات إضاءة خافتة. وعلى الرغم من هذه المعاملة، فإن وضع نولدي كفنان منحط أعطى فنه مساحة أكبر لالتقاط الأنفاس لأنه انتهز الفرصة لإنتاج أكثر من 1300 لوحة مائية، والتي أطلق عليها اسم "الصور غير المطلية". لم يكن مبتدئا في التعامل مع الألوان المائية ، فقد كان أسلوبه في الرسم المتدفق بحرية سمة مميزة لغسالاته الشفافة عالية الشحن منذ عام 1918. Sonnenblumen ، Abend II ، رسمت في عام 1944 ، هو زيت نادر في زمن الحرب. لقد أطلق العنان لخياله مع هذا العمل ، وزاد استخدامه لتقنيات الرطب على الرطب من دراما كل بتلة.

يعكس انشغال نولد الشديد بالألوان والزهور ، وخاصة عباد الشمس ، تفانيه المستمر لفان جوخ. كان على دراية بفان جوخ في وقت مبكر من عام 1899 ، وخلال 1920s وأوائل 1930s ، زار العديد من المعارض لأعمال الفنان الهولندي. كانوا يشتركون في حب عميق للطبيعة. وجد تفاني نولد في التعبير والاستخدام الرمزي للون امتلاء في موضوع عباد الشمس ، وأصبح رمزا شخصيا له ، كما فعل مع فان جوخ.

رؤى السوق

- نادرا ما تتوفر لوحات عباد الشمس المحققة بالكامل ، ومعظم أعمال هذا الموضوع موجودة في مؤسسات المتاحف.

- عندما طرحت لوحات الزهور في مزاد علني ، كانت من بين بعض أعمال نولد الأكثر مبيعا.

- كما يوضح الرسم البياني من Art Market Research ، فقد ارتفع سوق إميل نولد بنسبة 648.1٪ منذ عام 1976.

أفضل النتائج في المزاد

"Herbstmeer XVI" (1911) بيعت مقابل 7,344,500 دولار.

تم بيع فيلم "Indische Tänzerin" (1917) مقابل 5,262,500 دولار.

تم بيع فيلم "Rotblondes Mädchen" (1919) مقابل 3,826,851 دولارا.

"Sonnenuntergang" (1909) بيعت مقابل 3,517,759 دولار.

لوحات مماثلة تباع في مزاد علني

"مير الأول" (1947) بيعت مقابل 3,132,800 دولار.

- رسمت بعد ثلاث سنوات من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- أصغر قليلا من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- بدلا من الأزهار ، مير الأول هو منظر بحري ، وهو موضوع آخر قام نولدي بمراجعته بشكل متكرر خلال هذه الفترة.

تم بيع فيلم "Kleine Sonnenblumen" (1946) مقابل 3,042,500 دولار.

- رسمت بعد عامين من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- أصغر قليلا من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- يتميز أيضا بموضوع عباد الشمس

- تم تضمين هذه اللوحة في معرض نولدي الاستعادي لعام 2014 في متحف لويزيانا للفن الحديث ، الدنمارك

تم بيع "Üppiger Garten" (1945) مقابل 2,658,500 دولار.

- رسمت بعد عام واحد من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- أكبر قليلا من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- على الرغم من أنه ليس تصويرا لعباد الشمس ، إلا أن Üppiger Garten هو منظر طبيعي زهري مماثل مقصوص بإحكام

تم بيع "Grosse Sonnenblume und Clematis" (1943) مقابل 2,179,094 دولارا.

- رسمت قبل عام واحد من سونينبلومين ، Abend II

- أصغر قليلا من سونينبلومن، أبيند الثاني

- نفس موضوع عباد الشمس