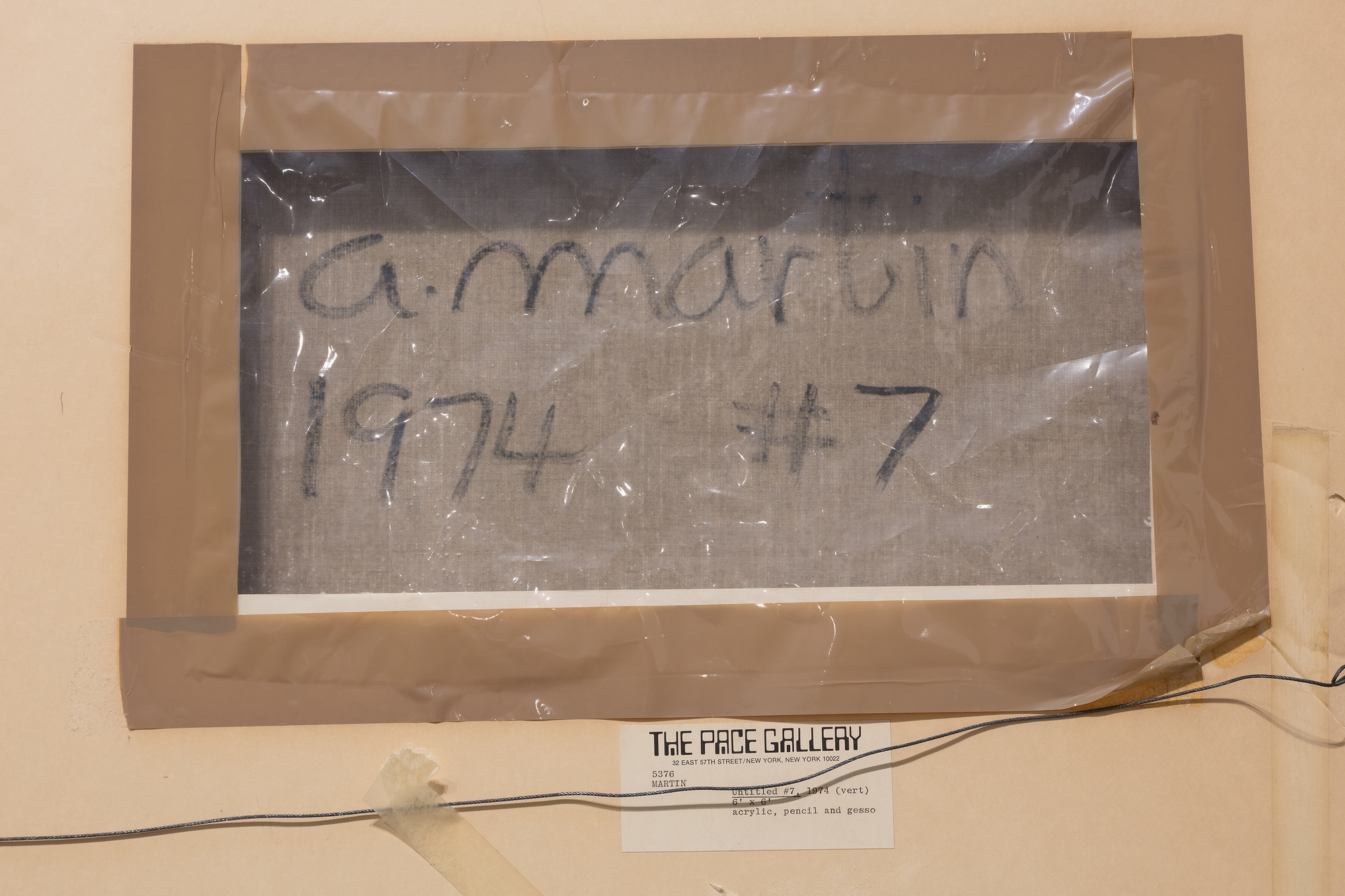

AGNES MARTIN (1912-2004)

Provenance

Pace Gallery, New YorkHelen W. Benjamin, New York

Sotheby's New York, May 8, 1996, lot 50

Private Collection, United States

Ace Gallery, Los Angeles

Private Collection, acquired from the above, May 1998

Exhibition

New York, Pace Gallery, Agnes Martin: New Paintings, 1975Literature

Beeren, W.A.L., Bloem, M. (1991), Agnes Martin: Paintings and Drawings 1974-1990, Stedelijk Museum. p. 62 (illustrated)Bell, T., Agnes Martin Catalogue Raisonné : Paintings [Online], Cahier’s d’Art Institute

Gruen, J. (September 1976), "...More...Agnes Martin: 'Everything, every thing is about feeling...feeling and recognition’” Artnews, p. 91, illustrated in color

Gula, K. (May - June 1975), "Review of Exhibitions: Agnes Martin at Pace," Art in America 63, p. 85, illustrated in color

...LESS...

IMPORTANT FACTS

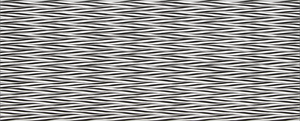

- While we may often see her horizontal stripes and grids, Martin’s oeuvre is much more varied particularly in earlier decades when her output was more experimental. The vertical stripes make this painting particularly special and historically important.

