Bitte kontaktieren Sie die Galerie für weitere Informationen.

Aktuelle Ausstellungen

2024

2023

2022

2021

2019

2018

Geschichte

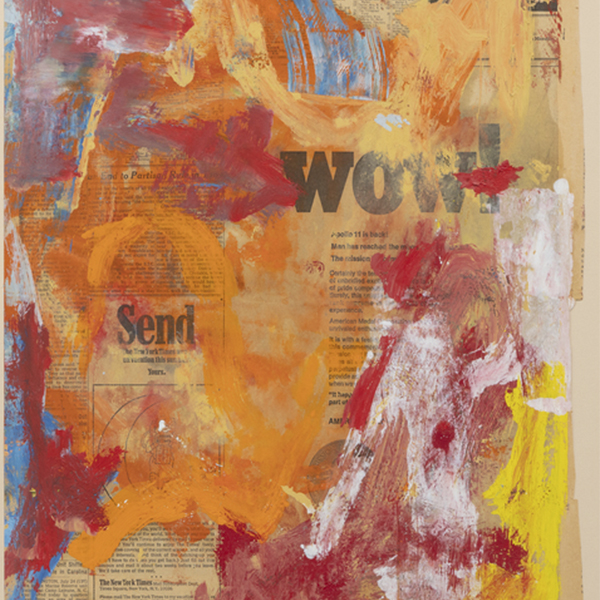

Nachdem er sich unwissentlich in das Gespräch über Pop Art mit seinem Großen Amerikanischen Akt Serie unwissentlich in die Pop-Art-Diskussion eingebracht hatte, erklärte Tom Wesselmann für den Rest seiner Karriere, dass es ihm nicht darum ging, sich übermäßig auf ein bestimmtes Thema zu konzentrieren oder einen sozialen Kommentar abzugeben, sondern dem, was ihn am meisten erregte, eine Form zu geben, die schön und aufregend war. Seine Serie der körperlosen Münder aus dem Jahr 1965 zeigte, dass ein Bild nicht auf fremde Elemente angewiesen sein muss, um Bedeutung zu vermitteln. Doch erst die Smoker-Serie mit ihrer verführerischen, fetischhaften Anziehungskraft verhalf ihm zu einem höheren Ansehen bei den wahren Sybariten. Abgesehen davon, dass Rauchen als cool und chic empfunden wird, ist ein Gemälde wie Smoker #21 die vollendete Feier von Wesselmanns Fähigkeiten als Maler. Vom wogenden Rauch angezogen, gab sich Wesselmann große Mühe, seine gewundenen Bewegungen genau darzustellen und die kurzen Pausen zu beobachten, die seine Wertschätzung für die sinnliche Natur des Rauches noch verstärkten. Wie alle großformatigen Werke Wesselmanns hat auch Smoker #21 die beeindruckende Präsenz eines Altarbildes. Es entstand in stundenlanger Arbeit in seinem beeindruckenden Atelier am Cooper Square in Manhattan, und das Ergebnis ist von schwüler Dynamik - beschwörend, sinnlich, verführerisch, glatt, üppig und vielleicht sogar unheimlich - ein Gemälde, das seine grafische Souveränität und seinen starken Realismus zur Schau stellt, garniert mit seinem patentierten Sex-Appeal-Flair.

Quelle: Bilder

Tom Wesselmann knüpft an den Erfolg seines Buches Großen Amerikanischen Akte aus, indem er sich auf einzelne Merkmale seiner Motive konzentrierte und 1965 mit seiner Mouth-Serie begann. 1967 machte Wesselmanns Freundin Peggy Sarno eine Zigarettenpause, während sie für Wesselmanns Mouth-Serie Modell stand, und inspirierte ihn zu seinen Smoker-Bildern. Die Rauchschwaden waren schwierig zu malen und erforderten, dass Wesselmann Fotografien als Ausgangsmaterial benutzte, um die flüchtige Natur des Rauchs richtig einzufangen. Die Bilder hier zeigen Wesselmann, wie er seine Freundin, die Drehbuchautorin Danièle Thompson, fotografiert, während sie für einige von Wesselmanns Bildvorlagen posiert.

Spitzenergebnisse bei Auktionen

"Great American Nude no. 48" (1963) wurde für 10.681.000 $ verkauft.

"Smoker #9" (1973) wurde für 6.761.000 $ verkauft.

"Smoker #17" (1973) wurde für 5.864.000 $ verkauft.

Vergleichbare Gemälde bei einer Auktion verkauft

"Smoker #9" (1973) wurde für 6.761.000 $ verkauft.

"Smoker #17" (1973) wurde für 5.864.000 $ verkauft.

Smoker #5 (Mouth #19) (1969) wurde für 4.703.900 $ verkauft.

Gemälde in Museumssammlungen

Museum für Moderne Kunst, New York

Kunstinstitut von Minneapolis

Dallas Museum of Art

High Museum of Art, Georgia

Crystal Bridges Museum für amerikanische Kunst, Arkansas

Cranbrook-Kunstmuseum, Michigan

Nasjonalmuseet, Norwegen

Museum für Kunst und Design der Präfektur Toyama, Japan

Authentifizierung

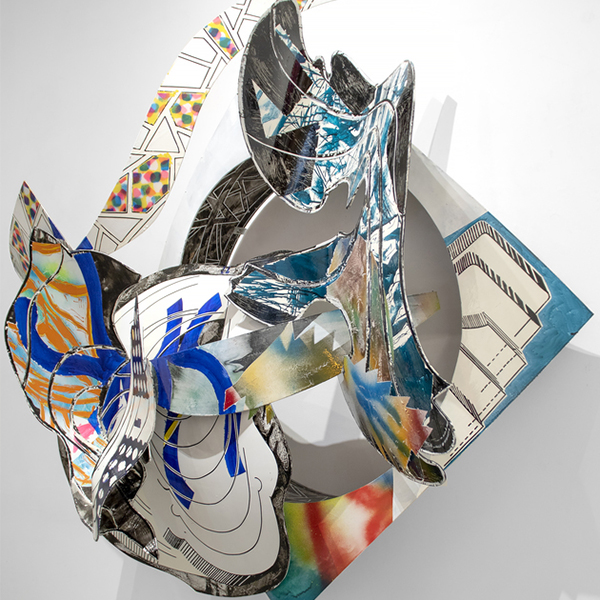

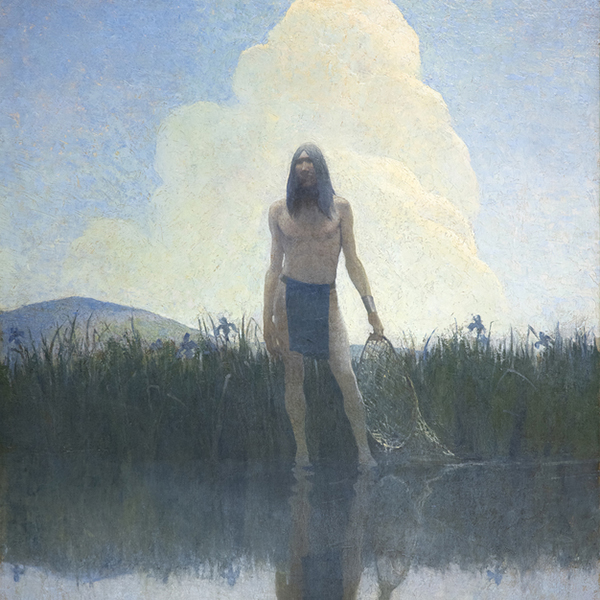

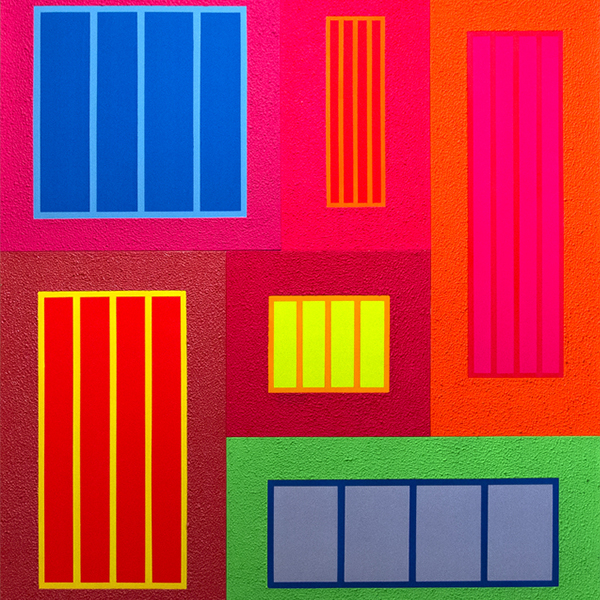

Bild-Galerie

Zusätzliche Ressourcen

Fragen Sie

Andere Werke von Tom Wesselmann

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

_tn28438.jpg )