EMIL NOLDE (1867-1956)

Provenance

Joachim von Lepel, Neukirchen, 1958Collection privée, Allemagne

Sotheby's New York, Vente du soir d'art impressionniste et moderne : Mardi 2 novembre 2010, Lot 00021

Collection privée, New York

Littérature

Martin Urban, Emil Nolde, Catalogue raisonné des peintures à l'huile, vol. 2, 1915-1951, Londres, 1990, n° 1250, illustré p. 511.Histoire

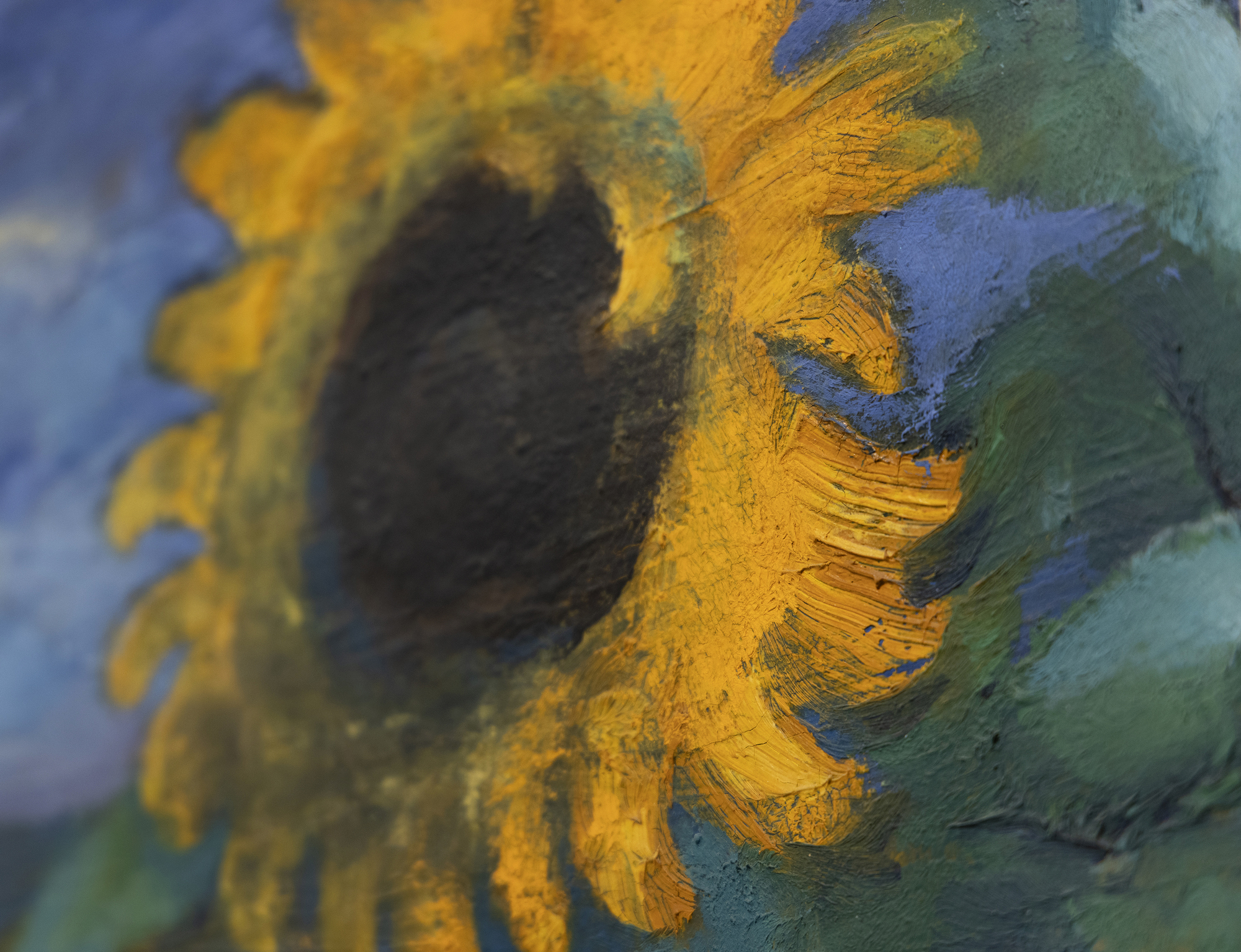

Sculpteur sur bois de formation, Emil Nolde avait presque 30 ans lorsqu'il a réalisé ses premières peintures. Les premières peintures ressemblent à ses dessins et à ses gravures sur bois : des figures grotesques aux lignes audacieuses et aux contrastes forts. Le style était nouveau et a inspiré le mouvement naissant Die Brücke (Le Pont), dont les membres ont invité Nolde à se joindre à eux en 1906. Mais ce n'est qu'en 1915, lorsque le jardin devient son lieu d'action, qu'il s'appuie sur sa maîtrise des contrastes de luminosité pour se concentrer sur la couleur comme moyen d'expression suprême. Plus tard, Nolde a affirmé que "la couleur est la force, la force est la vie", et il n'aurait pas pu mieux définir la raison pour laquelle ses peintures de fleurs revigorent notre perception de la couleur.

La force de la sensibilité aux couleurs de Nolde, dramatique et wagnérienne, réside en grande partie dans l'effet de la mise en scène des couleurs primaires, comme les rouges profonds et les jaunes dorés de Sonnenblumen, Abend II, sur une palette sombre. Le contraste fait ressortir et approfondit la luminosité des fleurs, non seulement sur le plan visuel, mais aussi sur le plan émotionnel. En 1937, lorsque l'art de Nolde a été rejeté, confisqué et souillé, ses tableaux ont été présentés comme de "l'art dégénéré" dans toute l'Allemagne nazie, dans des galeries mal éclairées. Malgré ce traitement, le statut d'artiste dégénéré de Nolde a permis à son art de respirer davantage, car il a saisi l'occasion de produire plus de 1 300 aquarelles, qu'il appelait "tableaux non peints". N'étant pas un novice dans le maniement de l'aquarelle, son style libre se caractérisait depuis 1918 par des lavis transparents et très chargés. Sonnenblumen, Abend II, peint en 1944, est une huile rare datant de la guerre. Il a laissé libre cours à son imagination dans cette œuvre, et son utilisation de la technique "mouillé sur mouillé" a renforcé le caractère dramatique de chaque pétale.

