אמיל נולדה (1867-1956)

מקור ומקור

יואכים פון לפל, נויקירכן, 1958אוסף פרטי, גרמניה

סות'ביס ניו יורק, אימפרסיוניסט ואמנות מודרנית מכירת ערב: יום שלישי, 2 בנובמבר 2010, Lot 00021

אוסף פרטי, ניו יורק

ספרות

מרטין אורבן, אמיל נולדה, קטלוג ראיזונה של ציורי השמן, כרך א'. שתיים, 1951-1915, לונדון, 1990, מס' 1250, מאויר עמ' 511היסטוריה

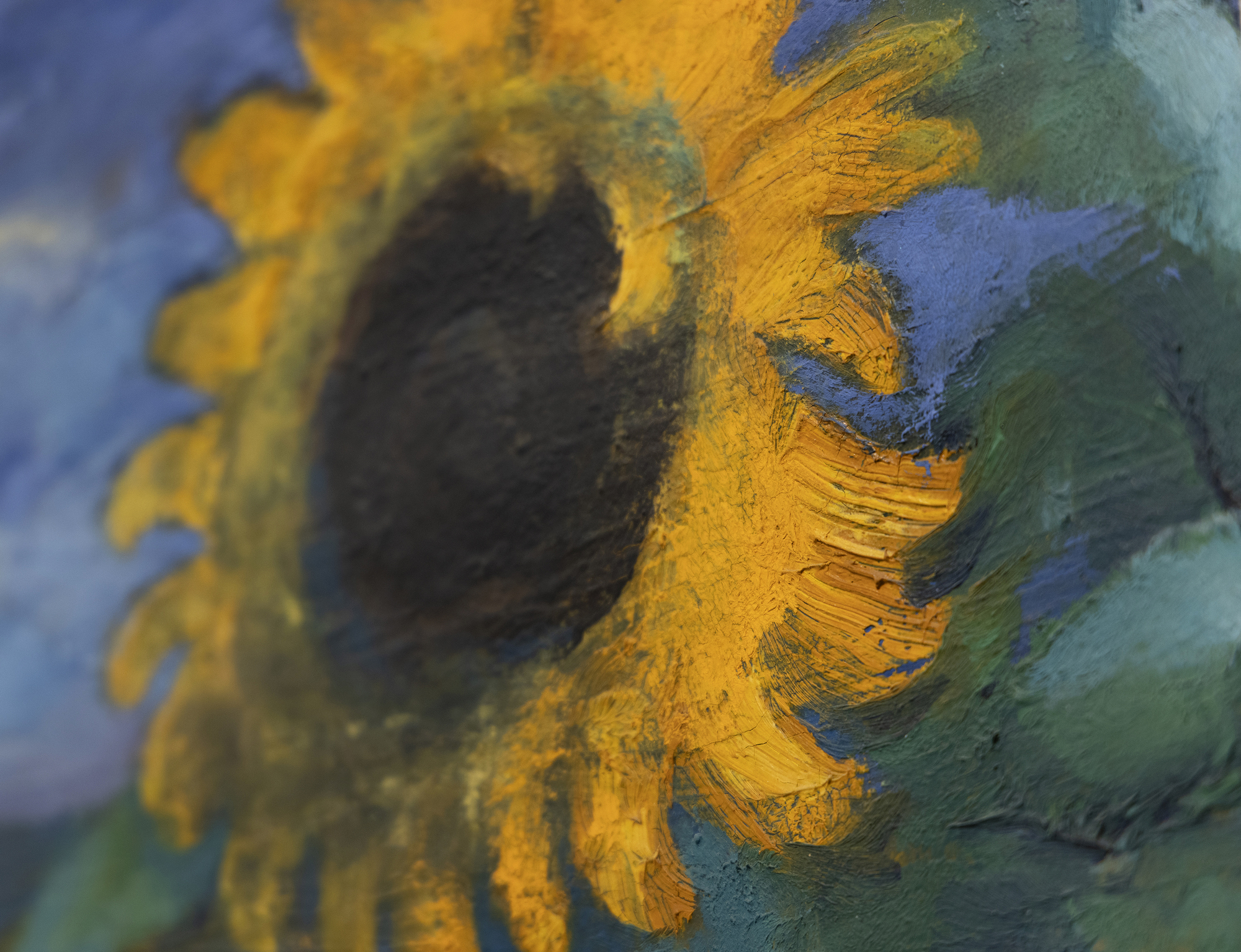

אמיל נולדה, שהוכשר כמגלף עץ, היה כמעט בן 30 לפני שיצר את ציוריו הראשונים. הציורים המוקדמים דמו לרישומים ולחיתוכי העץ שלו: דמויות גרוטסקיות עם קווים נועזים וניגודים חזקים. הסגנון היה חדש, והוא היווה השראה לתנועה המתהווה Die Brücke (הגשר), שחבריה הזמינו את נולדה להצטרף אליהם בשנת 1906. אבל, רק כשהגן הפך למוקד שלו ב-1915, הוא בנה על שליטתו בבהירות מנוגדת כדי להתמקד בצבע כאמצעי הביטוי העליון. מאוחר יותר, נולד טען ש"צבע הוא כוח, כוח הוא חיים", והוא לא יכול היה לאפיין טוב יותר מדוע ציורי הפרחים שלו מחדשים את תפיסת הצבע שלנו.

