EMIL NOLDE (1867-1956)

Procedencia

Joachim von Lepel, Neukirchen, 1958Colección privada, Alemania

Sotheby's Nueva York, venta nocturna de arte moderno e impresionista: Martes, 2 de noviembre de 2010, Lote 00021

Colección privada, Nueva York

Literatura

Martin Urban, Emil Nolde, Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, Vol. Two, 1915-1951, Londres, 1990, nº 1250, ilustrado en la página 511Historia

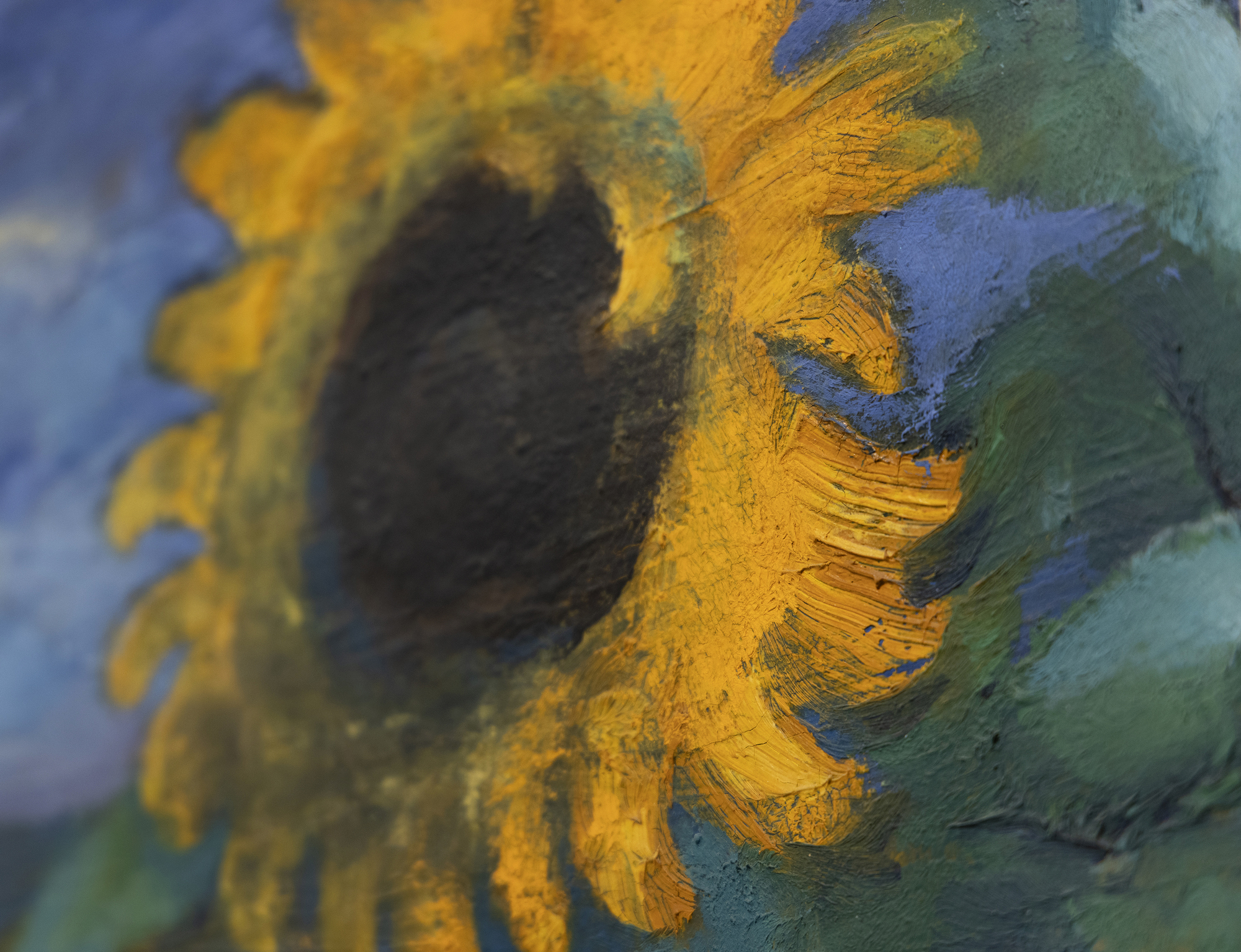

Formado como escultor en madera, Emil Nolde tenía casi 30 años antes de realizar sus primeros cuadros. Los primeros cuadros se parecían a sus dibujos y grabados en madera: figuras grotescas con líneas atrevidas y fuertes contrastes. El estilo era nuevo e inspiró al naciente movimiento Die Brücke (El Puente), cuyos miembros invitaron a Nolde a unirse a ellos en 1906. Pero no fue hasta que el jardín se convirtió en su locus operandi, en 1915, cuando aprovechó su dominio de los contrastes de luminosidad para centrarse en el color como medio supremo de expresión. Más tarde, Nolde afirmó que "el color es la fuerza, la fuerza es la vida", y no podría haber caracterizado mejor por qué sus pinturas de flores revigorizan nuestra percepción del color.

Gran parte de la fuerza de la sensibilidad cromática dramática y wagneriana de Nolde es el efecto de la puesta en escena de los colores primarios, como los rojos profundos y los amarillos dorados de Sonnenblumen, Abend II, frente a una paleta sombría. El contraste resalta y profundiza la luminosidad de las flores, no sólo visualmente, sino también emocionalmente. En 1937, cuando el arte de Nolde fue rechazado, confiscado y profanado, sus cuadros desfilaron como "arte degenerado" por toda la Alemania nazi en galerías poco iluminadas. A pesar de ese trato, la condición de artista degenerado de Nolde dio a su arte más espacio para respirar porque aprovechó la oportunidad para producir más de 1.300 acuarelas, que él llamaba "cuadros sin pintar". Sin ser un novato en el manejo de la acuarela, su estilo de pintura de flujo libre se caracterizaba desde 1918 por sus lavados transparentes de gran carga. Sonnenblumen, Abend II, pintado en 1944, es un raro óleo de tiempos de guerra. En esta obra dio rienda suelta a su imaginación, y la utilización de técnicas de mojado sobre mojado realzó el dramatismo de cada pétalo.

