EMIL NOLDE (1867-1956)

Provenienz

Joachim von Lepel, Neukirchen, 1958Privatsammlung, Deutschland

Sotheby's New York, Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale: Dienstag, 2. November 2010, Los 00021

Privatsammlung, New York

Literaturhinweise

Martin Urban, Emil Nolde, Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, Vol. Two, 1915-1951, London, 1990, Nr. 1250, abgebildet S. 511Geschichte

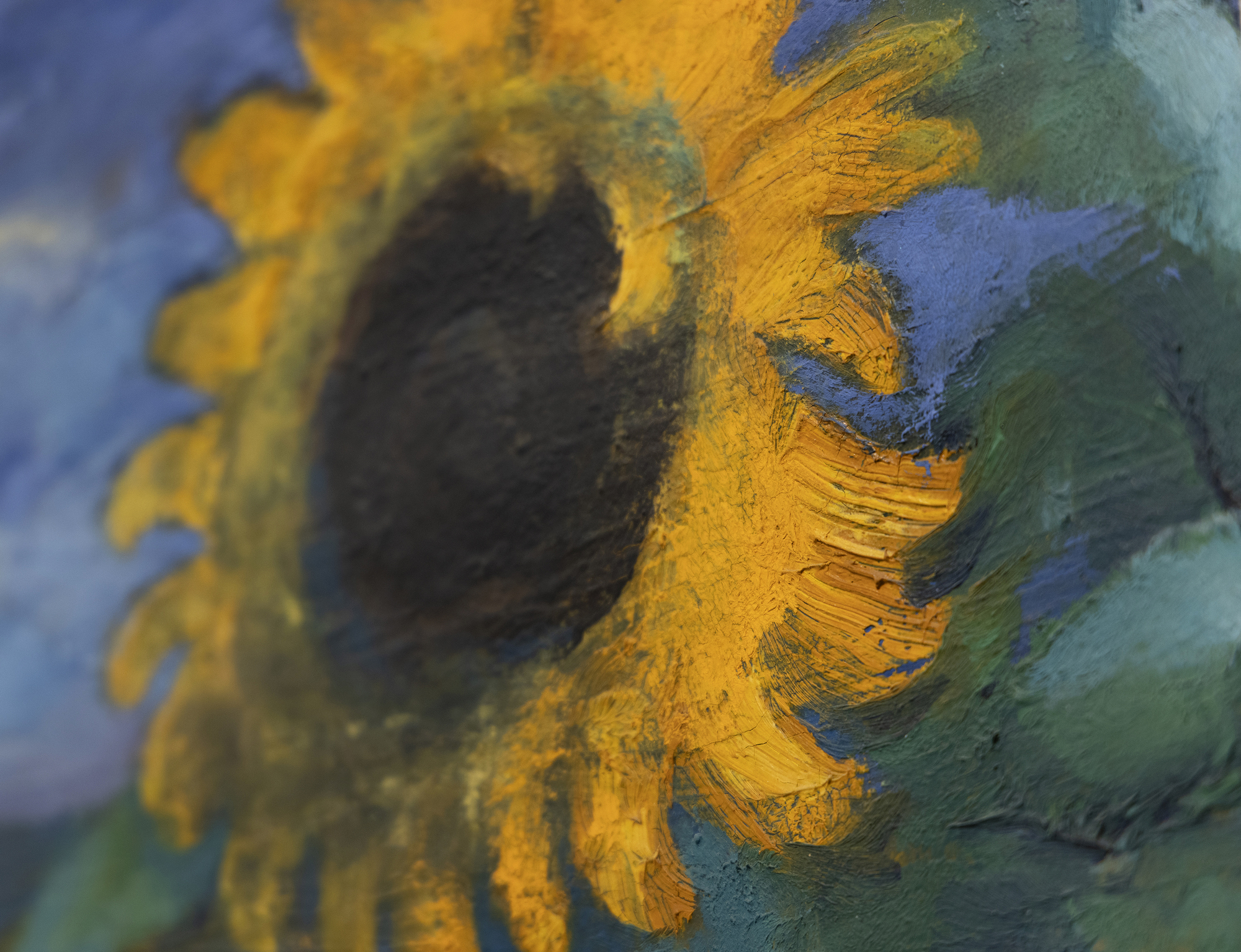

Der gelernte Holzschnitzer Emil Nolde war fast 30 Jahre alt, als er seine ersten Gemälde schuf. Die frühen Gemälde ähneln seinen Zeichnungen und Holzschnitten: groteske Figuren mit kühnen Linien und starken Kontrasten. Der Stil war neu und inspirierte die aufkommende Bewegung Die Brücke, deren Mitglieder Nolde 1906 einluden, sich ihnen anzuschließen. Doch erst als der Garten 1915 zu seiner Wirkungsstätte wurde, baute er auf seiner Beherrschung kontrastreicher Helligkeiten auf und konzentrierte sich auf die Farbe als oberstes Ausdrucksmittel. Später sagte Nolde: "Farbe ist Kraft, Kraft ist Leben", und er hätte nicht besser beschreiben können, warum seine Blumenbilder unsere Wahrnehmung von Farbe neu beleben.

