GEORGIA O'KEEFFE (1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

Procedencia

Un lugar americano, Nueva YorkSr. y Sra. Max Ascoli, Nueva York, 1944

Descendientes en familia

Harold Diamond, Nueva York, c. 1975

Galería Gerald Peters, Santa Fe, Nuevo México

Galería Elaine Horwich, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1978

Colección del Sr. y la Sra. E. Parry Thomas, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1978

Colección privada, Estados Unidos

Exposición

Nueva York, Nueva York, An American Place, Georgia O'Keeffe, Pinturas - 1943, 11 de enero - 11 de marzo de 1944, nº 8West Palm Beach, Florida, Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens, Discoveri...Más....ng Creatividad: American Art Masters, del 10 de enero al 17 de marzo de 2024

Literatura

Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Catalogue Raisonné Volume Two (New Haven y Londres: Yale University Press, 1999), cat. nº 1066, p. 670....MENOS....

Historia

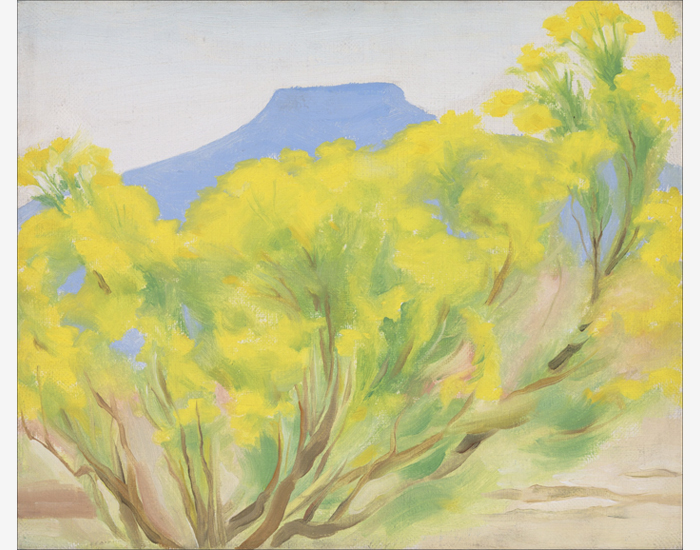

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), New Mexico (1943), de la célebre artista estadounidense Georgia O'Keeffe, es un ejemplo del estilo más aéreo y naturalista que le inspiró el desierto. O'Keeffe tenía una gran afinidad con la belleza distintiva del suroeste, y estableció allí su hogar entre los árboles enjutos, las vistas dramáticas y los cráneos de animales blanqueados que pintó con tanta frecuencia. O'Keeffe fijó su residencia en el Ghost Ranch, un rancho de amigos situado a doce millas del pueblo de Abiquiú, en el norte de Nuevo México, y allí pintó este álamo. El estilo más suave, acorde con este tema, se aleja de sus atrevidos paisajes arquitectónicos y de sus flores de colores.

El álamo se abstrae en suaves manchas de verde a través de las cuales se ven ramas más delineadas, que se mueven en espiral en el espacio contra bolsas de cielo azul. El modelado del tronco y la delicada energía de las hojas son una continuación de los experimentos realizados con los árboles regionales del noreste que habían cautivado a O'Keeffe años antes: arces, castaños, cedros y álamos, entre otros. Dos dramáticos lienzos de 1924, Árboles de otoño, El arce y El castaño gris, son ejemplos tempranos de centralidad lírica y resuelta, respectivamente. Como se ve en estos primeros cuadros de árboles, O'Keeffe exageró la sensibilidad de su tema con el color y la forma.

MásCONOCIMIENTOS DEL MERCADO

-

El gráfico de Art Market Research muestra que, desde 1976, los cuadros de O'Keeffe han aumentado a una tasa de rendimiento anual del 11,6%.

-

Desde la venta que marcó un récord en 2014(Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, vendida por más de 44,4 millones de dólares), el mercado de Georgia O'Keeffe ha visto una demanda cada vez mayor de óleos de autor.

-

Incluso cuando el mercado de O'Keeffe sufrió un ligero descenso durante la pandemia de 2020 (como se ve en el gráfico de AMR), el índice global de volumen de ventas en subasta de ArtPrice muestra que O'Keeffe pasó del puesto 263 al 63 de los artistas más vendidos ese año, lo que ilustra que los cuadros de O'Keeffe siguen siendo cada vez más demandados, sobre todo si se comparan con el rendimiento de otros artistas durante ese mismo periodo.

Los mejores resultados en la subasta

"Jimson weed/ White flower no. 1" (1932) se vendió por 44.405.000 dólares.

"Rosa blanca con espuela de caballero nº I" (1927) se vendió por 26.725.000 dólares.

