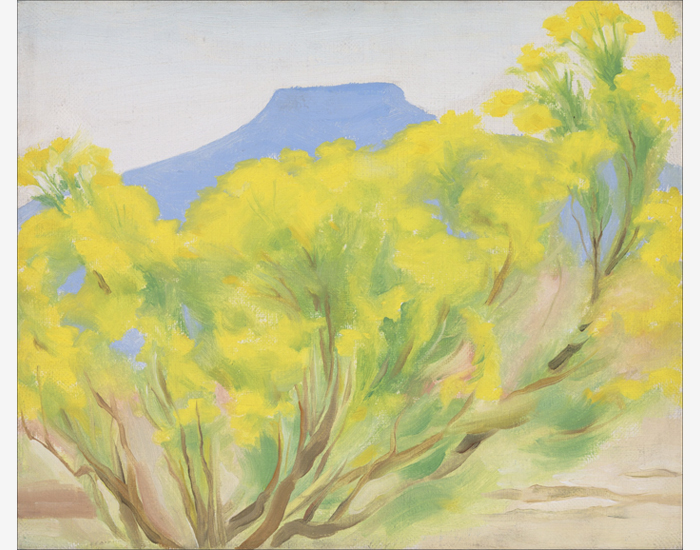

GEORGIA O'KEEFFE (1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

出所

アメリカン・プレイス、ニューヨークマックス・アスコリ夫妻(ニューヨーク、1944年

家系図

ハロルド・ダイアモンド、ニューヨーク、1975年頃

ジェラルド・ピーターズ・ギャラリー(ニューメキシコ州サンタフェ

Elaine Horwich Gallery(アリゾナ州スコッツデール、1978年

E・パリー・トーマス夫妻のコレクション、ラスベガス、ネバダ州、1978年

個人コレクション(アメリカ)

展示会

ニューヨーク、ニューヨーク、アメリカンプレイス、ジョージアオキーフ、絵画- 1943年、1月11日 - 1944年3月11日、第8号ウェストパームビーチ、フロリダ州、アンノートン彫刻庭園、ディスカバリ...もっとその。。。ng Creativity: American Art Masters、2024年1月10日〜3月17日

文学

Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Catalogue Raisonné Volume Two (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), cat.第1066号、670ページ。...少ない。。。

歴史

アメリカの著名な画家ジョージア・オキーフの「綿の木(アビキュー付近)、ニューメキシコ 」(1943年)は、砂漠が彼女に与えた、より風通しの良い、より自然なスタイルの典型例です。オキーフは、南西部の独特の美しさに非常に親近感を覚え、そこで、しなびた木々、ドラマチックな景色、漂白された動物の頭蓋骨などを頻繁に描き、住まいとした。オキーフは、ニューメキシコ州北部のアビキウの村から12マイル離れたゴースト・ランチに住み、その周辺でこのコットンウッドの木を描いています。大胆な建築物の風景や宝石をちりばめたような花々とは一線を画す、この被写体にふさわしい柔らかな作風が特徴です。

綿の木は、青々とした緑の柔らかなパッチに抽象化され、その間からより繊細な枝が見え、青空のポケットを背景に空間を螺旋状に広がっています。幹の造形と葉の繊細なエネルギーは、オキーフが何年も前に魅了された北東部の地方樹であるカエデ、栗、杉、ポプラなどに対する過去の実験を引き継いでいる。1924年に制作された2つのドラマチックなキャンバス「秋の木々、カエデ」と「栗の木」は、それぞれ叙情的で毅然とした中心性を示す初期の例である。これらの初期の樹木画に見られるように、オキーフは色彩と形態で対象の感性を誇張している。

もっとそのマーケットインサイト

-

アート・マーケット・リサーチのグラフによると、1976年以降、オキーフの絵画は年率11.6%で増加していることがわかる。

-

2014年の記録的なセール(Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1、4440万ドル超で落札)以来、ジョージア・オキーフ市場では、シグネチャースタイルの油彩画の需要がますます高まっています。

-

オキーフの市場が2020年のパンデミック時に若干下降した時(AMRのグラフに見られるように)でも、ArtPriceのオークション売上高のグローバルインデックスでは、オキーフはその年の263位から63位まで上昇し、特にこの同時期の他の作家のパフォーマンスと比較すると、オキーフの絵画が依然として需要が高まっていることを示しています。

