LEE KRASNER (1908-1984)

$195,000

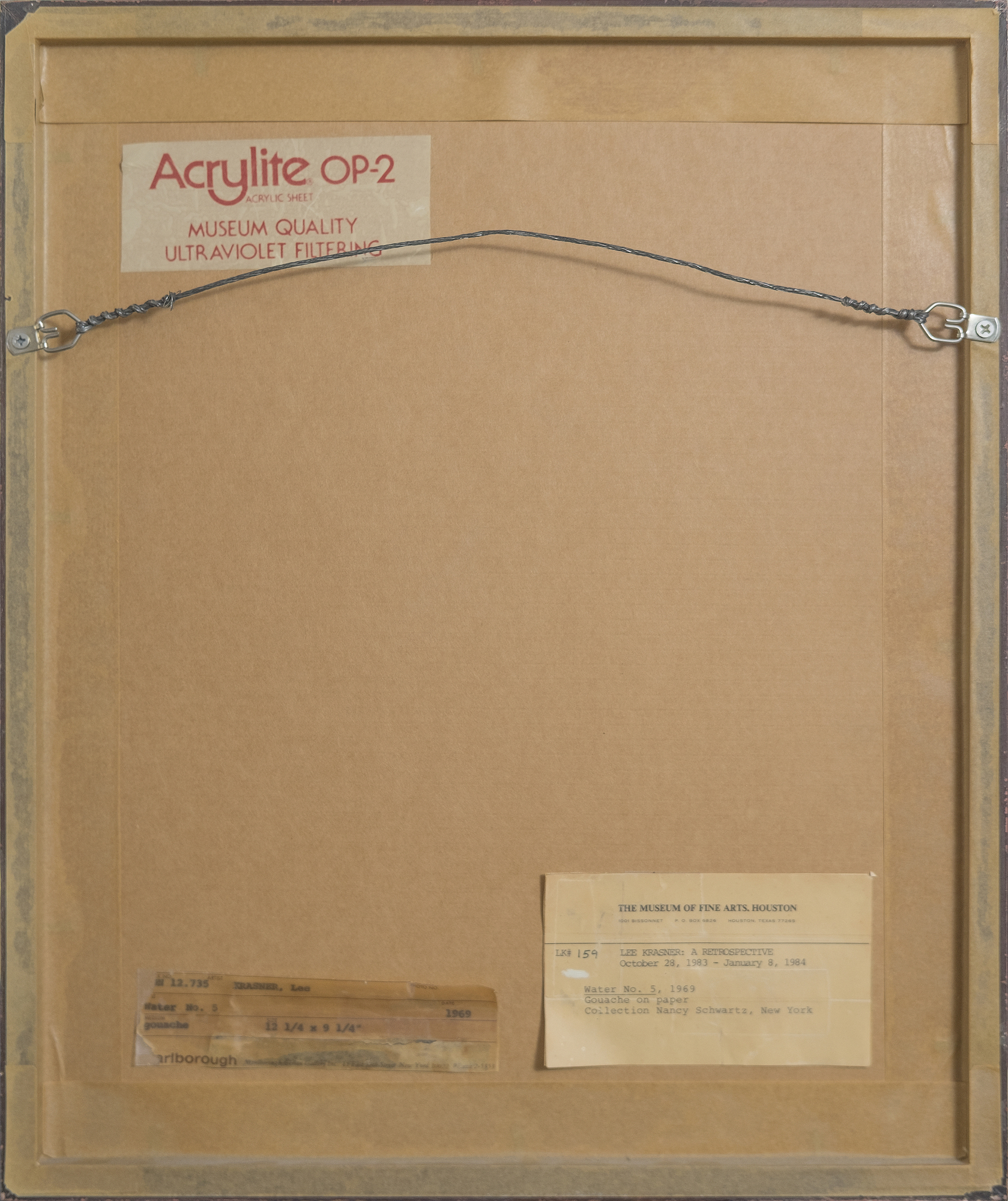

Procedencia

Galería MarlboroughColección privada, adquirida a la anterior, c. 1970

Colección privada

Literatura

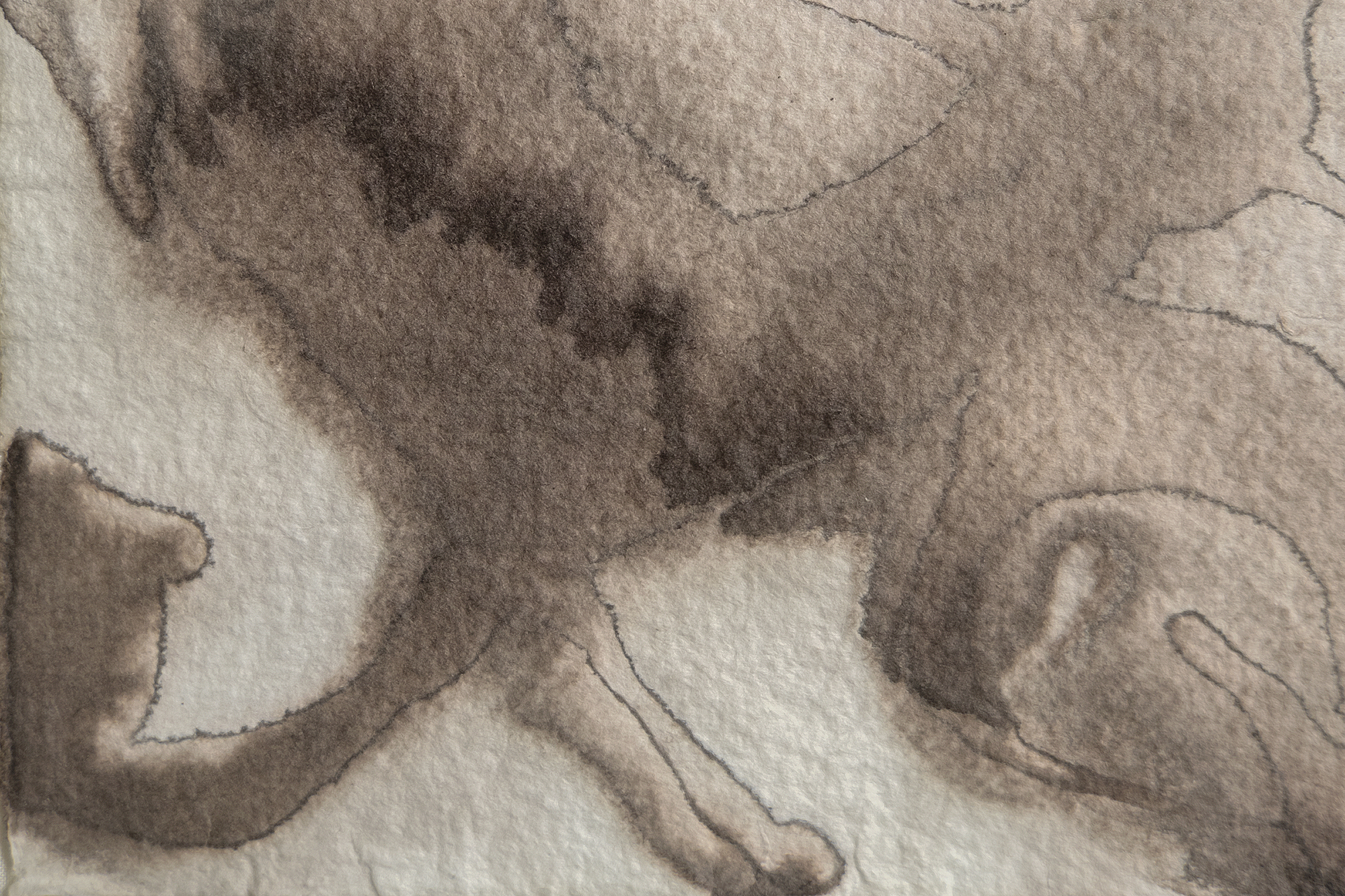

Landau, Ellen G., Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné, Nueva York: Abrams, 1995, p. 254, illus. 511Catalogada como "gouache sobre papel", la patente transparencia de obras como "Agua n.º 5" sugiere que Krasner utilizó técnicas tradicionales de acuarela para crear los efectos más densos y opacos que suelen asociarse al gouache. Los artistas pueden lograr esa opacidad en la acuarela aumentando la proporción pigmento-agua, superponiendo lavados translúcidos para dar profundidad o utilizando pigmentos naturalmente propensos a la granulación y la saturación. El papel Howell elegido por Krasner, conocido por su "dentado" medio a áspero, también potenciaba estos efectos, ya que su textura dispersa la luz para dar a los pigmentos un aspecto más sólido. Estas técnicas demuestran el dominio de Krasner de sus materiales y su enfoque intuitivo y práctico de la experimentación, lo que le permitió ampliar las posibilidades expresivas de la acuarela sin depender únicamente del gouache.

Krasner no era la única que encontraba inspiración en el paisaje de Long Island. Su vecino, Willem de Kooning, también respondió a la vitalidad de la costa, plasmando sus ritmos ondulantes en su obra de los años sesenta. Para Krasner, sin embargo, la serie "Agua" carece de referencias figurativas y se basa únicamente en su habilidad para captar la energía transformadora de la naturaleza a través de la abstracción. Con "Agua nº 5", Krasner logró una profunda síntesis de técnica y visión, fusionando el poder meditativo de su entorno con la energía dinámica de su práctica artística, subrayando su posición como fuerza pionera en el arte estadounidense de posguerra.