Rejoignez-nous pour une visite vidéo de notre galerie de Jackson Hole, Wyoming, qui présente des œuvres de Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Elaine de Kooning et Willem de Kooning, entre autres.

LES ŒUVRES D'ART ACTUELLEMENT EXPOSÉES À HEATHER JAMES JACKSON HOLE

Expositions dignes d'intérêt

MERVEILLES DE L'ART IMPRESSIONNISTE ET MODERNE EN AMÉRIQUE ET EN EUROPE

EDOUARD HOPPER

LES PEINTURES DE SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL

NORMAN ROCKWELL : L'ARTISTE AU TRAVAIL

Contactez-nous

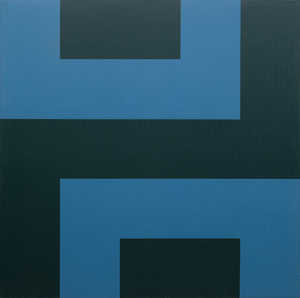

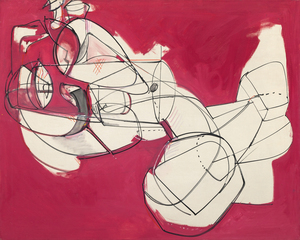

_tn43950.jpg )

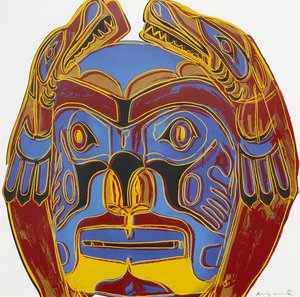

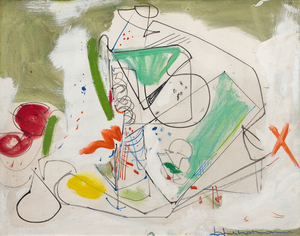

_tn46616.jpg )

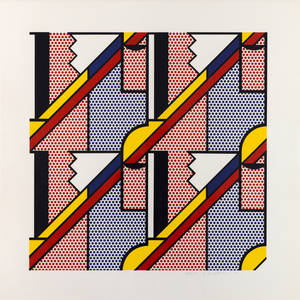

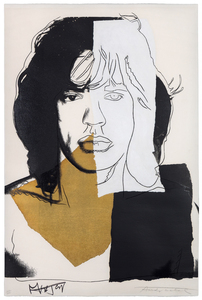

_tn47464.jpg )