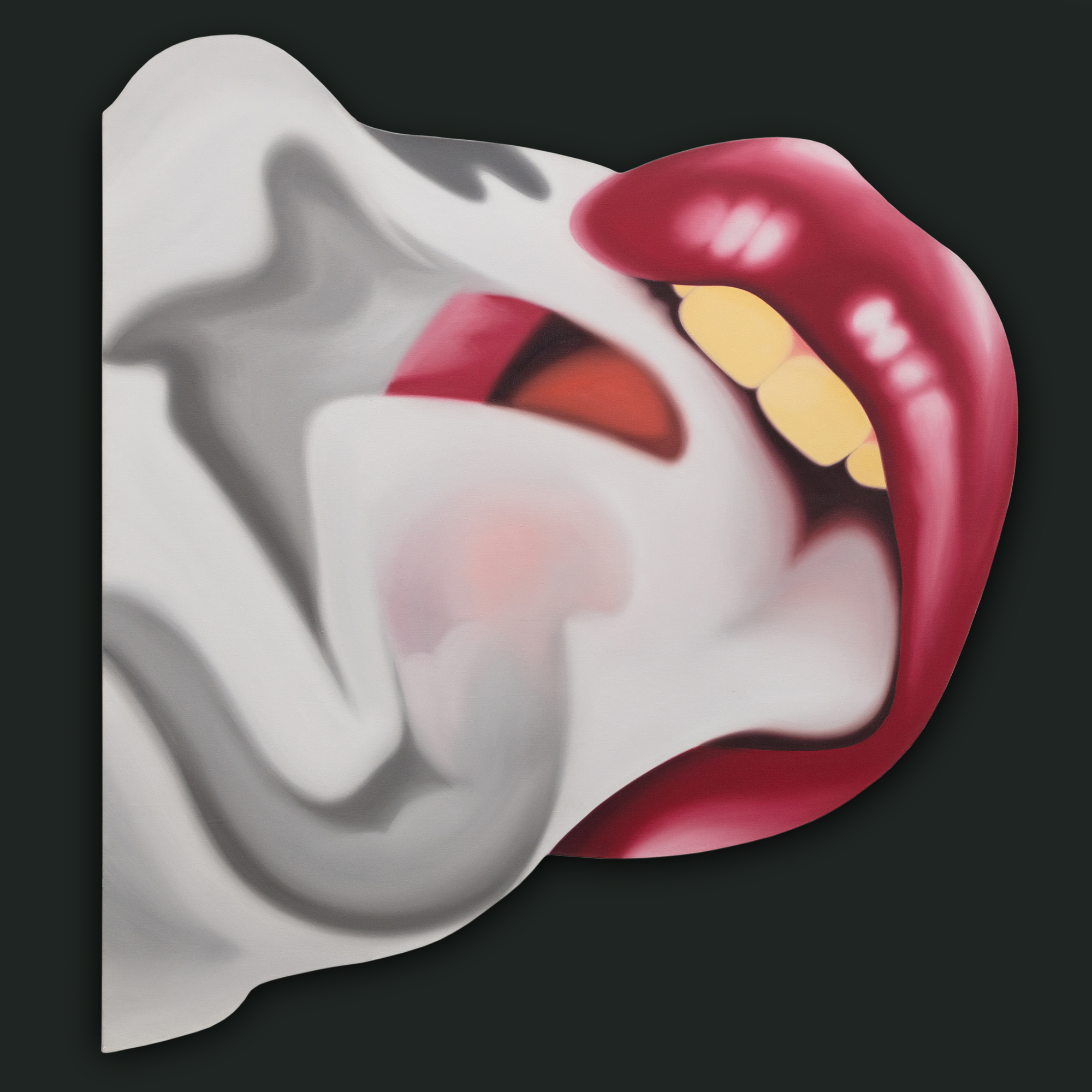

טום וסלמן(1931-2004)

