ג'ורג'יה אוקיף(1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

מקור ומקור

מקום אמריקאי, ניו יורקמר וגברת מקס אסקולי, ניו יורק, 1944

ירד במשפחה

הרולד דיאמונד, ניו יורק, 1975 בקירוב

גלריית ג'רלד פיטרס, סנטה פה, ניו מקסיקו

גלריית איליין הורביץ', סקוטסדייל, אריזונה, 1978

אוסף של מר וגברת פרי תומאס, לאס וגאס, נבאדה, 1978

אוסף פרטי, ארצות הברית

תערוכה

ניו יורק, ניו יורק, מקום אמריקאי, ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, ציורים – 1943, 11 בינואר – 11 במרץ 1944, מס' 8ווסט פאלם ביץ', פלורידה, גני הפסלים אן נורטון, דיסקברי... עוד...ng Creativity: American Art Masters, 10 בינואר - 17 במרץ 2024

ספרות

ליינס, ברברה בולר, ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, קטלוג Raisonné כרך שני (ניו הייבן ולונדון: הוצאת אוניברסיטת ייל, 1999), חתול. מס' 1066, עמ' 670.... פחות...

היסטוריה

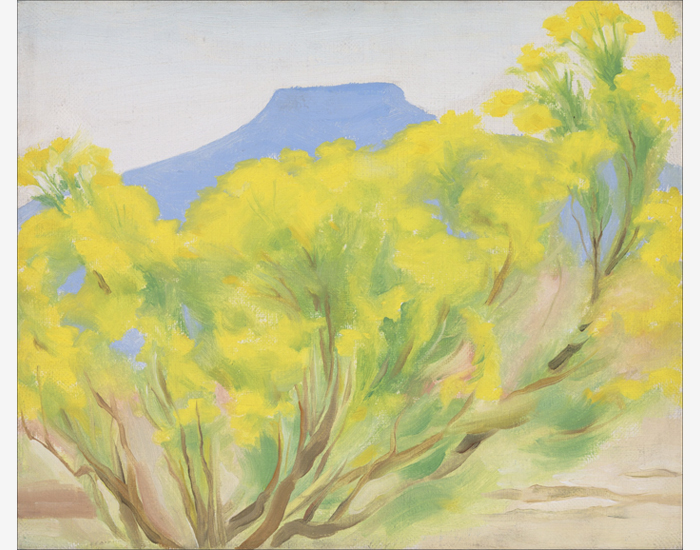

Cottonwood Tree (ליד אביקיו), ניו מקסיקו (1943) מאת האמנית האמריקאית הנודעת ג'ורג'יה אוקיף הוא מופת לסגנון האוורירי והנטורליסטי יותר שהמדבר נתן בה השראה. לאוקיף הייתה זיקה רבה ליופיו הייחודי של דרום-מערב ארצות הברית, והיא עשתה שם את ביתה בין העצים המסתובבים, הנופים הדרמטיים וגולגולות החיות הלבנות שהיא ציירה לעתים קרובות כל כך. או'קיף התגורר בחוות הרפאים, חווה של בחורים במרחק של 12 ק"מ מחוץ לכפר אביקיו שבצפון ניו מקסיקו, וצייר שם את עץ הכותנה הזה. הסגנון הרך יותר כיאה לנושא זה הוא סטייה מהנופים האדריכליים הנועזים שלה ומהפרחים בגווני התכשיטים שלה.

עץ הכותנה מופשט לחלקות רכות של ירוקים ירוקים שדרכם נראים ענפים מסומנים יותר, מתפתלים בחלל כנגד כיסים של שמיים כחולים. הדוגמנות של הגזע והאנרגיה העדינה בעלים מובילות קדימה ניסויים קודמים עם העצים האזוריים של צפון מזרח המדינה שכבשו את אוקיף שנים קודם לכן: מייפל, ערמונים, ארזים וצפצפות, בין היתר. שני בדים דרמטיים משנת 1924, עצי סתיו, המייפל ואפור הערמונים, הם מקרים מוקדמים של מרכזיות לירית ונחושה, בהתאמה. כפי שניתן לראות בציורי העצים המוקדמים הללו, אוקיף הגזימה ברגישות הנושא שלה בצבע ובצורה.

עודתובנות שוק

על פי הגרף שהוכן על ידי Art Market Research, מחירי השוק של ג'ורג'יה אוקיף עלו בשיעור תשואה שנתי מורכב של 12.7% מאז 1976.

שיא המכירות הפומביות של ג'ורג'יה אוקיף נקבע בשנת 2014 עם מכירת Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 תמורת יותר מ-44.4 מיליון דולר. זהו עדיין הסכום הגבוה ביותר ששולם עבור אמנית במכירה פומבית.

גם כאשר השוק של אוקיף רשם ירידה קלה במהלך המגפה בשנת 2020 (כפי שניתן לראות בגרף AMR), המדד העולמי של ArtPrice למחזור המכירות הפומביות מראה כי אוקיף עלה מהמקום ה-263 לאמן הנמכר ביותר באותה שנה, מה שממחיש כי ציוריו של אוקיף נותרו בביקוש גובר, במיוחד בהשוואה לביצועים של אמנים אחרים באותה תקופה.

- בממוצע במהלך 40 השנים האחרונות, רק 4 ציורים של אוקיף עומדים למכירה פומבית מדי שנה.

תוצאות מובילות במכירה פומבית

"עשב ג'ימסון / פרח לבן מס' 1" (1932) נמכר תמורת $44,405,000.

"ורד לבן עם לרקספור לא. אני" (1927) נמכר ב-26,725,000 דולר.