הרבה מהעוצמה של רגישויות הצבעים הדרמטיות, דמויות הווגנריות, של נוילדה היא ההשפעה של בימוי צבעי יסוד, כמו האדומים העמוקים והצהובים הזהובים של זוננבלומן, אבנד השני, על רקע פלטת צבעים קודרת. הניגודיות מדגישה ומעמיקה את זוהר הפרחים, לא רק מבחינה ויזואלית, אלא גם מבחינה רגשית. ב-1937, כשאמנותו של נולדה, נדחתה, הוחרמה וטומאה, ציוריו הוצגו כ"אמנות מנוונת" ברחבי גרמניה הנאצית בגלריות מוארות באפלולית. למרות הטיפול הזה, מעמדו של נולדה כאמן מנוון נתן לאמנותו מרחב נשימה רב יותר משום שניצל את ההזדמנות לייצר יותר מ-1,300 צבעי מים, שאותם כינה "תמונות לא מצוירות". סגנון הציור שלו, שאינו טירון בטיפול בצבעי מים, היה סימן ההיכר של השטיפות השקופות והטעונות ביותר שלו מאז 1918. Sonnenblumen, Abend II, שצויר בשנת 1944, הוא שמן נדיר בזמן מלחמה. הוא נתן לדמיונו להשתולל עם עבודה זו, והשימוש שלו בטכניקות רטובות על רטובות הגביר את הדרמה של כל עלי כותרת.

העיסוק האינטנסיבי של נולדה בצבע ובפרחים, במיוחד חמניות, משקף את מסירותו המתמשכת לוואן גוך. הוא היה מודע לוואן גוך כבר ב-1899, ובמהלך שנות ה-20 ותחילת שנות ה-30 של המאה ה-20 ביקר בכמה תערוכות של יצירתו של האמן ההולנדי. הם חלקו אהבה עמוקה לטבע. מסירותו של נולדה להבעה והשימוש הסמלי בצבע מצאו מלאות בנושא החמניות, וזה הפך לסמל אישי עבורו, כפי שקרה לוואן גוך.

תובנות שוק

- ציורי חמניות ממומשים במלואם כמעט ואינם זמינים, ורוב העבודות בנושא זה נמצאות במוסדות המוזיאון.

- כאשר ציורי פרחים הגיעו למכירה פומבית, הם היו בין היצירות הנמכרות ביותר של נולדה.

- כפי שממחיש הגרף של Art Market Research, השוק של אמיל נולדה העריך 648.1% מאז 1976.

תוצאות מובילות במכירה פומבית

"הרבסטמיר ה-16" (1911) נמכר ב-7,344,500 דולר.

"Indische Tänzerin" (1917) נמכר ב-5,262,500 דולר.

"Rotblondes Mädchen" (1919) נמכר ב-3,826,851 דולר.

"Sonnenuntergang" (1909) נמכר ב-3,517,759 דולר.

ציורים דומים שנמכרו במכירה פומבית

"Meer I" (1947) נמכר ב-3,132,800 דולר.

- צויר שלוש שנים אחרי זוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- מעט קטן יותר מזוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- במקום פרחים, מיר הראשון הוא נוף ים, נושא נוסף שנולדה תיקן לעתים קרובות בתקופה זו

"Kleine Sonnenblumen" (1946) נמכר ב-3,042,500 דולר.

- צויר שנתיים אחרי זוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- מעט קטן יותר מזוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- כולל גם נושא חמניות

- ציור זה נכלל ברטרוספקטיבה של Nolde משנת 2014 במוזיאון לואיזיאנה לאמנות מודרנית, דנמרק

"Üppiger Garten" (1945) נמכר ב-2,658,500 דולר.

- צויר שנה לאחר זוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- מעט גדול יותר מזוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- אמנם לא תיאור של חמניות, אבל Üppiger Garten הוא נוף פרחוני דומה חתוך היטב

"Grosse Sonnenblume und Clematis" (1943) נמכר ב-2,179,094 דולר.

- צויר שנה לפני זוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- מעט קטן יותר מזוננבלומן, אבנד השני

- אותו נושא חמניות