LEE KRASNER (1908-1984)

$195,000

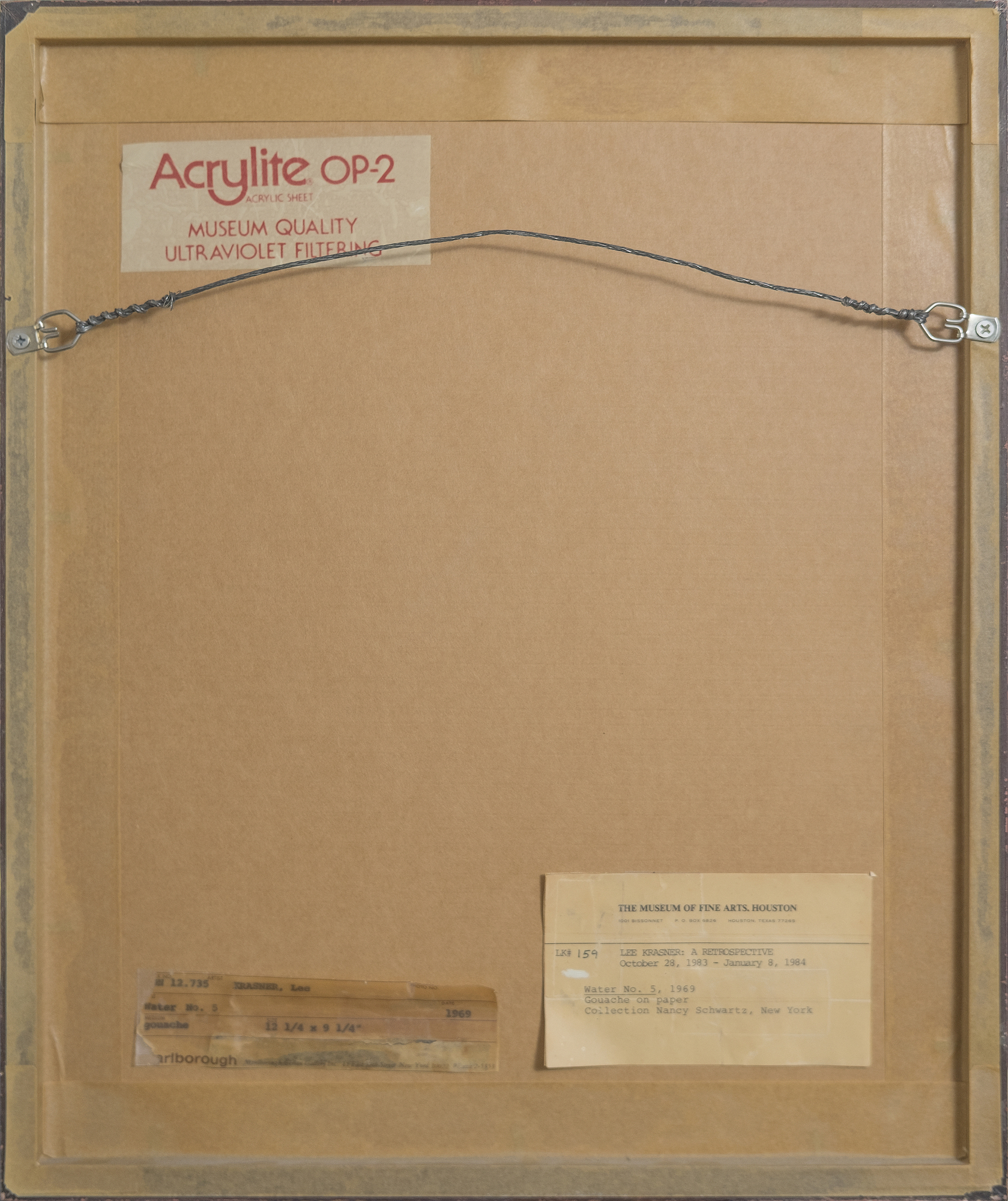

Provenienz

Marlborough-GaleriePrivatsammlung, erworben von der oben genannten Person, um 1970

