Unsere Galerie in Palm Desert liegt zentral im kalifornischen Palm Springs, angrenzend an den beliebten Einkaufs- und Essbereich von El Paseo. Unsere Kundschaft schätzt unsere Auswahl an Nachkriegs-, Moderner- und Zeitgenössischer Kunst. Das herrliche Wetter in den Wintermonaten zieht Besucher aus der ganzen Welt an, um unsere schöne Wüste zu sehen und in unserer Galerie vorbeizuschauen. Die bergige Wüstenlandschaft im Freien bietet die perfekte landschaftliche Kulisse für das visuelle Fest, das im Inneren erwartet.

45188 Portola Avenue

Palm Desert, CA 92260

(760) 346-8926

Öffnungszeiten:

Nur nach Vereinbarung - bis 15. Oktober 2024

Ausstellungen

AKTUELL

Kein anderes Land: Ein Jahrhundert amerikanischer Landschaften

AKTUELL

Alexander Calder: Die Gestaltung eines primären Universums

AKTUELL

Georgia O'Keeffe und Ansel Adams: Moderne Kunst, moderne Freundschaft

AKTUELL

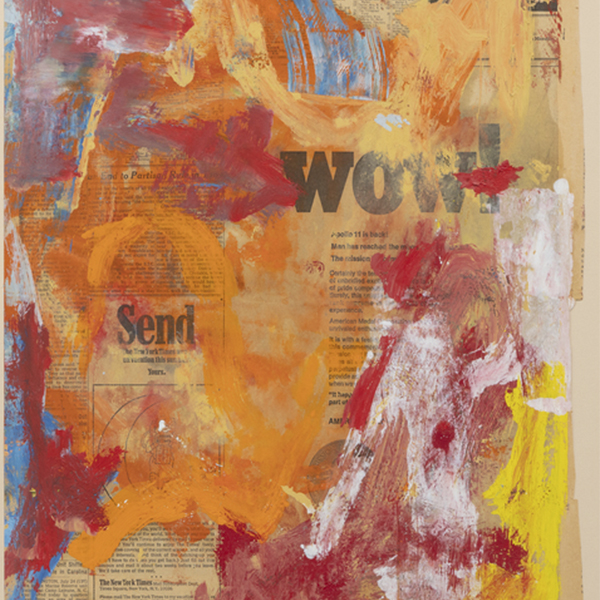

Das Blut deines Herzens: Überschneidungen von Kunst und Literatur

AKTUELL

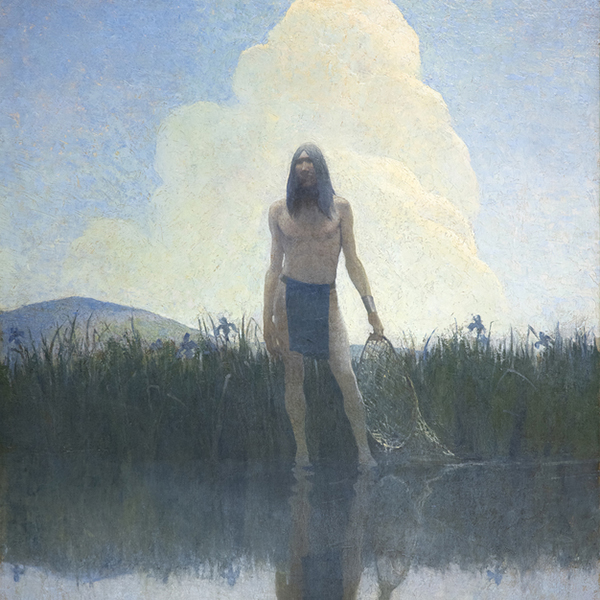

Dem Leben begegnen: N.C. Wyeth und die MetLife-Wandmalereien

ARCHIV

Mehr zum Leben: Impressionistische Dialoge von Monet und darüber hinaus

ARCHIV

Jüdische Moderne Teil 2: Figuration von Chagall bis Norman

ARCHIV

Vincent van Gogh und die großen Impressionisten des Grand Boulevard

ARCHIV

Ferrari und Zukunftsforscher: Ein italienischer Blick auf die Geschwindigkeit

KUNSTWERKE ZUR ANSICHT

IN DEN NACHRICHTEN

DIENSTLEISTUNGEN

Heather James Fine Art bietet eine breite Palette von kundenorientierten Dienstleistungen, die auf Ihre spezifischen Bedürfnisse zugeschnitten sind. Unser Operations-Team besteht aus professionellen Kunsthändlern, einer kompletten Registrierungsabteilung und einem Logistikteam mit umfangreicher Erfahrung im Bereich Kunsttransport, Installation und Sammlungsmanagement. Mit einem weißen Handschuhservice und einer persönlichen Betreuung geht unser Team noch einen Schritt weiter, um unseren Kunden außergewöhnliche Kunstleistungen zu bieten.

_tn43950.jpg )

_tn27035.jpg )

_tn45106.jpg )

_tn27843.jpg )

_tn28596.jpg )

_tn40803.jpg )

_tn36185.jpg )

_tn37425.jpg )

,_new_mexico_tn40147.jpg )

_tn45742.jpg )

_tn45741.jpg )

_tn45731.jpg )

_tn45733.jpg )

_tn45732.jpg )

_tn45736.jpg )