ALEXANDER CALDER-nbsp(1898-1976)

Provenance

Galerie Perls, New YorkCollection privée, acquise auprès des personnes susmentionnées

Exposition

Crane Gallery, Londres, Calder : Huiles, Gouaches, Mobiles et Tapisseries, 5 mars-1er mai 1992Histoire

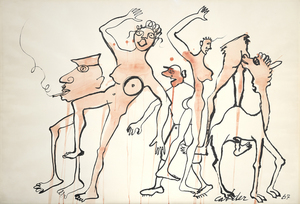

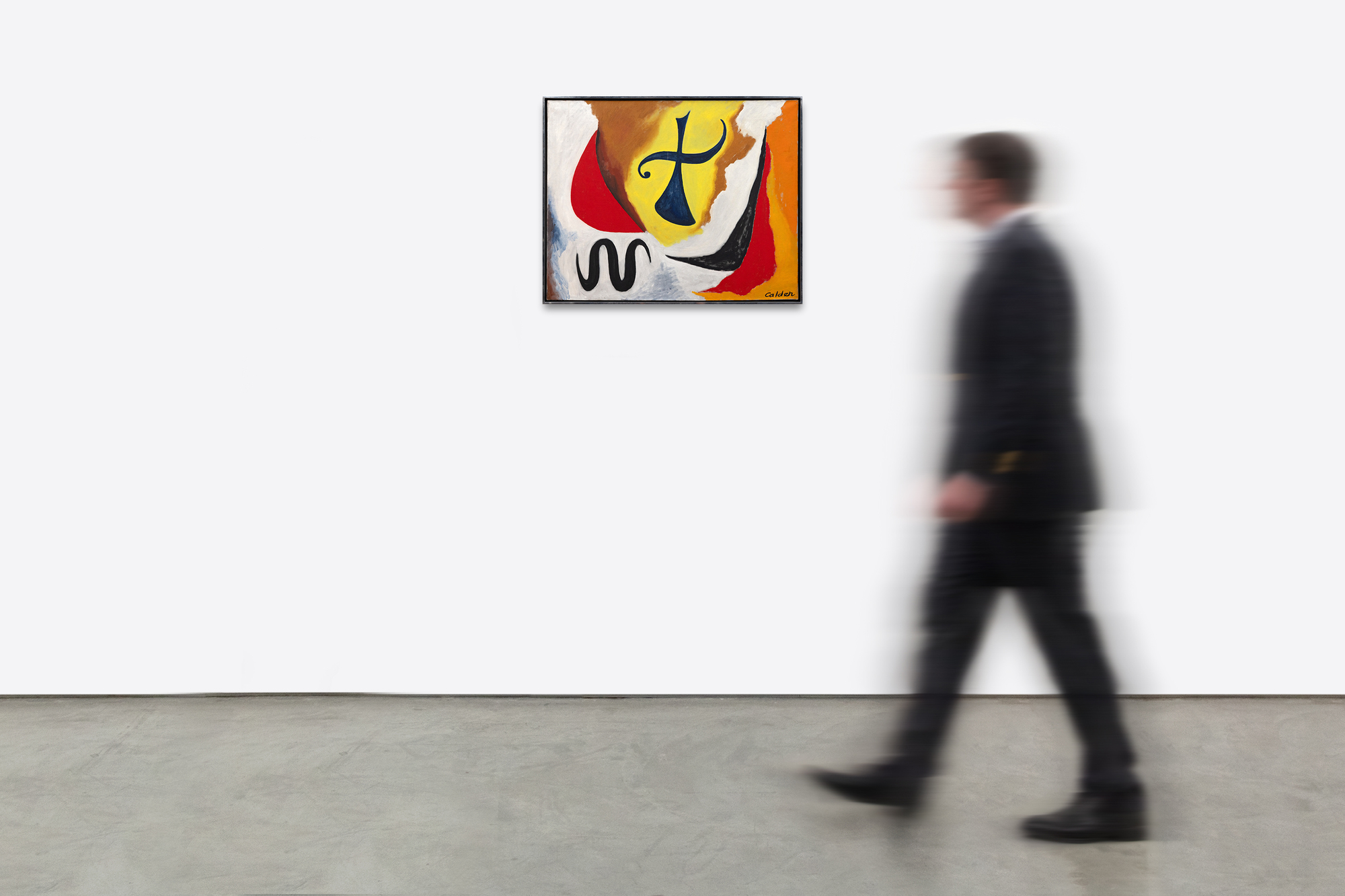

Alexander Calder a exécuté un nombre surprenant de peintures à l'huile au cours de la seconde moitié des années 1940 et au début des années 1950. À cette époque, le choc de sa visite en 1930 dans l'atelier de Mondrian, où il avait été impressionné non par les peintures mais par l'environnement, s'était transformé en un langage artistique propre à Calder. Ainsi, alors que Calder peint La Croix en 1948, il est déjà sur le point d'obtenir une reconnaissance internationale et de remporter le grand prix de sculpture de la XX VIe Biennale de Venise en 1952. Travaillant sur ses peintures de concert avec sa pratique de la sculpture, Calder aborde les deux médiums avec le même langage formel et la même maîtrise de la forme et de la couleur.

Calder était profondément intrigué par les forces invisibles qui maintiennent les objets en mouvement. Transposant cet intérêt de la sculpture à la toile, nous constatons que Calder a créé une sensation de couple dans La Croix en déplaçant ses plans et son équilibre. À l'aide de ces éléments, il a créé un mouvement implicite suggérant que la figure pousse vers l'avant ou même qu'elle descend des cieux. L'élan déterminé de La Croixest encore amplifié par des détails tels que les bras tendus du sujet, le vecteur courbe en forme de poing sur la gauche et la silhouette serpentine.

Calder adopte également un fort fil d'abandon poétique sur toute la surface de La Croix. Cela fait écho au langage visuel hiératique et nettement personnel de son bon ami Miró, mais c'est tout Calder dans l'animation efficace des différents éléments de ce tableau. Aucun artiste n'a gagné plus de