- Of the 639 paintings Martin made during her lifetime, only 34 feature vertical stripes, making this painting exceedingly rare. 1974 was also a very important year for Martin, marking her return to painting after a sabbatical.

- The record for a Martin painting at auction was set in 2023 when Grey Stone II (1961) sold for $18,718,500 USD. The top 5 Martin paintings at auction all sold for over $6 million USD.

- A recent resurgence of interest in artwork by women adds value to this piece as major museums seek to highlight historically marginalized groups. Martin created just 568 paintings in her prime period between 1960-2004. Of those, 145 are held in permanent museum collections, leaving 423 that might become available for sale.

Agnes Martin

Taos, New Mexico, circa 1953

History

When Agnes Martin returned to painting in 1974 after a seven-year hiatus, she brought not a sense of reinvention but of quiet certainty. The hiatus had been profound — a self-imposed silence after years of searching, waiting and listening. And when the time came to pick up the brush again, it was not with ambition or novelty but with clarity. “You have to practice a quiet, empty mind,” she insisted. “You don’t have to make any effort. You have to really want it, not change your mind.”

That, for Martin, was the condition of inspiration — and of art. The artist who claimed the best moments of her life were spent alone in silence also understood the profound companionship of beauty. To her, beauty was “the mystery of life,” not something seen but something known in the mind — a signal of perfection, a stillness independent of explanation. Her home in New Mexico, where the plains stretched infinitely in every direction, gave her a model for this kind of space: expansive, linear, and indivisible.

The present work., titled No. 7, completed in that pivotal year, is among Martin’s first works after her long period of waiting. Seven alternating vertical bands of pale blue and an almost indeterminate blushed tone, each rendered in delicate washes over a white gesso ground, No. 7 is compelling not for what it depicts but for the atmosphere it evokes, surrendering to serenity over spectacle, rhythm over representation, and taken as a whole, worthy of meditations on Martin’s skill as one of the most sensitive colorists of her time.

Any close examination of a blue band reveals a surface quietly alive with movement. Martin applied the paint in transparent layers, the pigment settling like shimmery sheets of water on glass. She thinned the medium to a watery consistency yet maintained perfect control, halting the flow before it could wander. This balance — between liquidity and discipline — gives the work an immanent presence: luminous, rhythmic, and utterly calming. Martin admired Barnett Newman immensely, and it is tempting to compare Rothko’s internal light to Barnett Newman’s vertical “zips.” But where Newman’s lines often feel like thunderbolts dividing the void, Martin’s dissolve into it. Her paintings do not demand transcendence; they whisper of it.

The warmer hue, soft and veil-like, is not unlike a pressed powder used to balance a complexion — barely pigmented, yet quietly transformative. Suffused with a gentle warmth, it registers elements of pink, but perhaps only in relation to the cooler bands beside it. This subtle dialogue between hues is where Martin’s color work becomes poetic: what seems restrained in isolation achieves radiance through adjacency. The tonal equivalence between hues creates a low-frequency luminosity as if light were softly pulsing beneath the surface. The result is as much musical as visual — an internal rhythm, a hum. One critic observed that the palette feels “bright and clean without being overtly naturalistic or artificially lurid” and that understated balance gives the work its lasting power.

Martin’s technique proved as meditative as her philosophy. She painted slowly and with discipline, always beginning with a mental image and then transcribing it with exacting care. Lines were drawn with a short ruler — never a long one, lest the canvas sag — and she prepared tapes marked with exact measurements, inscribing each band with pencil, faint enough to be barely visible under the soft pastel washes of paint. The result was an illusion of weightlessness. Traces of the underdrawing remain — not as flaws, but as the record of a human hand seeking precision without force.

In the years following her return, Martin often spoke of inspiration as visiting only those who wait without expectation — who clear the mind of facts, theories, and ego. “If your mind is full of facts,” she said, “you wouldn’t recognize it anyway if an inspiration came.” Her working method, life, and art all orbited around the radical practice of abandoning ambition, relinquishing control, and cultivating trust, not just in her materials but in the mysterious order of things.

Martin lived a life shaped by solitude, not loneliness. Her return to painting in 1974 marked not a reinvention but a reaffirmation — and No. 7, one of the first works from that period, is emblematic of the serene discipline and inward gaze that defined her second act as a painter. She continued to paint vertical and horizontal bands, each new work a variation on stillness, each a reminder that simplicity is not an absence but a culmination. From that point forward, her art became less about painting and more about presence — about offering the viewer a resting place for the mind.

Agnes Martin photographed in her studio by Mildred Tolbert / c.1955 © the Mildred Tolbert Archive Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos

TOP PAINTINGS SOLD AT AUCTION

Paintings in Museum Collections

© 2025 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

© 2016 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Inquire

You May Also Like

_tn47012.jpg )

_tn31465.b.jpg )

_tn27843.jpg )

_tn46214.jpg )

_tn39239.jpg )

_tn47464.jpg )

_tn46213.jpg )

_tn27989.jpg )

_tn47033.jpg )

_kuwayama_b-139_tn16773.b.jpg )

_tn22479.jpg )