מקור ומקור

עיזבון האמןגלריה רוברט מילר, ניו יורק

אוסף פרטי, יפן, נרכש מהנ"ל, 2006

אוסף פרטי של יוסאקו מאזאווה, יפן, נרכש מהנ"ל, 2012

סותבי'ס ניו יורק: מכירת ערב לאמנות עכשווית, 18 במאי 2017, פריט 28

אוסף פרטי, שנרכש מהמכירה הנ"ל

כריסטי'ס לונדון: מכירת ערב המאה ה-20/21, יום שלישי, 28 ביוני 2022, פריט 73

הת'ר ג'יימס פיין ארט

אוסף פרטי, שנרכש מהנ"ל

תערוכה

ניו יורק, גלריה סידני ג'ניס, ציור חדש... עוד...מאת תום וסלמן, אפריל-מאי 1976, מס' 9... פחות...

היסטוריה

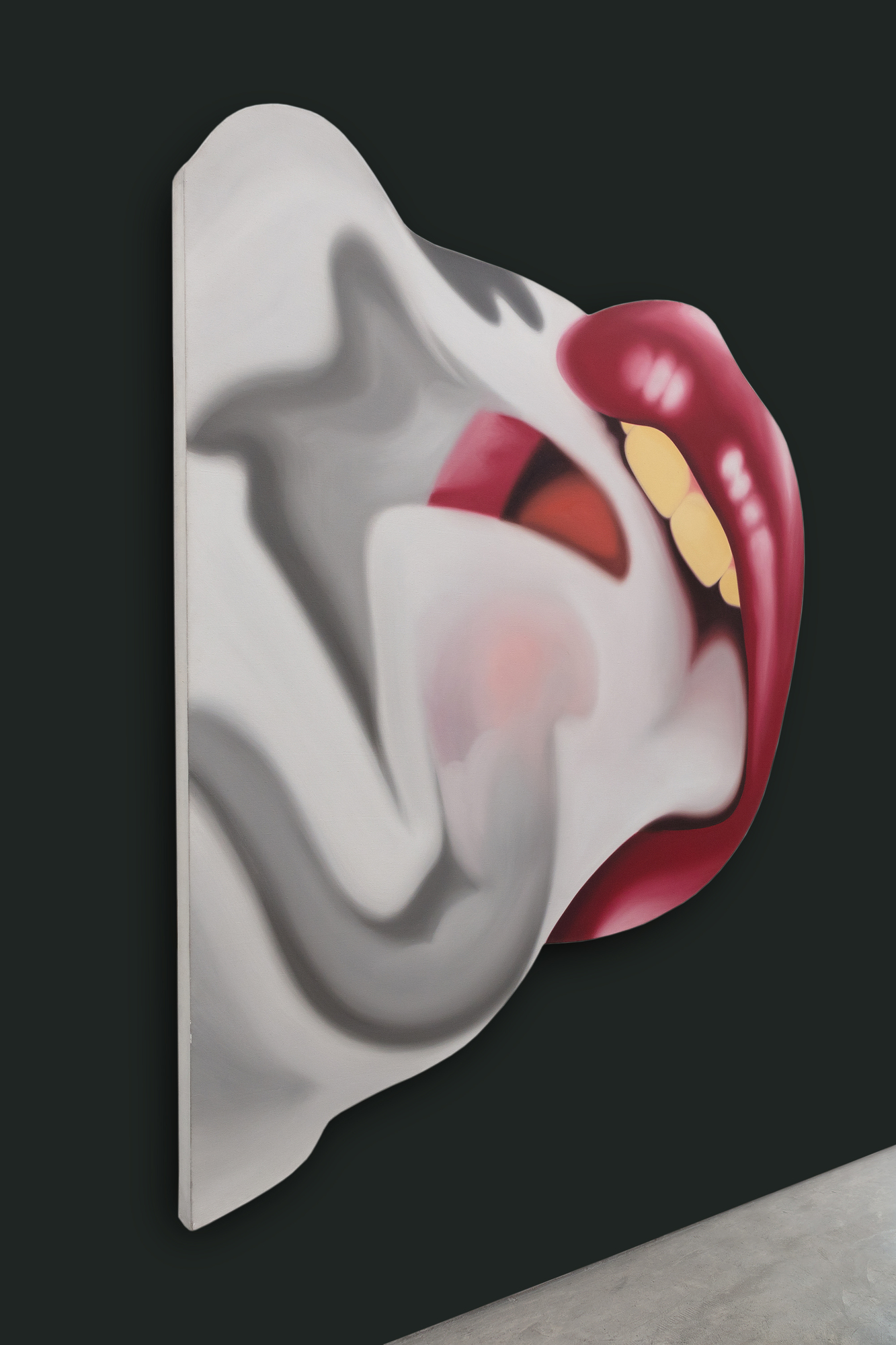

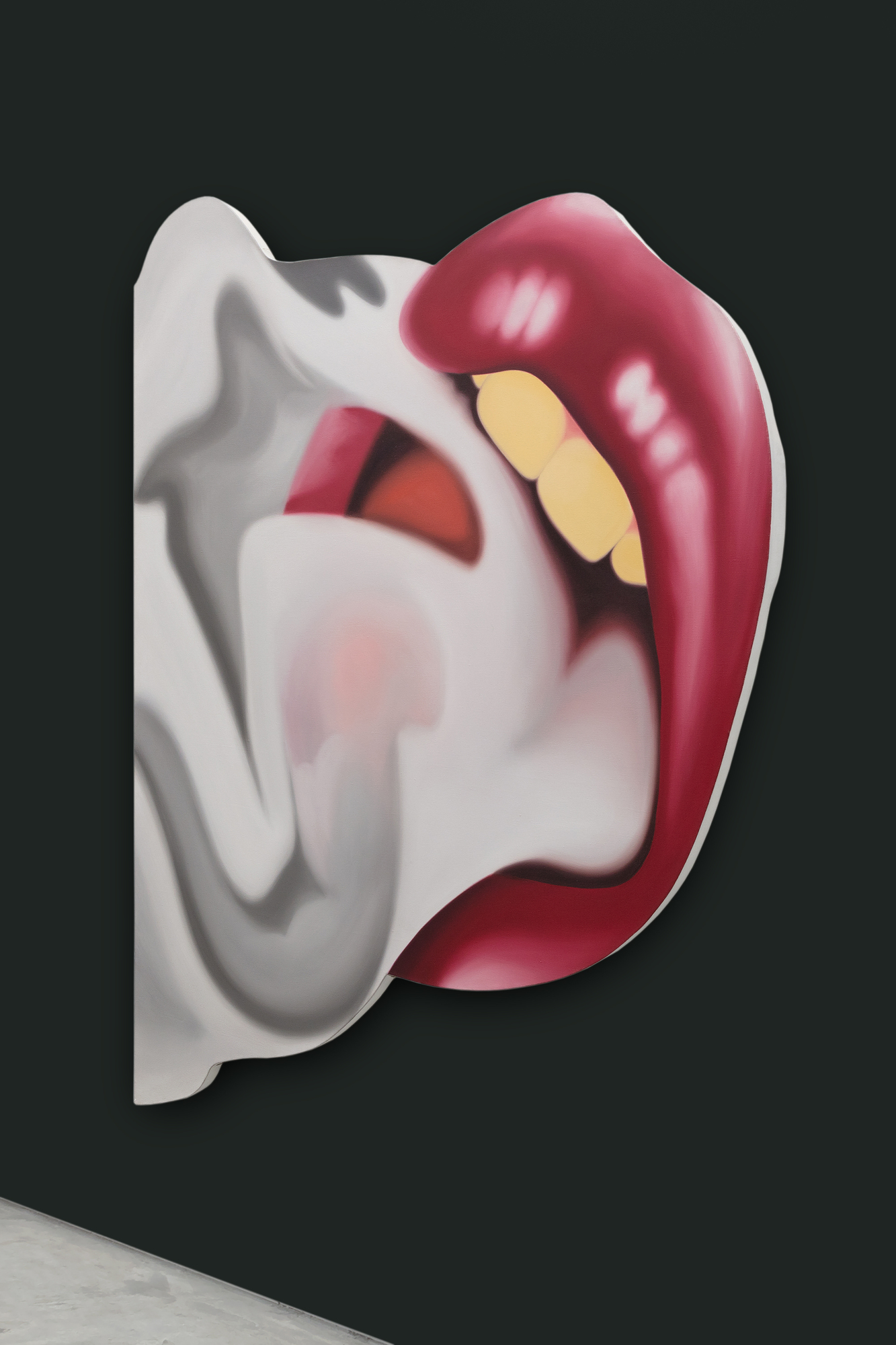

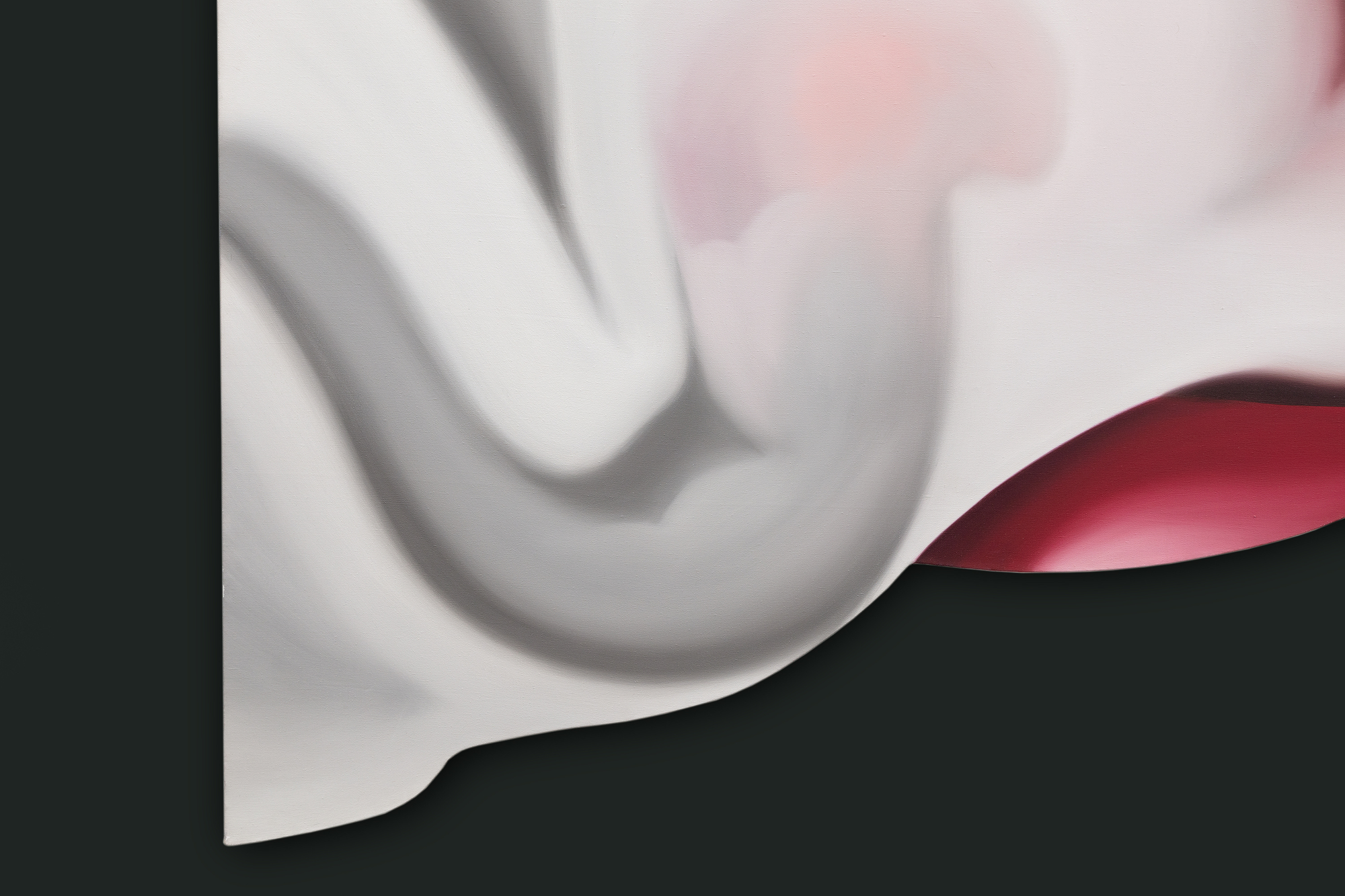

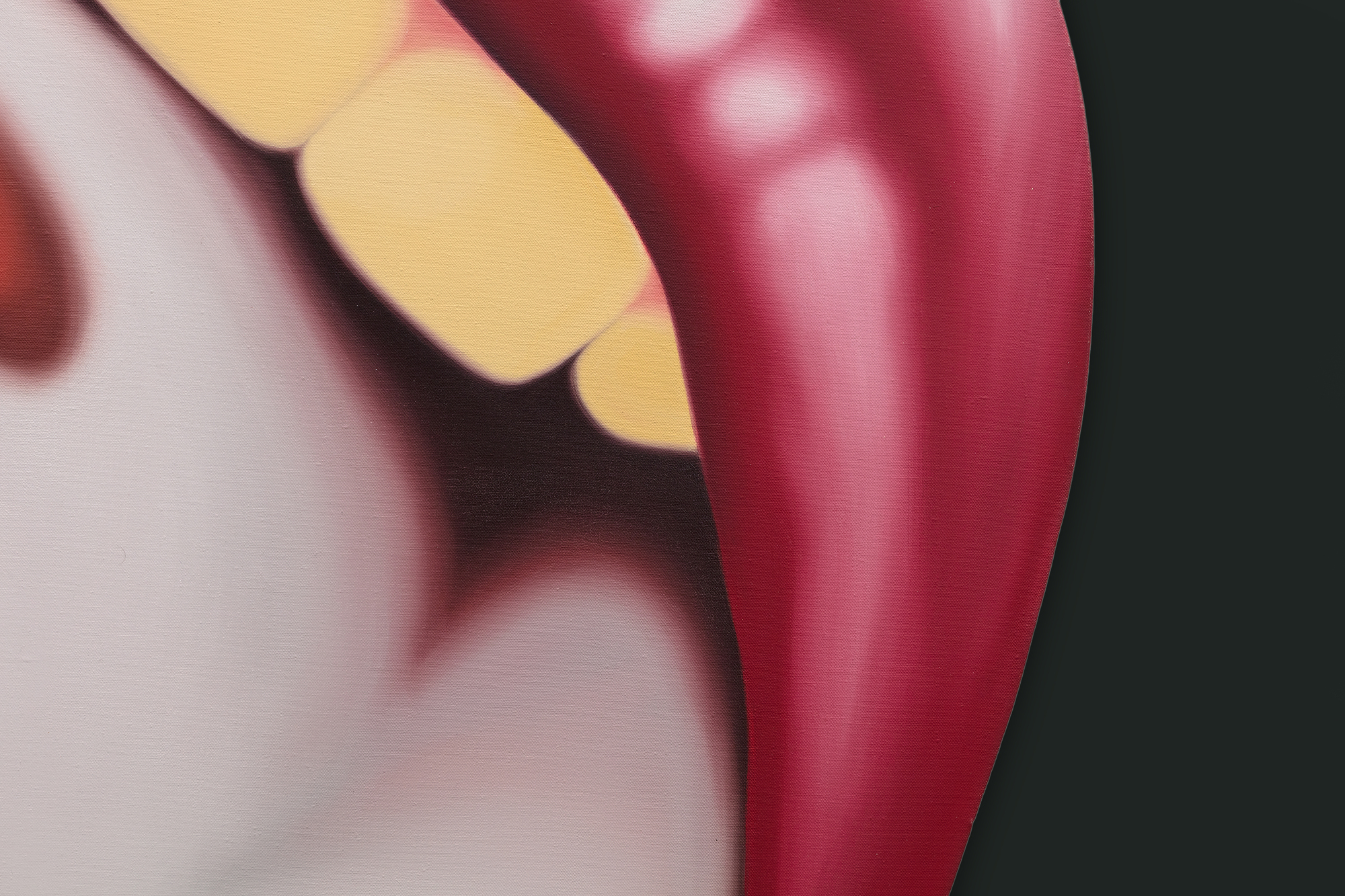

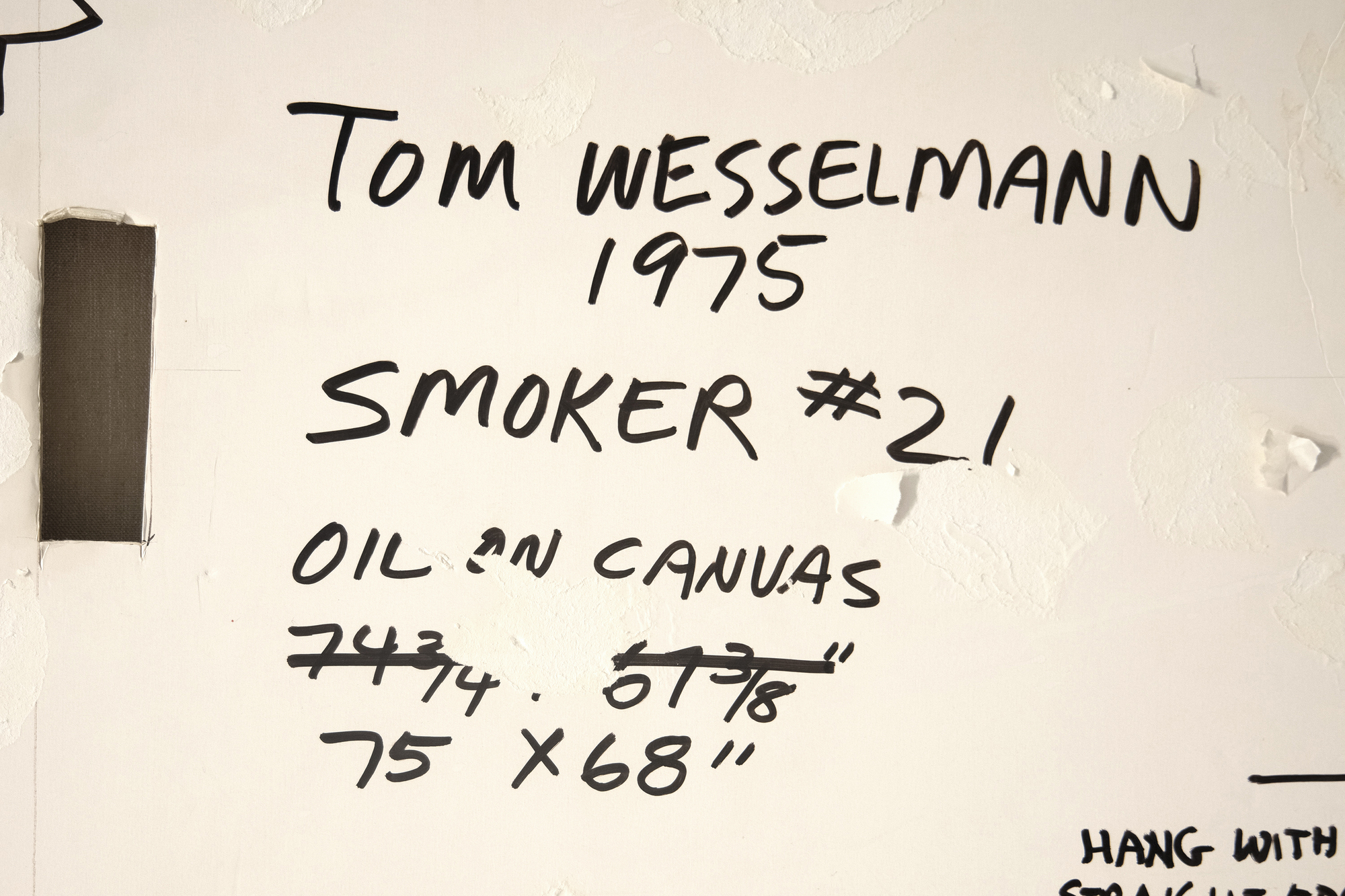

לאחר שהכניס את עצמו מבלי משים לשיחת הפופ ארט עם סדרת העירום האמריקאית הגדולה שלו, טום ווסלמן בילה את שארית הקריירה שלו בהסבר שהמוטיבציה שלו לא הייתה להתמקד יתר על המידה בנושא או ליצור פרשנות חברתית, אלא במקום זאת, לתת צורה למה שהגדיר אותו הכי יפה ומרגש. סדרת הפה המפורקת שלו מ-1965 