エミール・ノルデ(1867-1956)

出所

ヨアヒム・フォン・レーペル、ノイキルヒェン、1958年ドイツ、個人蔵

サザビーズ・ニューヨーク、印象派&モダンアート・イヴニングセール。2010年11月2日(火)、Lot 00021

ニューヨーク、個人蔵

文学

マーティン・アーバン『エミール・ノルデ 油彩画カタログレゾネ 第2巻 1915-1951』ロンドン、1990年、第1250号、図版p.511歴史

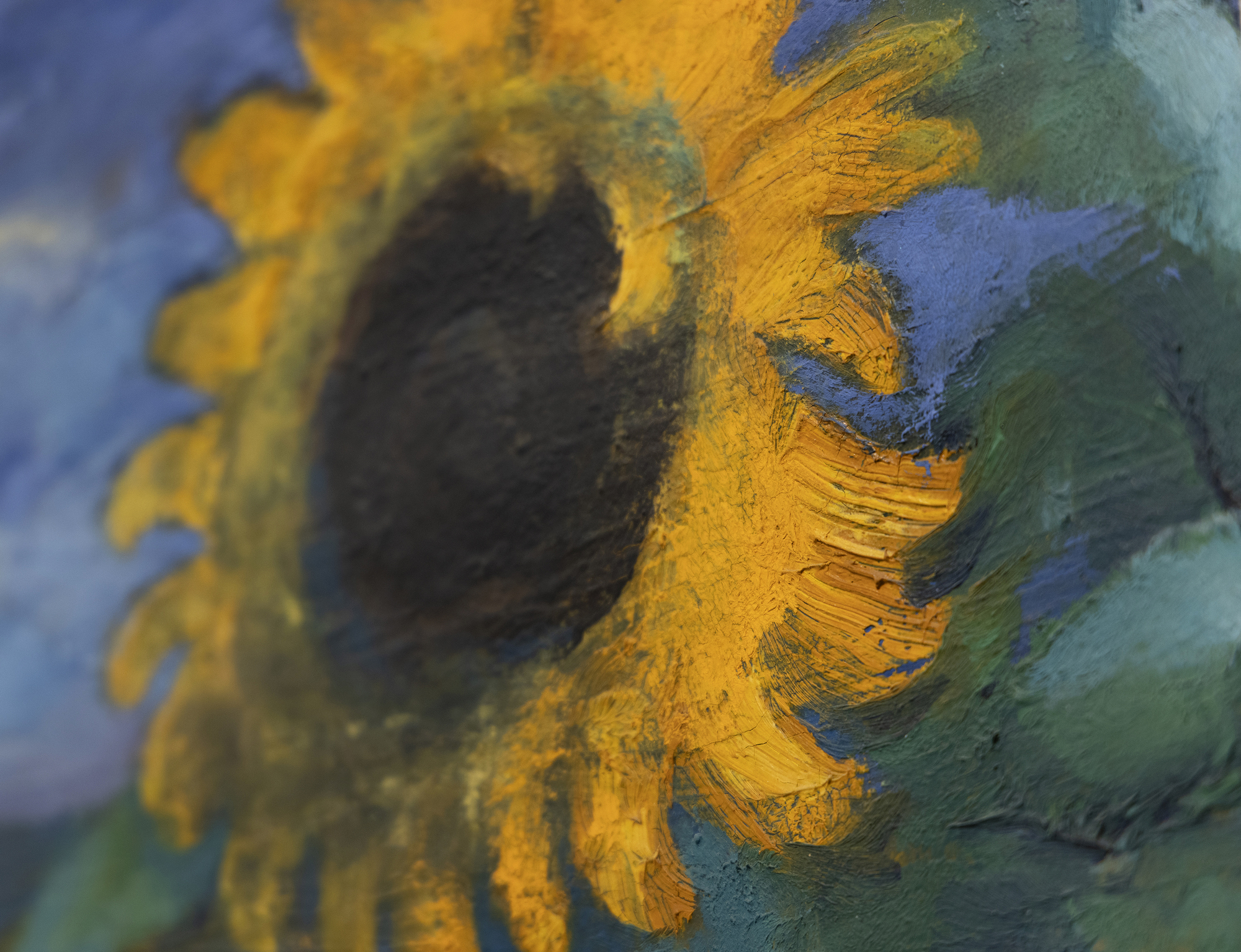

木彫り職人としての訓練を受けたエミール・ノルデは、30歳を過ぎてから初めて絵画を制作した。初期の絵画は、大胆な線と強いコントラストで描かれたグロテスクな人物像で、彼のデッサンや木版画に似ていた。そのスタイルは新しく、1906年にノルデが招待された新興の運動「Die Brücke(橋)」にインスピレーションを与えた。 しかし、1915年に庭を拠点とするようになってから、彼は対照的な輝度の習得に加え、最高の表現手段である色彩に焦点を当てるようになる。 後にノルデは「色彩は力であり、力強さは生命である」と主張したが、彼の花の絵が私たちの色彩感覚を蘇らせる理由を、これ以上ないほど言い当てているのではないだろうか。

ノルデのドラマチックでワーグナー的な色彩感覚の強さの多くは、《Sonnenblumen, Abend II》の深い赤や黄金色のような原色を、地味な色調で演出する効果である。そのコントラストは、視覚的なものだけでなく、情緒的にも花の輝きを強調し、深化させる。1937年、ノルデの芸術が拒絶され、没収され、汚されたとき、彼の絵は「退廃芸術」としてナチス・ドイツ中の薄暗いギャラリーを練り歩いた。しかし、堕落した芸術家であるがゆえに、ノルデの芸術にはゆとりが生まれた。水彩画の扱いに慣れていない彼は、1918年以来、自由な発想で、電荷の高い透明なウォッシュを描くのが特徴であった。1944年に描かれた《Sonnenblumen, Abend II》は、戦時中の貴重な油彩画である。イマジネーションを膨らませ、ウェット・オン・ウェットの技法で花びら一枚一枚のドラマを高めた作品である。

ノルデが色彩や花、特にひまわりに強いこだわりを持つのは、ゴッホへの傾倒が続いていたためである。 ゴッホのことは1899年にはすでに知っており、1920年代から1930年代初頭にかけて、オランダの画家の展覧会を何度か訪れている。 二人は自然に対する深い愛情を共有していた。ノルデの表現への献身と象徴的な色彩の使用は、ひまわりという主題に充実感を見出し、それはゴッホにとってそうであったように、彼自身の象徴となったのである。

