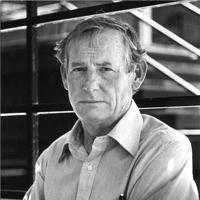

WAYNE THIEBAUD (1920-2021)

Wayne Thiebaud became an American icon as the artist who dragged thick layers of paint across canvases, depicting still-life cakes and desserts. He also painted large-scale portraits, Northern California landscapes, and San Francisco cityscapes, where streets become vertiginous exercises in geometric abstraction.

Wayne Thiebaud became an American icon as the artist who dragged thick layers of paint across canvases, depicting still-life cakes and desserts. He also painted large-scale portraits, Northern California landscapes, and San Francisco cityscapes, where streets become vertiginous exercises in geometric abstraction.

While living briefly in New York in the late 1950s, Thiebaud became friends with Abstract Expressionist painters including Elaine and Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. The artist spent much of his childhood in Long Beach, California, the subject of a series of paintings that he populated with bathers. This theme permeates art history, from Paul Cezanne to David Hockney.

Thiebaud’s paintings capture a distinctly coastal experience, with a Utopian sensibility and idyllic landscapes in which figures play and relax on the soft sand, amid crashing waves on the dreamy coastline. In 2007, a survey exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum emphasized the artist’s life on the California coast; it was an autobiographical pursuit that underscored the show’s title American Memories. Likewise, the show focused on Thiebaud’s vast body of work and his stylistic changes that punctuated different time periods.