オークションでの上位入賞実績

"ジムゾン・ウィード/白い花No.1"(1932年)は44,405,000ドルで落札された。

"White Rose with Larkspur No. I" (1927)は26,725,000ドルで落札された。

"Autumn Leaf II" (1927)は15,275,000ドルで落札された。

"A Street" (1926)は13,285,500円で落札されました。

オークションで落札された絵画

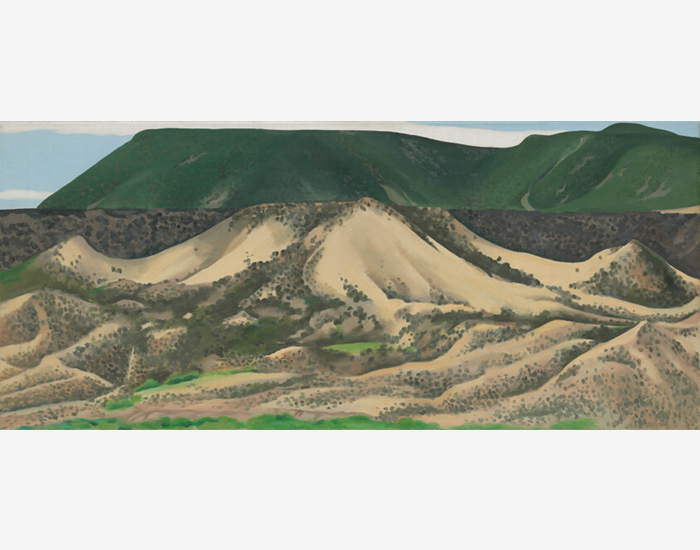

"Red Hills with Pedernal, White Clouds" (1936)は12,298,000ドルで落札された。

- 砂漠の風景をより広く描いたこの絵は、マイクロソフトの共同創業者ポール・アレン氏のコレクションのオークションで落札されたものです

- オキーフは自然を題材にした作品を多く制作しており、この風景画の遠景にはコットンウッドの木がいくつか見える。

"Lake George With White Birch"(1921年)は11,292,000ドルで落札されました。

- 規模は小さいが似たような題材のこの初期のキャンバスは、2018年に1120万ドル超で落札され、オキーフのオークション価格としては3番目に高い金額となった

- 自然、特に樹木は、オキーフの作品の中で頻繁に取り上げられた。

"Near Abiquiu, New Mexico" (1931)は8,412,500ドルで落札された。

- ニューメキシコ州「コットンウッドツリー」(アビキュー近郊)より小さい作品

- ニューメキシコ州の同じ地域で撮影された初期の風景画で、2018年に840万ドル以上の価格で落札された作品です

"The Red Maple at Lake George"(1926年)は8,187,500ドルで落札された。

- このオキーフの自然を題材にした同サイズの作品は、2018年に818万円以上で落札されました

- 1926年の初期の例

"Nature Forms - Gaspé"(1931年)は6,870,200ドルで落札された。

- 小規模で抽象的な自然の被写体

- 最近687万ドル以上で落札された

SCARCITY

-

オキーフの絵画の43%はすでに美術館に所蔵されている。

-

オキーフが描いた716点の油彩・キャンバス作品のうち、個人コレクションとして残っているのは300点以下です。

-

現在、個人コレクションとして所有されているオキーフの絵画の多くは、時代の流れとともに美術館に遺贈され、その数はごくわずかとなっています。

- オキーフがアビキューのコットンウッドツリーを最初に描いたのは、1943年から1945年までのわずか2年間で、このコア・シリーズのために制作した作品はほんの一握りでした。この「コットンウッドツリー」シリーズの作品の多くは、現在、バトラー美術館やブルックリン美術館などの美術館に所蔵されています。

美術館所蔵の「綿の木」「樹木」「アビキュー」の絵

ジョージア・オキーフ美術館、サンタフェ

サンタバーバラ美術館

ジョージア・オキーフ美術館、サンタフェ

バトラー・インスティテュート・オブ・アメリカン・アート(オハイオ州

ジョージア・オキーフ美術館、サンタフェ

クリーブランド美術館

ダラス美術館

ニューメキシコ美術館(サンタフェ

ボストン美術館

ブルックリン美術館(ニューヨーク

メトロポリタン美術館(ニューヨーク)

ホイットニー美術館(ニューヨーク)

ジョージア・オキーフ美術館、サンタフェ

クリーブランド美術館

シカゴ美術館

イメージギャラリー

追加リソース

認証

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), New Mexico, 1943 は、Barbara Buhler Lynes による Georgia O'Keeffe の作品カタログレゾネで1066番として掲載されています。この絵は第2巻の670ページに図版が掲載されています。

カタログレゾネを見る

お 問い合わせ

こちらもご覧ください