Frida Kahlo (1907 – 1954) is known for creating striking self-portraits that reflect her cultural identity and turbulent personal life. Her dramatic life story and the iconic self-portraits she painted have been endlessly reproduced and inspired a steady stream of scholarship, museum exhibitions, and record auction prices. Born in Coyoacan, Mexico City, Kahlo contracted polio at six years old, which left her with a permanent limp. Nonetheless, Kahlo became a promising pre-medical student before a near-fatal Trolley accident at age 18. During her long recovery, Kahlo taught herself to paint, developing a meticulous style and refocusing her ambition on becoming a professional artist.

Frida Kahlo (1907 – 1954) is known for creating striking self-portraits that reflect her cultural identity and turbulent personal life. Her dramatic life story and the iconic self-portraits she painted have been endlessly reproduced and inspired a steady stream of scholarship, museum exhibitions, and record auction prices. Born in Coyoacan, Mexico City, Kahlo contracted polio at six years old, which left her with a permanent limp. Nonetheless, Kahlo became a promising pre-medical student before a near-fatal Trolley accident at age 18. During her long recovery, Kahlo taught herself to paint, developing a meticulous style and refocusing her ambition on becoming a professional artist.

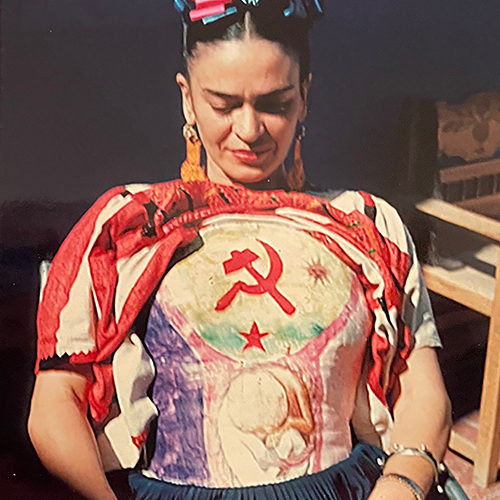

Throughout her artistic career, Kahlo’s favorite subject was herself. In her many self-portraits she explored issues of identity and self, probing the most sensitive and emotionally intense areas of her life, such as her medical conditions and turbulent marriage to fellow artist Diego Rivera. Kahlo was also deeply supportive of the Mexican Revolution, which concluded around 1920. In the wake of the Revolution, artists such as the Mexican Muralists created large scale public paintings that celebrating Mexican identity and heritage as a way to reunify the nation. Although she kept her personal subject matter, Kahlo also reflected this nationalistic spirit by incorporating indigenous and folk aspects of Mexican culture into her work.

In the late 1930s, Kahlo’s work began to earn an international reputation. In 1938, she had her first solo show at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York followed shortly by another in Paris, after which the Louvre purchased one of her self-portraits, its first acquisition by a 20th century Mexican artist. Although her artistic career was cut short by an early death in 1953, Kahlo’s reputation and success have grown tremendously, and her work has become known internationally for its uncompromising exploration of the self.

Kahlo has been the subject of several retrospective exhibitions, including Frida Kahlo. Paintings and drawings from Mexico’s collections, Faberge Museum, St. Petersburg, 2016; Frida Kahlo, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2008; Frida Kahlo, Tate Modern, London, 2005; and The World of Frida Kahlo, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, 1993. Kahlo’s work is represented in the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco; The Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC.