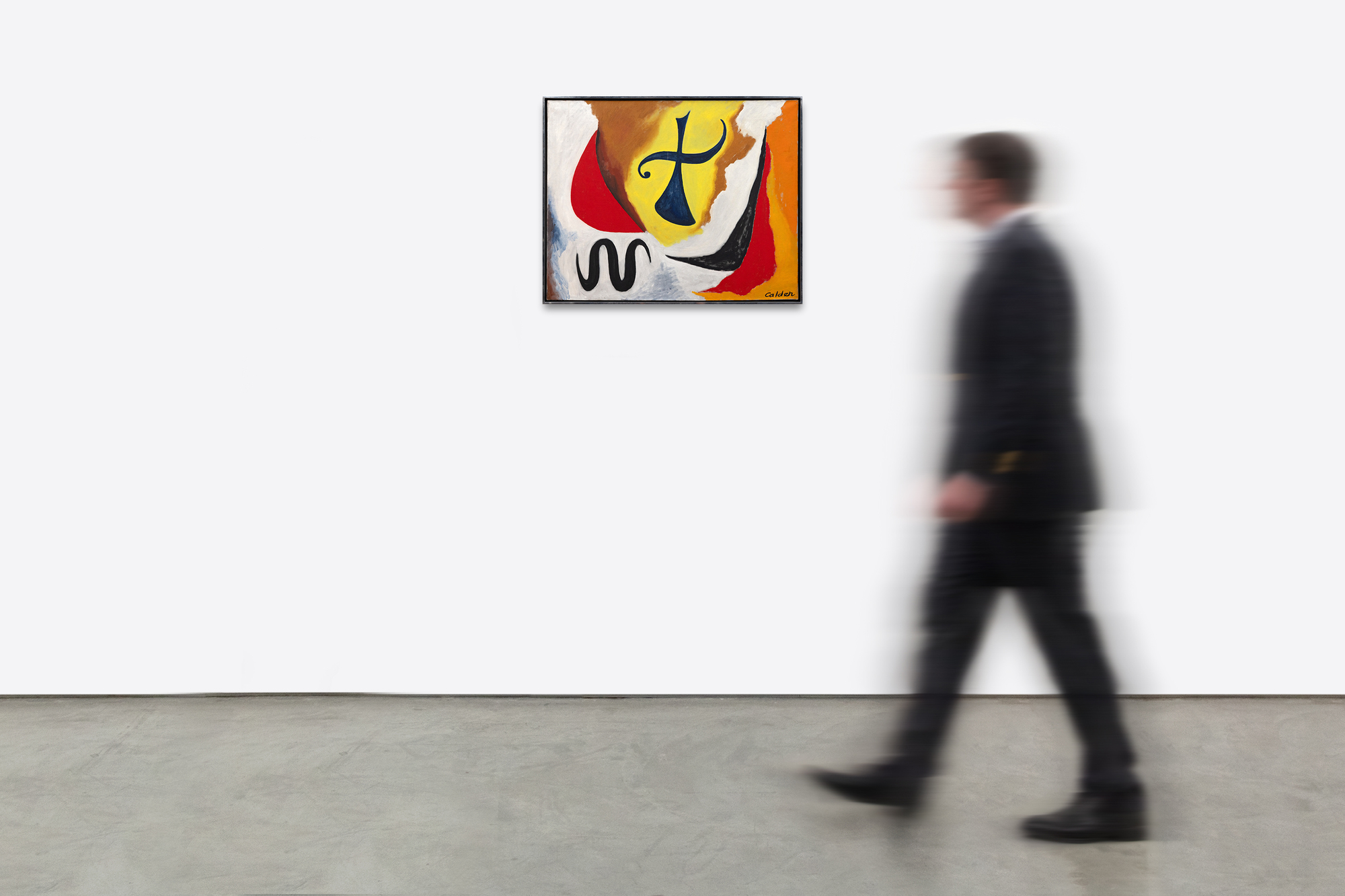

アレクサンダー・カルダー (1898-1976)