L'intense préoccupation de Nolde pour la couleur et les fleurs, en particulier les tournesols, reflète son attachement constant à van Gogh. Il connaissait van Gogh dès 1899 et, dans les années 1920 et au début des années 1930, il a visité plusieurs expositions de l'artiste néerlandais. Ils partageaient un amour profond de la nature. Le dévouement de Nolde à l'expression et à l'utilisation symbolique de la couleur a trouvé sa plénitude dans le sujet du tournesol, qui est devenu un symbole personnel pour lui, comme pour Van Gogh.

LES CONNAISSANCES DU MARCHÉ

- Les peintures de tournesols entièrement réalisées sont rarement disponibles, et la plupart des œuvres de ce sujet se trouvent dans des institutions muséales.

- Lorsque des peintures de fleurs ont été mises aux enchères, elles ont fait partie des œuvres les plus vendues de Nolde.

- Comme l'illustre le graphique de Art Market Research, le marché d'Emile Nolde s'est apprécié de 648,1% depuis 1976.

Les meilleurs résultats aux enchères

"Herbstmeer XVI" (1911) a été vendu pour 7 344 500 dollars.

"Indische Tänzerin" (1917) vendu pour 5 262 500 $.

"Rotblondes Mädchen" (1919) a été vendu pour 3 826 851 dollars.

"Sonnenuntergang" (1909) a été vendu pour 3 517 759 $.

Tableaux comparables vendus aux enchères

"Meer I" (1947) a été vendu pour 3 132 800 dollars.

- Peint trois ans après Sonnenblumen, Abend II.

- Légèrement plus petit que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Plutôt que des fleurs, Meer I est un paysage marin, un autre sujet que Nolde a fréquemment révisé au cours de cette période.

"Kleine Sonnenblumen" (1946) a été vendu pour 3 042 500 dollars.

- Peint deux ans après Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Légèrement plus petit que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Présente également un sujet tournesol

- Cette peinture a été incluse dans la rétrospective Nolde de 2014 au musée d'art moderne de Louisiane, au Danemark.

"Üppiger Garten" (1945) a été vendu pour 2 658 500 dollars.

- Peint un an après Sonnenblumen, Abend II.

- Légèrement plus grand que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Bien qu'il ne s'agisse pas d'une représentation de tournesols, Üppiger Garten est un paysage floral similaire, au cadrage serré.

"Grosse Sonnenblume und Clematis" (1943) a été vendu pour 2 179 094 $.

- Peint un an avant Sonnenblumen, Abend II.

- Légèrement plus petit que Sonnenblumen, Abend II

- Même sujet de tournesol