La intensa preocupación de Nolde por el color y las flores, especialmente los girasoles, refleja su continua devoción por Van Gogh. Conoció a Van Gogh ya en 1899 y, durante los años veinte y principios de los treinta, visitó varias exposiciones de la obra del artista holandés. Ambos compartían un profundo amor por la naturaleza. La dedicación de Nolde a la expresión y al uso simbólico del color encontró su plenitud en el tema del girasol, y se convirtió en un símbolo personal para él, como lo fue para Van Gogh.

CONOCIMIENTOS DEL MERCADO

- Los cuadros de girasoles completamente realizados rara vez están disponibles, y la mayoría de las obras de este tema se encuentran en instituciones museísticas.

- Cuando los cuadros de flores han salido a subasta, han sido algunas de las obras más vendidas de Nolde.

- Como ilustra el gráfico de Art Market Research, el mercado de Emile Nolde se ha revalorizado un 648,1% desde 1976.

Los mejores resultados en la subasta

"Herbstmeer XVI" (1911) se vendió por 7.344.500 dólares.

"Indische Tänzerin" (1917) se vendió por 5.262.500 dólares.

"Rotblondes Mädchen" (1919) se vendió por 3.826.851 dólares.

"Sonnenuntergang" (1909) se vendió por 3.517.759 dólares.

Cuadros comparables vendidos en subasta

"Meer I" (1947) se vendió por 3.132.800 dólares.

- Pintado tres años después de Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Un poco más pequeño que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- En lugar de flores, Meer I es un paisaje marino, otro tema que Nolde revisó con frecuencia durante este periodo

"Kleine Sonnenblumen" (1946) se vendió por 3.042.500 dólares.

- Pintado dos años después de Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Un poco más pequeño que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- También presenta un tema de girasoles

- Este cuadro fue incluido en la retrospectiva de Nolde de 2014 en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Luisiana, Dinamarca

"Üppiger Garten" (1945) se vendió por 2.658.500 dólares.

- Pintado un año después de Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Ligeramente más grande que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Aunque no se trata de una representación de girasoles, el Üppiger Garten es un paisaje floral similar, muy recortado

"Grosse Sonnenblume und Clematis" (1943) se vendió por 2.179.094 dólares.

- Pintado un año antes de Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Un poco más pequeño que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- El mismo tema del girasol