"Autumn Leaf II" (1927) se vendió por 15.275.000 dólares.

"Calle A" (1926) se vendió por 13.285.500 dólares.

Cuadros comparables vendidos en subasta

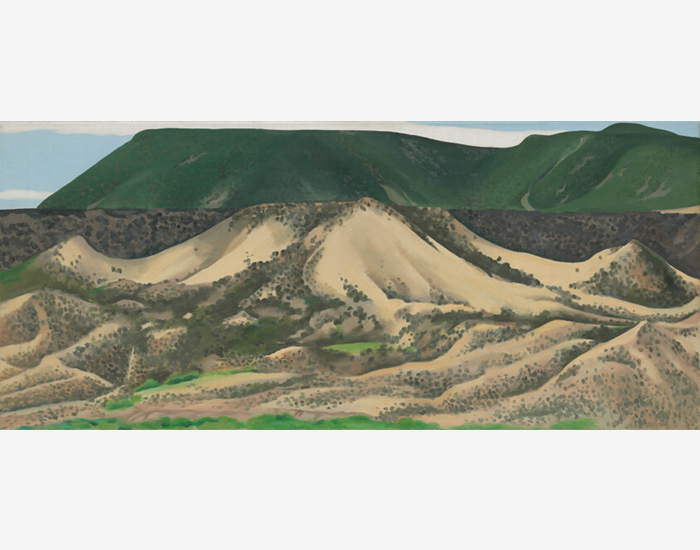

"Colinas rojas con pedernal, nubes blancas" (1936) se vendió por 12.298.000 dólares.

- Una vista más amplia del paisaje del desierto, este cuadro se vendió en la subasta de la colección del cofundador de Microsoft Paul Allen

- La naturaleza era a menudo el tema del arte de O'Keeffe, y algunos álamos se pueden ver en la distancia de este paisaje

"Lago George con abedul blanco" (1921) se vendió por 11.292.000 dólares.

- Este lienzo temprano con un tema similar, aunque de menor escala, se vendió por más de 11,2 millones de dólares en 2018, el tercer precio más alto en una subasta para O'Keeffe

- Los temas relacionados con la naturaleza, en particular los árboles, fueron un tema frecuente para O'Keeffe

"Cerca de Abiquiu, Nuevo México" (1931) se vendió por 8.412.500 dólares.

- Una obra más pequeña que Cottonwood Tree (cerca de Abiquiu), Nuevo México

- Un paisaje anterior de la misma zona en Nuevo México, esta pieza se vendió por más de 8,4 millones de dólares en 2018

"The Red Maple at Lake George" (1926) se vendió por 8.187.500 dólares.

- Este tema de naturaleza de O'Keeffe del mismo tamaño se vendió en 2018 por más de 8,18 millones de dólares

- Ejemplo anterior de 1926

"Formas de la naturaleza - Gaspé" (1931) se vendió por 6.870.200 dólares.

- Tema de naturaleza abstracta a pequeña escala

- Vendido recientemente por más de 6,87 millones de dólares

SCARCITY

-

El 43% de los cuadros de O'Keeffe se encuentran ya en colecciones de museos.

-

De los 716 óleos sobre lienzo que pintó O'Keeffe, quedan menos de 300 disponibles para colecciones privadas.

-

Con el paso del tiempo, muchos de los cuadros de O'Keeffe que actualmente se encuentran en colecciones privadas serán legados a museos, por lo que muy pocos llegarán a estar disponibles.

- O'Keeffe pintó por primera vez los álamos en Abiquiu durante dos únicos años, de 1943 a 1945, y sólo creó un pequeño puñado de cuadros para esta serie principal. Muchas obras de esta serie de álamos se encuentran ahora en museos como el Butler Institute of American Art y el Brooklyn Museum.

Pinturas de álamos, árboles y Abiquiu en colecciones de museos

Museo Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Museo de Arte de Santa Bárbara

Museo Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Instituto Butler de Arte Americano, Ohio

Museo Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Museo de Arte de Cleveland

Museo de Arte de Dallas

Museo de Arte de Nuevo México, Santa Fe

Museo de Bellas Artes de Boston

Museo de Brooklyn, Nueva York

Museo Metropolitano de Arte, Nueva York

Museo Whitney de Arte Americano, Nueva York

Museo Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Museo de Arte de Cleveland

Instituto de Arte de Chicago

Galería de imágenes

Recursos adicionales

Autenticación

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), Nuevo México, 1943 figura con el número 1066 en el catálogo razonado de obras de arte de Georgia O'Keeffe de Barbara Buhler Lynes. El cuadro se ilustra en la página 670 del segundo volumen.

Véase el catálogo razonado

Preguntar

También le puede gustar