Ein großer Teil der Stärke von Noldes dramatischem, wagnerianisch anmutendem Farbempfinden liegt in der Wirkung der Inszenierung von Primärfarben, wie den tiefen Rottönen und dem Goldgelb von Sonnenblumen, Abend II, vor einer düsteren Farbpalette. Der Kontrast unterstreicht und vertieft die Leuchtkraft der Blumen, nicht nur visuell, sondern auch emotional. Im Jahr 1937, als Noldes Kunst abgelehnt, beschlagnahmt und beschmutzt wurde, wurden seine Gemälde in ganz Nazi-Deutschland in schummrigen Galerien als "entartete Kunst" vorgeführt. Trotz dieser Behandlung verschaffte Noldes Status als "entarteter Künstler" seiner Kunst mehr Freiraum, da er die Gelegenheit nutzte, mehr als 1.300 Aquarelle zu schaffen, die er "unbemalte Bilder" nannte. Er war kein Neuling im Umgang mit dem Aquarell und zeichnete sich seit 1918 durch einen frei fließenden Malstil mit hoch aufgeladenen, transparenten Lavierungen aus. Sonnenblumen, Abend II, gemalt 1944, ist ein seltenes Ölbild aus der Kriegszeit. In diesem Werk ließ er seiner Fantasie freien Lauf, und seine Nass-in-Nass-Technik steigerte die Dramatik der einzelnen Blütenblätter.

Noldes intensive Beschäftigung mit Farben und Blumen, insbesondere Sonnenblumen, spiegelt seine anhaltende Verehrung für van Gogh wider. Er kannte van Gogh bereits seit 1899 und besuchte in den 1920er und frühen 1930er Jahren mehrere Ausstellungen mit Werken des niederländischen Künstlers. Sie teilten eine tiefe Liebe zur Natur. Noldes Hingabe an den Ausdruck und die symbolische Verwendung von Farbe fand in dem Motiv der Sonnenblume eine Fülle, und sie wurde für ihn wie für van Gogh zu einem persönlichen Symbol.

MARKTEINBLICKE

- Vollständig realisierte Sonnenblumengemälde sind nur selten erhältlich, und die meisten Werke zu diesem Thema befinden sich in Museumseinrichtungen.

- Die Blumenbilder, die auf Auktionen angeboten werden, gehören zu den meistverkauften Werken Noldes.

- Wie die Grafik von Art Market Research zeigt, hat der Markt für Emile Nolde seit 1976 um 648,1 % zugelegt.

Spitzenergebnisse bei Auktionen

"Herbstmeer XVI" (1911) wurde für 7.344.500 Dollar verkauft.

Die "Indische Tänzerin" (1917) wurde für 5.262.500 Dollar verkauft.

"Rotblondes Mädchen" (1919) wurde für 3.826.851 Dollar verkauft.

"Sonnenuntergang" (1909) wurde für 3.517.759 Dollar verkauft.

Vergleichbare Gemälde bei einer Auktion verkauft

"Meer I" (1947) wurde für 3.132.800 Dollar verkauft.

- Gemalt drei Jahre nach Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Geringfügig kleiner als Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Meer I ist kein Blumenbild, sondern eine Meereslandschaft, ein weiteres Thema, das Nolde in dieser Zeit häufig überarbeitete

"Kleine Sonnenblumen" (1946) wurde für 3.042.500 Dollar verkauft.

- Gemalt zwei Jahre nach Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Geringfügig kleiner als Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Enthält auch ein Sonnenblumenmotiv

- Dieses Gemälde war 2014 Teil der Nolde-Retrospektive im Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Dänemark.

"Üppiger Garten" (1945) wurde für 2.658.500 Dollar verkauft.

- Gemalt ein Jahr nach Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Geringfügig größer als Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Auch wenn es sich nicht um eine Darstellung von Sonnenblumen handelt, ist der Üppige Garten eine ähnliche, eng geschnittene Blumenlandschaft.

"Grosse Sonnenblume und Clematis" (1943) wurde für 2.179.094 Dollar verkauft.

- Gemalt ein Jahr vor Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Geringfügig kleiner als Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Gleiches Thema Sonnenblumen