リー・グラスナー(1908-1984)

$195,000

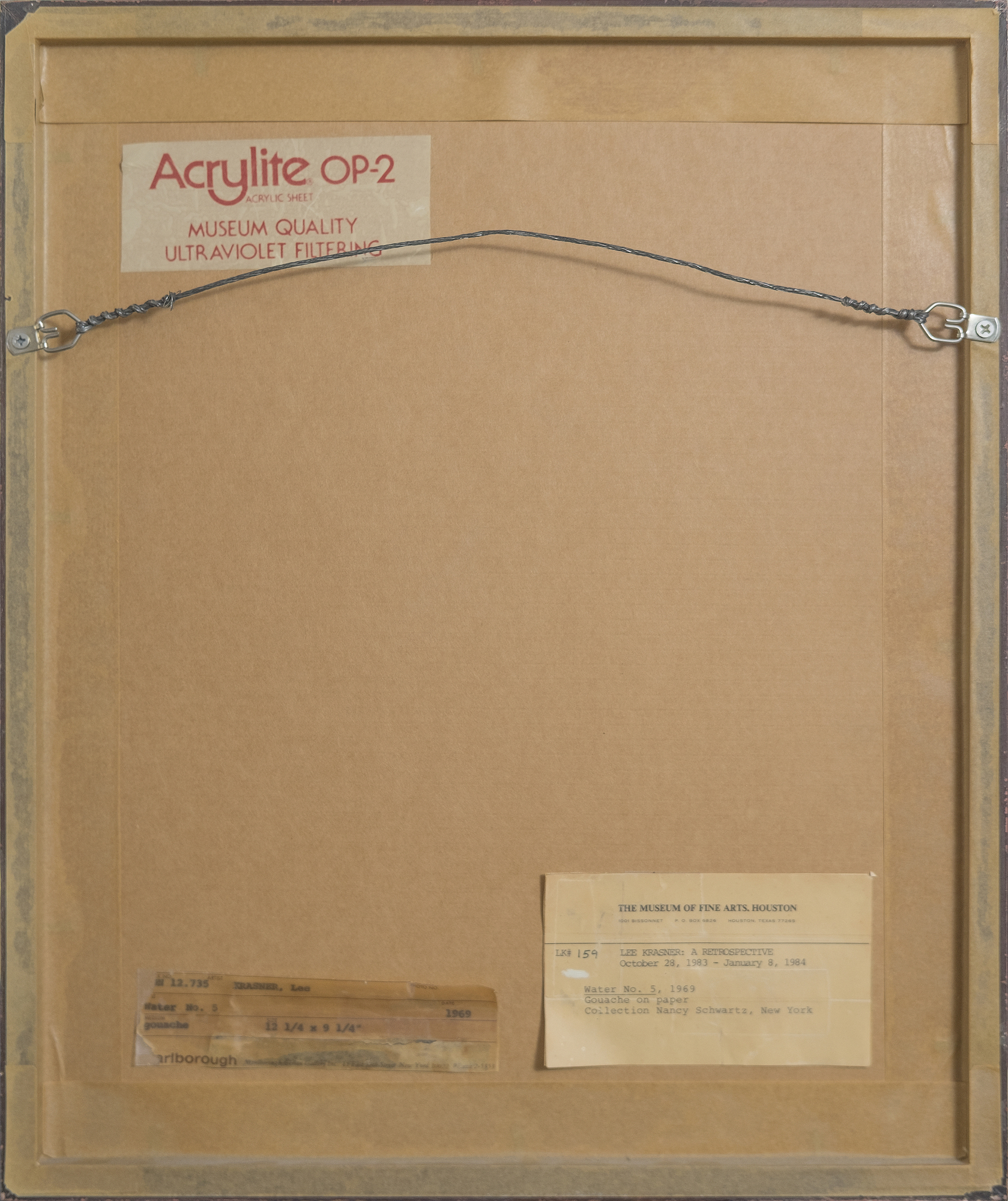

出所

マールボロ・ギャラリープライベート・コレクション、上記より入手、1970年頃

プライベート・コレクション

文学

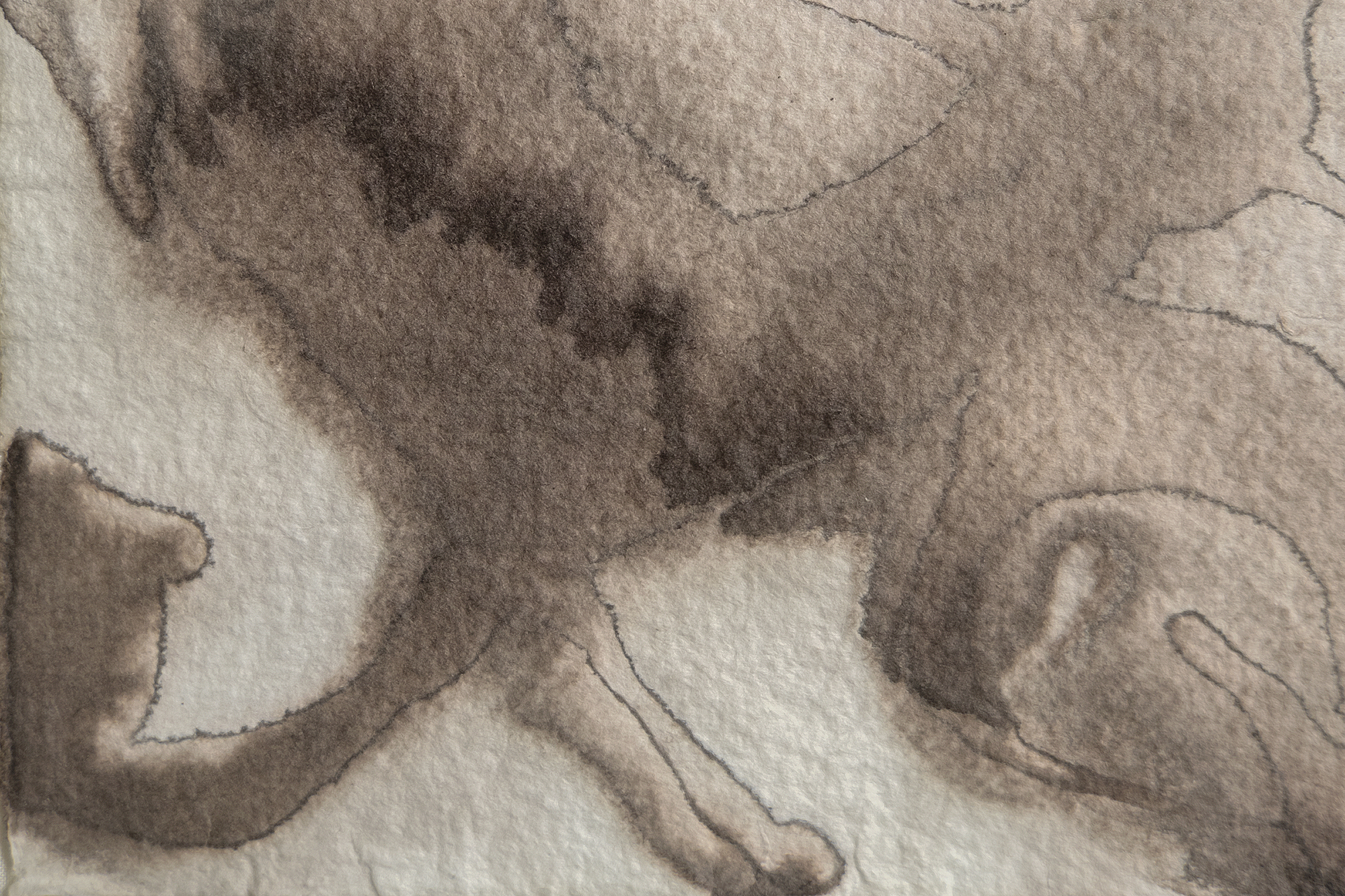

Landau, Ellen G., Lee Krasner:A Catalogue Raisonné, New York:エイブラムス、1995年、254頁、図版。511「紙にグワッシュ」とカタログに記されているが、「Water No.5」のような作品に見られるパテントのような透明感は、クラスナーが伝統的な水彩画の技法を用いて、グワッシュによく見られる濃密で不透明な効果を生み出したことを示唆している。水彩では、顔料と水の比率を高めたり、半透明のウォッシュを重ねて深みを出したり、もともと粒状化や飽和を起こしやすい顔料を使ったりすることで、このような不透明感を出すことができる。クラスナーが選んだハウエル紙は、中程度に粗い「歯」で知られ、その質感が光を散乱させて顔料をより堅固に見せるため、こうした効果も高めた。これらの技法は、クラスナーの素材に対する熟練度と、実験に対する直感的で実践的なアプローチを示しており、彼女はガッシュだけに頼ることなく、水彩画の表現の可能性を広げることができた。

ロングアイランドの風景にインスピレーションを見出したのはクラスナーだけではない。彼女の隣人であるウィレム・デ・クーニングも同様に、海岸線の生命力に反応し、そのうねるようなリズムを1960年代の作品に反映させた。しかし、クラスナーの場合、「水」シリーズは具象的な参照を欠き、抽象化によって自然の変容するエネルギーをとらえる能力にのみ頼っている。水 No.5」で、クラスナーは技法とヴィジョンの深遠な統合を達成し、周囲の瞑想的な力と芸術的実践のダイナミックなエネルギーを融合させ、戦後アメリカ美術のパイオニアとしての地位を明確にした。