licence poétique que Calder, et tout au long de sa carrière, l'artiste est resté convivialement flexible dans sa compréhension de la forme et de la composition. Il a même accueilli favorablement les myriades d'interprétations des autres, écrivant en 1951 : "Que d'autres saisissent ce que j'ai à l'esprit ne semble pas essentiel, du moins tant qu'ils ont autre chose dans le leur."

Quoi qu'il en soit, il est important de se rappeler que La Croix a été peinte peu après les bouleversements de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et que, pour certains, elle apparaît comme un reflet sobre de l'époque. Par-dessus tout, La Croix prouve qu'Alexander Calder a d'abord pris son pinceau pour élaborer des idées sur la forme, la structure, les relations dans l'espace et, surtout, le mouvement.

LES CONNAISSANCES DU MARCHÉ

- Le graphique d'Art Market Research montre que depuis janvier 1976, la valeur des œuvres de Calder a augmenté de 5068,8%. Sur cette même période de huit ans, le taux de rendement annuel des œuvres de Calder a été de 8,7 %.

- Dans le deuxième graphique, on voit que la valeur des œuvres de Calder a augmenté de 66 % depuis novembre 2014, ce qui apporte un taux de rendement annuel de 6,3 %.

- Si Calder était un artiste prolifique, les peintures à l'huile sur toile comme La Croix comptent parmi les exemples les plus rares de l'œuvre de l'artiste.

Tableaux comparables vendus aux enchères

"Personnage" (1946) vendu pour 1 865 000 USD.

- Peint deux ans avant La Croix

- Couleurs similaires, mais l'abstraction dans The Cross est plus réaliste.

- Vendue aux enchères en 2014, cette peinture vaudrait bien plus de 3 millions de dollars aujourd'hui.

"Fond rouge" (1949) vendu pour 1 815 000 USD.

- Peint juste un an après La Croix

- Une belle abstraction, mais une composition moins intéressante que celle de La Croix.

- Le fond ici n'est qu'une seule couleur, tandis que la Croix équilibre plusieurs teintes dans son fond.