GEORGIA O'KEEFFE (1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

Provenance

Un lieu américain, New YorkM. et Mme Max Ascoli, New York, 1944

Descendu dans la famille

Harold Diamond, New York, vers 1975

Galerie Gerald Peters, Santa Fe, Nouveau-Mexique

Galerie Elaine Horwich, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1978

Collection de M. et Mme E. Parry Thomas, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1978

Collection privée, États-Unis

Exposition

New York, New York, An American Place, Georgia O'Keeffe, Paintings - 1943, 11 janvier - 11 mars 1944, n° 8West Palm Beach, Floride, Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens, Discoveri...Plus.....ng Creativity : Les maîtres de l'art américain, du 10 janvier au 17 mars 2024

Littérature

Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Catalogue Raisonné Volume Two (New Haven et Londres : Yale University Press, 1999), cat. no 1066, p. 670....MOINS.....

Histoire

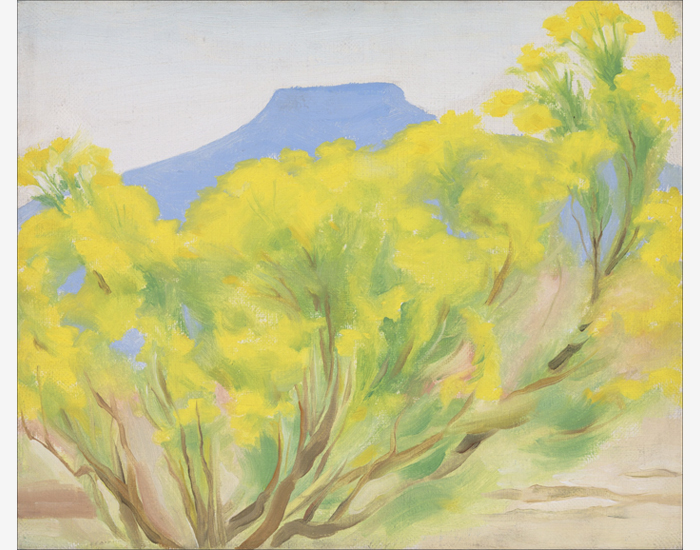

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), New Mexico (1943) de la célèbre artiste américaine Georgia O'Keeffe est exemplaire du style plus aéré et naturaliste que le désert lui a inspiré. O'Keeffe avait une grande affinité avec la beauté particulière du Sud-Ouest et y a élu domicile parmi les arbres touffus, les panoramas spectaculaires et les crânes d'animaux blanchis qu'elle a si souvent peints. O'Keeffe s'est installée à Ghost Ranch, un ranch pour dames situé à 30 km du village d'Abiquiú, au nord du Nouveau-Mexique, et a peint ce peuplier dans les environs. Le style plus doux qui convient à ce sujet s'écarte de ses paysages architecturaux audacieux et de ses fleurs aux tons de bijoux.

Le peuplier deltoïde est abstrait en de douces taches de verts verdoyants à travers lesquelles on aperçoit des branches plus délimitées, s'enroulant en spirale dans l'espace sur des poches de ciel bleu. Le modelage du tronc et l'énergie délicate des feuilles s'inscrivent dans la continuité des expérimentations passées avec les arbres régionaux du Nord-Est qui avaient captivé O'Keeffe des années auparavant : érables, châtaigniers, cèdres et peupliers, entre autres. Deux toiles spectaculaires de 1924, Autumn Trees, The Maple et The Chestnut Grey, sont les premiers exemples de centralité lyrique et résolue, respectivement. Comme on le voit dans ces premières peintures d'arbres, O'Keeffe a exagéré la sensibilité de son sujet par la couleur et la forme.

plus deLES CONNAISSANCES DU MARCHÉ

Selon le graphique préparé par Art Market Research, les prix du marché de Georgia O'Keeffe ont augmenté à un taux de rendement annuel composé de 12,7 % depuis 1976.

Le record de Georgia O'Keeffe aux enchères a été établi en 2014 avec la vente de Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 pour plus de 44,4 millions de dollars américains. Cela reste la somme la plus élevée payée pour une artiste féminine lors d'une vente aux enchères.

Même lorsque le marché d'O'Keeffe a connu une légère baisse pendant la pandémie de 2020 (comme le montre le graphique AMR), l'indice mondial de chiffre d'affaires des ventes aux enchères d'ArtPrice montre qu'O'Keeffe est passé du 263e au 63e rang des artistes les plus vendus cette année-là, ce qui montre que les peintures d'O'Keeffe restent de plus en plus demandées, surtout si on les compare aux performances d'autres artistes pendant la même période.

- En moyenne, au cours des 40 dernières années, seuls 4 tableaux d'O'Keeffe sont vendus aux enchères chaque année.

Les meilleurs résultats aux enchères

"Herbe à Jimson/ Fleur blanche no. 1" (1932) a été vendue pour 44 405 000 USD.

