Perhaps no other question, made up of only three words, can confound an audience as well as this: What is art? The idea of an artist, as opposed to an artisan, is a recent convention and even newer still the notion of art for the sake of art. For centuries, art has carried utilitarian purposes – the murals of a Roman villa, the altarpiece of a church, the portrait painting.

In the 20th century new ideas of what could be counted as art emerged with the conception of the readymade. Coined by French Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, the readymade describes artwork made from already manufactured objects. Since his seminal Bicycle Wheel in 1913, a wheel mounted in a stool, artists have turned to already manufactured objects to create art. From Duchamp’s urinal to Tracey Emin’s unmade bed, the readymade has challenged our notions of what art is while providing layered meanings to the artwork.

With this in mind, we turn to Frida Kahlo’s corset. It is not merely an artifact of her life but a fully-fledged objet d’art. It is her personal cast which she transformed into a painted sculpture. She wore these plaster corsets as her spine was too weak to support itself due to the bus accident in which she was gravely injured at the age of nineteen. During her recovery, she picked up painting, her salvation from the pain and surgeries she would endure for the rest of her life. With an object this intimate and crucial, it is natural that she transformed them into expressions of herself. She covered this piece in her own beliefs and symbols, exploding with her vocabulary of color. Thus, the cast supported Kahlo, physically and metaphorically, as a vessel through which she could channel her voice.

Recent exhibitions such as Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up demonstrated that Kahlo’s clothing and outerwear were ways through which she could craft and exert her identity. Long before artists like Gilbert and George or Grayson Perry constructed their identity through clothing, Kahlo understood the power of her image. The corset has an added layer of power as she specifically painted it with symbols important to her including the politically potent hammer and sickle.

As fellow Mexican artist, Gabriel Orozco commented on his own readymade, “it was a combination between disappointment and amusement. Between surprise and skepticism.” There sits a tension between the viewer and the readymade. With Frida’s corset, the most compelling aspect of it as a readymade is that it surrounds a negative space that was once occupied by Kahlo. We are left to grapple with a practical item whose outline hints at the physical body of Frida Kahlo and through painting its surface, she has left her metaphorical spirit. In transforming a functional and necessary object, Kahlo joined a lineage of readymade artists.

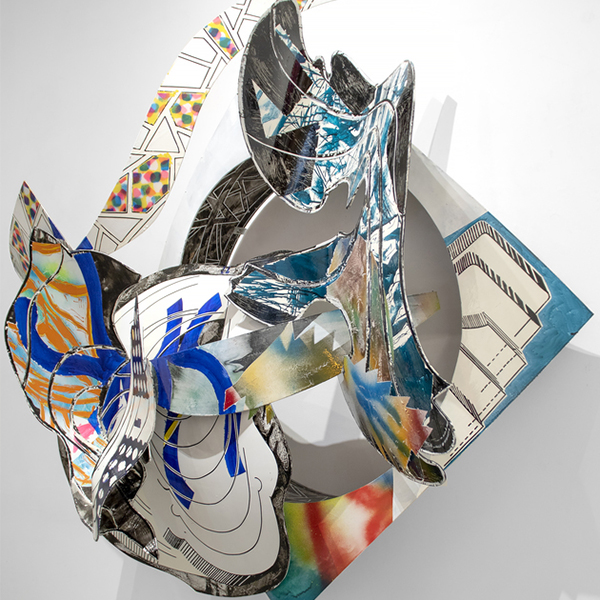

InquireImage Gallery

Art Detail

Please contact the gallery for more information.