לי קרסנר (1908-1984)

$195,000

מקור ומקור

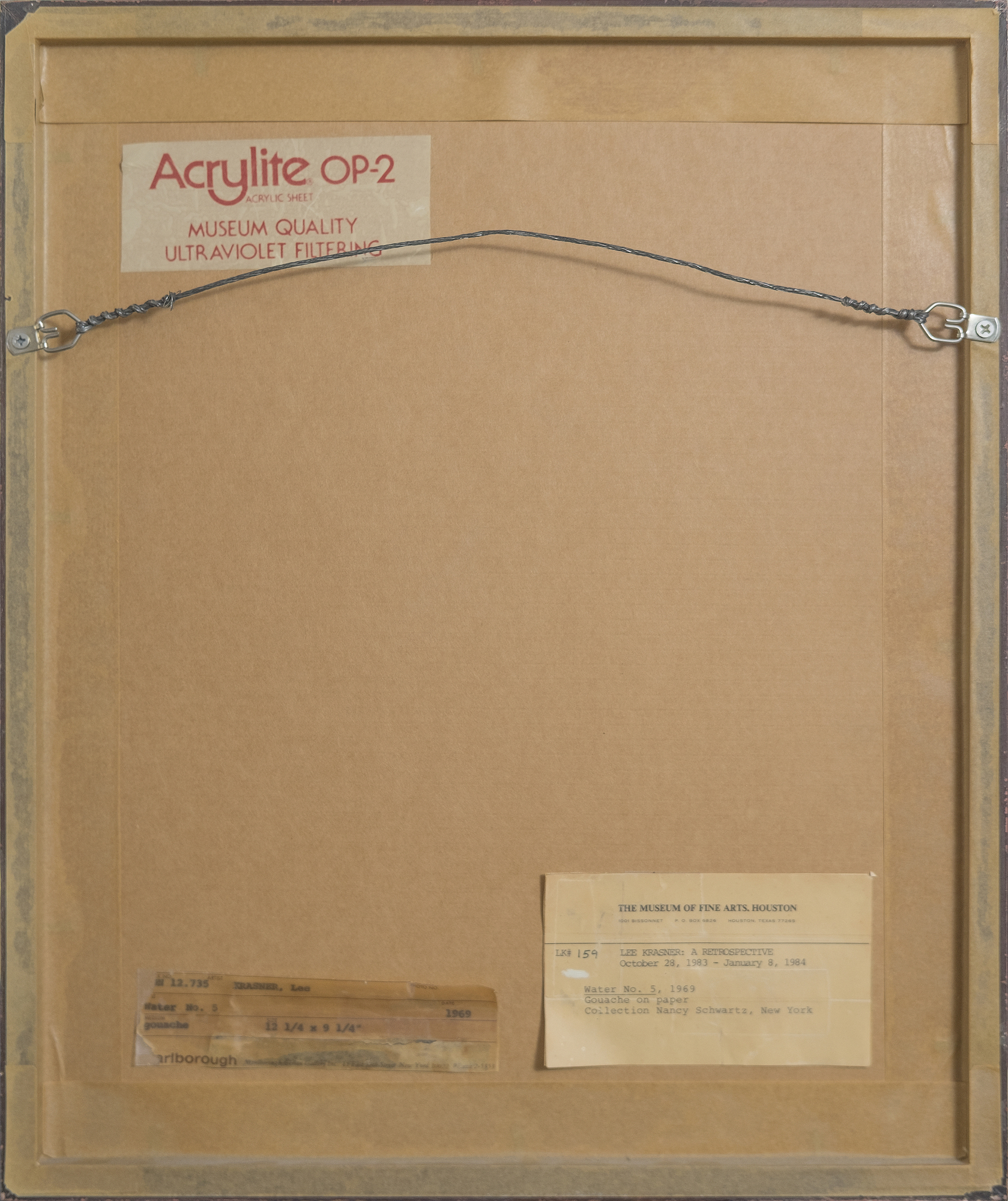

גלריית מרלבורואוסף פרטי, נרכש מהאמור לעיל, ג. 1970

אוסף פרטי

ספרות

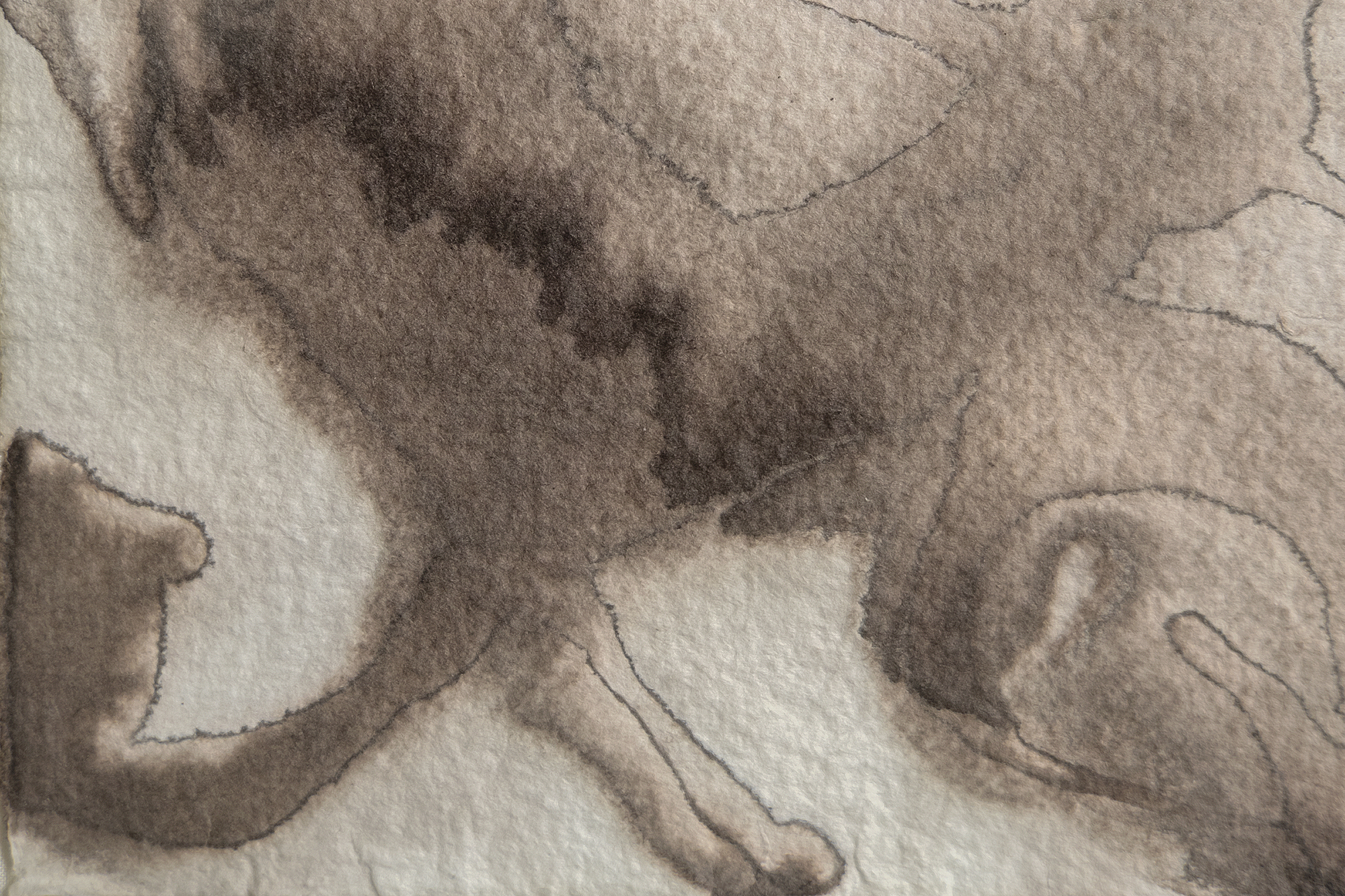

Landau, Ellen G., Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné, New York: Abrams, 1995, p. 254, אשליה. 511שקיפות הפטנט בעבודות כמו "מים מס' 5", שקוטלגה כ"גואש על הנייר", מעידה על כך שקרסנר השתמש בטכניקות צבעי מים מסורתיות כדי ליצור את האפקטים הדחוסים והאטומים יותר הקשורים לעתים קרובות לגואש. אמנים יכולים להשיג אטימות כזו בצבעי מים על ידי הגדלת יחס הפיגמנט למים, ריבוי שטיפות שקופות לשכבות לעומק, או שימוש בפיגמנטים המועדים באופן טבעי לגרנולציה ורוויה. הבחירה של קרסנר בנייר האוול, הידוע ב"שן הבינונית עד הגסה" שלו, הגבירה גם את ההשפעות הללו, שכן המרקם שלו מפזר אור כדי להעניק לפיגמנטים מראה מוצק יותר. טכניקות אלו מדגימות את שליטתה של קרסנר בחומרים שלה ואת הגישה האינטואיטיבית והמעשית שלה לניסויים, ומאפשרות לה להרחיב את אפשרויות הביטוי של צבעי מים מבלי להסתמך רק על גואש.

קרסנר לא היה לבד בחיפוש אחר השראה בנוף של לונג איילנד. שכנה, וילם דה קונינג, הגיב באופן דומה לחיוניותו של קו החוף, ותרגם את מקצביו המתגלגלים לעבודותיו משנות ה-60. אולם עבור קרסנר, לסדרת "מים" אין התייחסויות פיגורטיביות, הנשענות אך ורק על יכולתה ללכוד את האנרגיה הטרנספורמטיבית של הטבע באמצעות הפשטה. עם "מים מס' 5", קרסנר השיגה סינתזה עמוקה של טכניקה וחזון, תוך מיזוג הכוח המדיטטיבי של סביבתה עם האנרגיה הדינמית של העשייה האמנותית שלה, והדגיש את מעמדה ככוח חלוצה באמנות אמריקאית לאחר המלחמה.