קבעה שדימוי לא צריך להסתמך על אלמנטים זרים כדי לתקשר משמעות. אבל היו אלה הופעות ההמשך שלו עם הסדרה "מעשן" והפיתוי המפתה והפטיש שלה שהעלו את מעמדו בקרב סיבריטים אמיתיים בכל מקום. מלבד תפיסת העישון כמגניב ושיקי, ציור כמו Smoker #21 הוא חגיגה מושלמת של יכולותיו של וסלמן כצייר. ווסלמן, שהתפתה לעשן הגלי, הקפיד לתאר במדויק את תנועותיו המרושעות ולהתבונן בהפסקות הרגעיות שהגבירו את הערכתו לטבעו החושני. כמו כל יצירות האמנות המופלאות של וסלמן, ל-Smoker #21 יש נוכחות שולטת של מזבח. הוא הופק במשך שעות ארוכות בסטודיו המרשים שלו במנהטן בקופר סקוור, והתוצאה היא דינמיות לוהטת — מעוררת השראה, חושנית, מפתה, מלוטשת, עסיסית ואולי אפילו מרושעת — ציור שמתהדר בעליונותו הגרפית ובריאליזם העוצמתי שלו, המעוטר בכשרון הסקס אפיל הפטנטי שלו.

תמונות מקור

טום וסלמן הרחיב על ההצלחה של העירומים האמריקאים הגדולים שלו על ידי התמקדות במאפיינים ייחודיים של נושאיו והחל לצייר את סדרת הפה שלו בשנת 1965. ב-1967, חברתו של וסלמן, פגי סרנו, השתהתה לסיגריה בזמן שדגמנה לסדרת "הפה של ווסלמן", בהשראת