"איריס שחור שישי" (1936) נמכר ב-21,110,000 דולר.

"עלה סתיו II" (1927) נמכר ב-15,275,000 דולר.

ציורים דומים שנמכרו במכירה פומבית

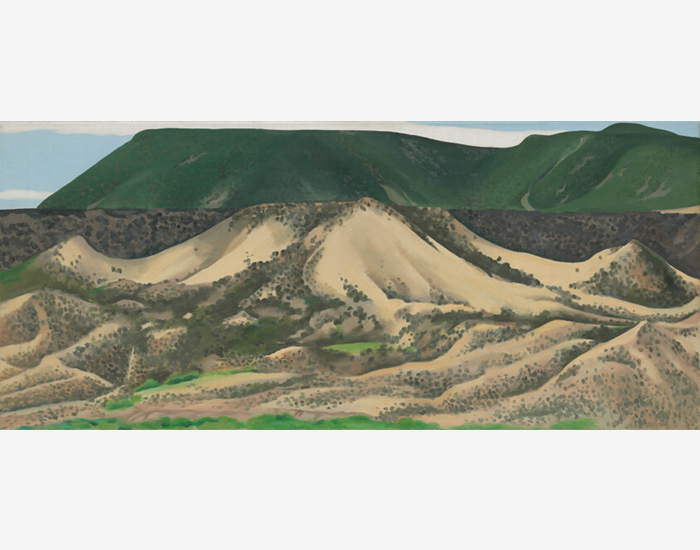

"גבעות אדומות עם פדרנל, עננים לבנים" (1936) נמכר ב-12,298,000 דולר.

- ציור זה, מבט רחב יותר על הנוף המדברי, נמכר במכירה הפומבית של האוסף של מייסד מיקרוסופט פול אלן

- הטבע היה לעתים קרובות הנושא של האמנות של אוקיף, וכמה עצי כותנה ניתן לראות מרחוק של הנוף הזה

"לייק ג'ורג' עם ליבנה לבנה לבנה" (1921) נמכר ב-11,292,000 דולר.

- בד מוקדם זה עם נושא דומה, אם כי בקנה מידה קטן יותר, נמכר עבור מעל 11.2 מיליון דולר בשנת 2018, מחיר המכירה הפומבית השלישי בגובהו עבור אוקיף

- נושאי טבע, במיוחד עצים, היו מוקד תכוף של אוקיף

"ליד אביקיו, ניו מקסיקו" (1931) נמכר ב-8,412,500 דולר.

- יצירה קטנה יותר מעץ קוטוןווד (ליד אביקיו), ניו מקסיקו

- נוף מוקדם יותר מאותו אזור בניו מקסיקו, יצירה זו נמכרה ביותר מ-8.4 מיליון דולר ב-2018

"המייפל האדום באגם ג'ורג'" (1926) נמכר ב-8,187,500 דולר.

- נושא טבע זה של אוקיף באותו גודל נמכר בשנת 2018 עבור מעל 8.18 מיליון דולר

- דוגמה מוקדמת יותר משנת 1926

"צורות טבע – גספה" (1931) נמכר ב-6,870,200 דולר.

- נושא טבע מופשט בקנה מידה קטן

- נמכר לאחרונה ביותר מ-6.87 מיליון דולר

מחסור

- 43% מציוריו של אוקיף כבר מוחזקים באוספי מוזיאונים.

- מתוך 616 עבודות שמן על בד שאוקיף צייר, פחות מ-300 נותרו זמינות לאוספים פרטיים.

- ככל שיעבור הזמן, רבים מציורי אוקיף הנמצאים כיום באוספים פרטיים יורישו למוזיאונים, וישאירו מעט מאוד מהם זמינים אי פעם.

- אוקיף צייר לראשונה את עצי הכותנה באביקיו במשך שנתיים בלבד, מ-1943 עד 1945, ויצר רק תשעה ציורים לסדרה מרכזית זו. מתוכם, 6 מוחזקים באוספי מוזיאונים קבועים, ורק 3 נותרו בידיים פרטיות.

- עצי הכותנה של אוקיף – מסדרת הליבה המקורית של 1943-1945 ומשנים מאוחרות יותר – נמצאים באוספי מוזיאונים מובילים, כולל מוזיאון ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, מכון באטלר לאמנות אמריקאית והמוזיאון לאמנויות יפות בוסטון.

ציורים של עצי כותנה, עצים ואביקיו באוספי המוזיאון

מוזיאון ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, סנטה פה

מוזיאון סנטה ברברה לאמנות

מוזיאון ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, סנטה פה

מכון באטלר לאמנות אמריקאית, אוהיו

מוזיאון ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, סנטה פה

מוזיאון קליבלנד לאמנות

מוזיאון דאלאס לאמנות

מוזיאון ניו מקסיקו לאמנות, סנטה פה

המוזיאון לאמנויות יפות, בוסטון

מוזיאון ברוקלין, ניו יורק

מוזיאון המטרופוליטן לאמנות, ניו יורק

מוזיאון ויטני לאמנות אמריקאית, ניו יורק

מוזיאון ג'ורג'יה אוקיף, סנטה פה

מוזיאון קליבלנד לאמנות

המכון לאמנות של שיקגו

גלריית תמונות

משאבים נוספים

אימות

עץ הכותנה (ליד אביקיו), ניו מקסיקו, 1943 מופיע כמספר 1066 בקטלוג של ברברה בוהלר ליינס על יצירת האמנות של ג'ורג'יה אוקיף. הציור מאויר בעמוד 670 בכרך השני.

ראה קטלוג Raisonné

לברר

אתה יכול גם לאהוב