"White Rose with Larkspur No. I" (1927) a été vendue pour 26 725 000 USD.

Le "Black Iris VI" (1936) a été vendu pour 21 110 000 USD.

"Autumn Leaf II" (1927) a été vendu pour 15 275 000 USD.

Tableaux comparables vendus aux enchères

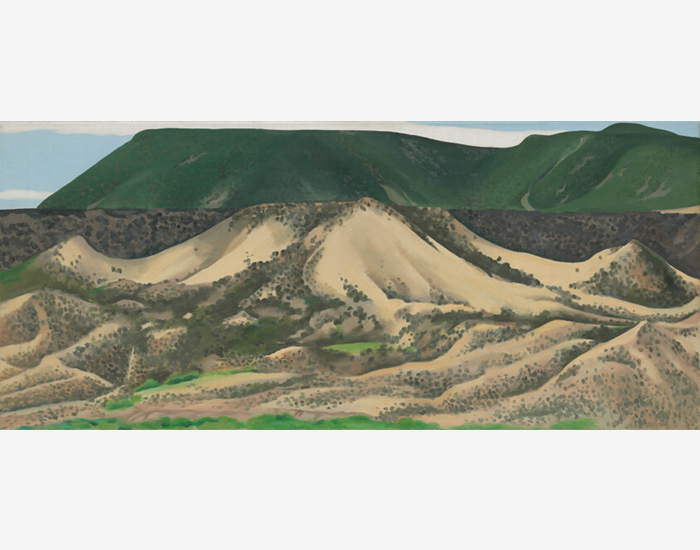

"Red Hills with Pedernal, White Clouds" (1936) a été vendu pour 12 298 000 $.

- Une vue plus large du paysage désertique, cette peinture a été vendue aux enchères de la collection du cofondateur de Microsoft, Paul Allen.

- La nature était souvent le sujet de l'art d'O'Keeffe, et on peut voir quelques peupliers de Virginie au loin dans ce paysage.

"Lake George With White Birch" (1921) a été vendu pour 11 292 000 dollars.

- Cette toile de jeunesse au sujet similaire, bien qu'à plus petite échelle, s'est vendue pour plus de 11,2 millions de dollars en 2018, le troisième prix le plus élevé pour O'Keeffe lors d'une vente aux enchères.

- Les sujets liés à la nature, en particulier les arbres, étaient souvent au centre des préoccupations de O'Keeffe.

"Near Abiquiu, New Mexico" (1931) vendu pour 8 412 500 $.

- Une œuvre plus petite que Cottonwood Tree (près d'Abiquiu), Nouveau-Mexique

- Un paysage antérieur de la même région du Nouveau-Mexique, cette pièce a été vendue pour plus de 8,4 millions de dollars en 2018.

"The Red Maple at Lake George" (1926) a été vendu pour 8 187 500 dollars.

- Ce sujet de nature O'Keeffe de la même taille a été vendu en 2018 pour plus de 8,18 millions de dollars.

- Exemple plus ancien datant de 1926

"Formes de la nature - Gaspé" (1931) a été vendu pour 6 870 200 $.

- Sujet de nature abstrait à petite échelle

- Vendu récemment pour plus de 6,87 millions de dollars

SCARCITY

- 43% des peintures de O'Keeffe sont déjà conservées dans des collections de musées.

- Sur les 616 huiles sur toile peintes par O'Keeffe, moins de 300 sont encore disponibles dans des collections privées.

- Au fil du temps, un grand nombre des tableaux d'O'Keeffe qui se trouvent actuellement dans des collections privées seront légués à des musées, ce qui fait que très peu d'entre eux seront disponibles un jour.

- O'Keeffe n'a peint les peupliers d'Abiquiu que pendant deux ans, de 1943 à 1945, et n'a réalisé que neuf tableaux pour cette série principale. Six d'entre elles sont conservées dans des collections permanentes de musées, et trois seulement se trouvent encore en mains privées.

- Les Cottonwood Trees d' O'Keeffe - de la série originale de 1943-1945 et des années suivantes - se trouvent dans les principales collections de musées, notamment le Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, le Butler Institute of American Art et le Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Peintures de peupliers, d'arbres et d'Abiquiu dans les collections des musées

Musée Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Musée d'art de Santa Barbara

Musée Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

L'Institut Butler d'art américain, Ohio

Musée Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Le musée d'art de Cleveland

Musée d'art de Dallas

Musée d'art du Nouveau-Mexique, Santa Fe

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Boston

Musée de Brooklyn, New York

Le Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Musée Georgia O'Keeffe, Santa Fe

Le musée d'art de Cleveland

Institut d'art de Chicago

Galerie d'images

Ressources supplémentaires

Authentification

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), New Mexico, 1943 est répertorié sous le numéro 1066 dans le catalogue raisonné des œuvres de Georgia O'Keeffe de Barbara Buhler Lynes. Le tableau est illustré à la page 670 du deuxième volume.

Voir le Catalogue Raisonné

demander

Vous pouvez également aimer