出所

Perls Gallery(ニューヨーク個人蔵、上記より入手

展示会

クレイン・ギャラリー、ロンドン、カルダー。油絵、グワッシュ、モビール、タペストリー、1992年3月5日-5月1日歴史

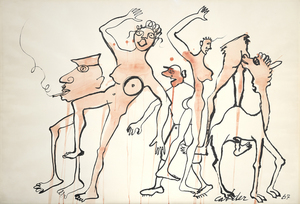

アレクサンダー・カルダーは、1940年代後半から1950年代前半にかけて、驚くほど多くの油彩画を制作している。この頃には、1930年にモンドリアンのアトリエを訪れ、絵画ではなくその環境に感銘を受けた衝撃が、カルダー独自の芸術言語として発展していたのである。1948年に《十字架》を描いているとき、カルダーはすでに国際的に認められつつあり、1952年の第26回ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレの彫刻部門の大賞を受賞するところまで来ていたのである。カルダーは、彫刻の制作と並行して絵画の制作も行い、同じ形式言語と形と色彩の卓越性で両方の媒体に取り組みました。

カルダーは、物体を動かし続ける目に見えない力に深い興味を抱いていた。この関心を彫刻からカンバスに移すと、カルダーは 「十字架」の平面とバランスを変化させることによって、その中にトルク感を作り出したことがわかる。その結果、十字架が前方に押し出されるような、あるいは上空から降りてくるような、暗黙の運動が生み出されたのである。十字架》の決定的な勢いは、被写体が強調するように伸ばした腕、左側の拳のような曲線ベクトル、シルエットになった蛇のような人物などのディテールによってさらに増幅される。

カルダーはまた、「十字架」の表面全体に、詩的な放棄の強い糸を採用している。それは親友ミロのヒエラルキーに満ちた、明らかに個人的な視覚言語と共鳴しているが、この絵のさまざまな要素の効果的なアニメーションは、すべてカルダーによるものである。カルダーは、そのキャリアを通じて、形と構図を理解する上で和気あいあいとした柔軟性を保ち続け、これほど詩的なライセンスを獲得したアーティストはいなかった。彼は他人の無数の解釈をも歓迎し、1951年にこう書いている。"私が考えていることを他人が理解することは、少なくとも彼らが他の何かを持っている限り、重要ではないようだ "とね。

いずれにせよ、《十字架》が第二次世界大戦の激動の直後に描かれたことは忘れてはならないし、人によっては当時のことを痛切に反映しているように見えるかもしれない。そして何より、アレクサンダー・カルダーがまず筆を走らせ、形や構造、空間の関係、そして最も重要な動きについて考えを巡らせたことが、この《十字架》で証明されている。

マーケットインサイト

- アート・マーケット・リサーチ社のグラフによると、1976年1月以降、カルダーの作品の価値は5068.8%上昇していることがわかります。この同じ8年間で、カルダーの作品の年間収益率は8.7%であった。

- 2つ目のグラフでは、カルダーの作品の価値が2014年11月以降66%上昇し、年率6.3%の収益率をもたらしていることが分かります。

- カルダーは多作な画家でしたが、「十字架」のようなキャンバスに油彩で描かれた作品は、彼の作品の中でも特に希少なものです。

オークションで落札された絵画

"Personnage" (1946)は1,865,000米ドルで落札されました。

- 十字架』の2年前に描かれた作品

- 似たような色合いだが、「The Cross」の方がより親近感がわく抽象的な表現になっている

- 2014年にオークションで落札されたこの絵は、現在なら300万円以上の価値があると思われる

"Fond rouge"(1949年)は1,815,000米ドルで落札されました。

- 十字架』のちょうど1年後に描かれた作品

- 素晴らしい抽象画だが、構図的には「十字架」ほど刺激的ではない

- こちらの背景は一色ですが、The Crossは複数の色相をバランスよく配置しています