Privatsammlung

Literaturhinweise

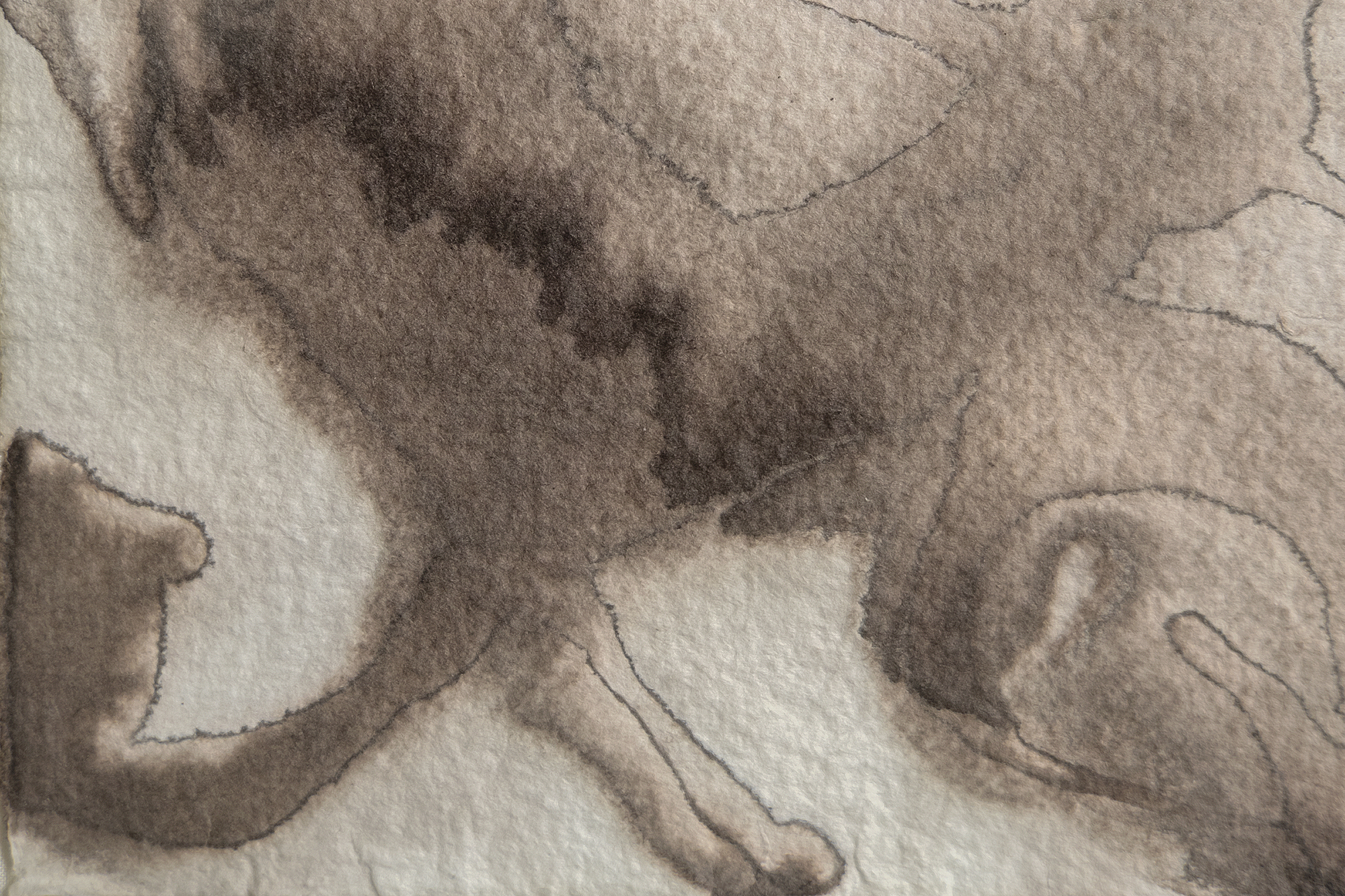

Landau, Ellen G., Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné, New York: Abrams, 1995, S. 254, illus. 511Als "Gouache auf Papier" katalogisiert, lässt die offensichtliche Transparenz in Werken wie "Water No. 5" darauf schließen, dass Krasner traditionelle Aquarelltechniken verwendete, um die dichteren, undurchsichtigen Effekte zu erzielen, die oft mit Gouache in Verbindung gebracht werden. Künstler können eine solche Opazität mit Aquarellfarben erreichen, indem sie das Pigment-Wasser-Verhältnis erhöhen, durchscheinende Lavierungen schichten, um Tiefe zu erzeugen, oder Pigmente verwenden, die von Natur aus zu Granulation und Sättigung neigen. Krasners Wahl des Howell-Papiers, das für seine mittelgroben "Zähne" bekannt ist, verstärkte diese Effekte ebenfalls, da seine Textur das Licht streut und den Pigmenten ein festeres Aussehen verleiht. Diese Techniken zeigen Krasners Beherrschung ihrer Materialien und ihre intuitive, praktische Herangehensweise an das Experimentieren, die es ihr ermöglichte, die Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten der Aquarellmalerei zu erweitern, ohne sich ausschließlich auf Gouache zu verlassen.

Krasner war nicht die einzige, die sich von der Landschaft von Long Island inspirieren ließ. Ihr Nachbar Willem de Kooning reagierte in ähnlicher Weise auf die Vitalität der Küste und übertrug ihre wogenden Rhythmen in sein Werk der 1960er Jahre. Krasner hingegen verzichtet in der "Water"-Serie auf figurative Bezüge und stützt sich allein auf ihre Fähigkeit, die transformative Energie der Natur durch Abstraktion einzufangen. Mit "Water No. 5" gelang Krasner eine tiefgreifende Synthese von Technik und Vision, die die meditative Kraft ihrer Umgebung mit der dynamischen Energie ihrer künstlerischen Praxis verschmolz und ihre Position als bahnbrechende Kraft der amerikanischen Nachkriegskunst unterstrich.