ציורי המעשן שלו. פיסות העשן היו מאתגרות לצביעה ודרשו מווסלמן להשתמש בתצלומים כחומר מקור כדי ללכוד כראוי את אופיו הארעי של העשן. התמונות כאן מראות את וסלמן מצלם את חברתו, התסריטאית דניל תומפסון, כשהיא מתחזה לכמה מתמונות המקור של וסלמן.

תוצאות מובילות במכירה פומבית

"עירום אמריקאי גדול מס' 48" (1963) נמכר ב-10,681,000 דולר.

"מעשן #9" (1973) נמכר ב-6,761,000 דולר.

"מעשן #17" (1973) נמכר ב-5,864,000 דולר.

ציורים דומים שנמכרו במכירה פומבית

"מעשן #9" (1973) נמכר ב-6,761,000 דולר.

"מעשן #17" (1973) נמכר ב-5,864,000 דולר.

מעשן #5 (פה #19) (1969) נמכר ב -4,703,900 דולר.

ציורים באוספי מוזיאונים

המוזיאון לאמנות מודרנית, ניו יורק

מכון מיניאפוליס לאמנות

מוזיאון דאלאס לאמנות

המוזיאון הגבוה לאמנות, גאורגיה

מוזיאון קריסטל ברידג'ס לאמנות אמריקאית, ארקנסו

מוזיאון קרנברוק לאמנות, מישיגן

נסיונלמוסיט, נורווגיה

מוזיאון טויאמה לאמנות ועיצוב, יפן

אימות

גלריית תמונות

משאבים נוספים

לברר

עבודות נוספות של טום וסלמן

אתה יכול גם לאהוב

_tn28438.jpg )