マーケットインサイト

- ひまわりを描いた完全な作品はほとんどなく、この主題の作品のほとんどは美術館に所蔵されています。

- 花の絵がオークションに出品されると、ノルデの作品の中で最も高く売れた作品に数えられる。

- アート・マーケット・リサーチのグラフが示すように、エミール・ノルデの相場は1976年以来648.1%も上昇している。

オークションでの上位入賞実績

"Herbstmeer XVI"(1911年)は7,344,500ドルで落札された。

"Indische Tänzerin" (1917)は5,262,500ドルで落札された。

"Rotblondes Mädchen"(1919年)が3,826,851ドルで落札された。

"Sonnenuntergang"(1909年)は3,517,759ドルで落札された。

オークションで落札された絵画

"Meer I"(1947年)が3,132,800ドルで落札された。

- Sonnenblumen』から3年後に描かれた『Abend II

- Sonnenblumen, Abend IIより若干小さい。

- Meer Iは花柄というより海景で、これもノルデがこの時期に頻繁に改訂した主題である。

"Kleine Sonnenblumen" (1946)は3,042,500ドルで落札されました。

- Sonnenblumen』から2年後に描かれた『Abend II

- Sonnenblumen, Abend IIより若干小さい。

- ヒマワリの被写体にも注目

- この絵は、2014年にルイジアナ近代美術館で開催されたノルデ回顧展に出品されたものです(デンマーク

"ウピガー・ガルテン"(1945年)が2,658,500ドルで落札されました。

- Sonnenblumen, Abend II」から1年後に描かれた作品

- Sonnenblumen, Abend IIより若干大きい。

- ひまわりを描いたものではありませんが、ÜppigerGartenは同じような花の風景をきっちり切り取っています

"Grosse Sonnenblume und Clematis" (1943)は2,179,094ドルで落札された。

- Sonnenblumen, Abend II"の1年前に描かれたもの。

- Sonnenblumen, Abend IIより若干小さい。

- 同じヒマワリの被写体