ALFRED SISLEY (1839-1899)

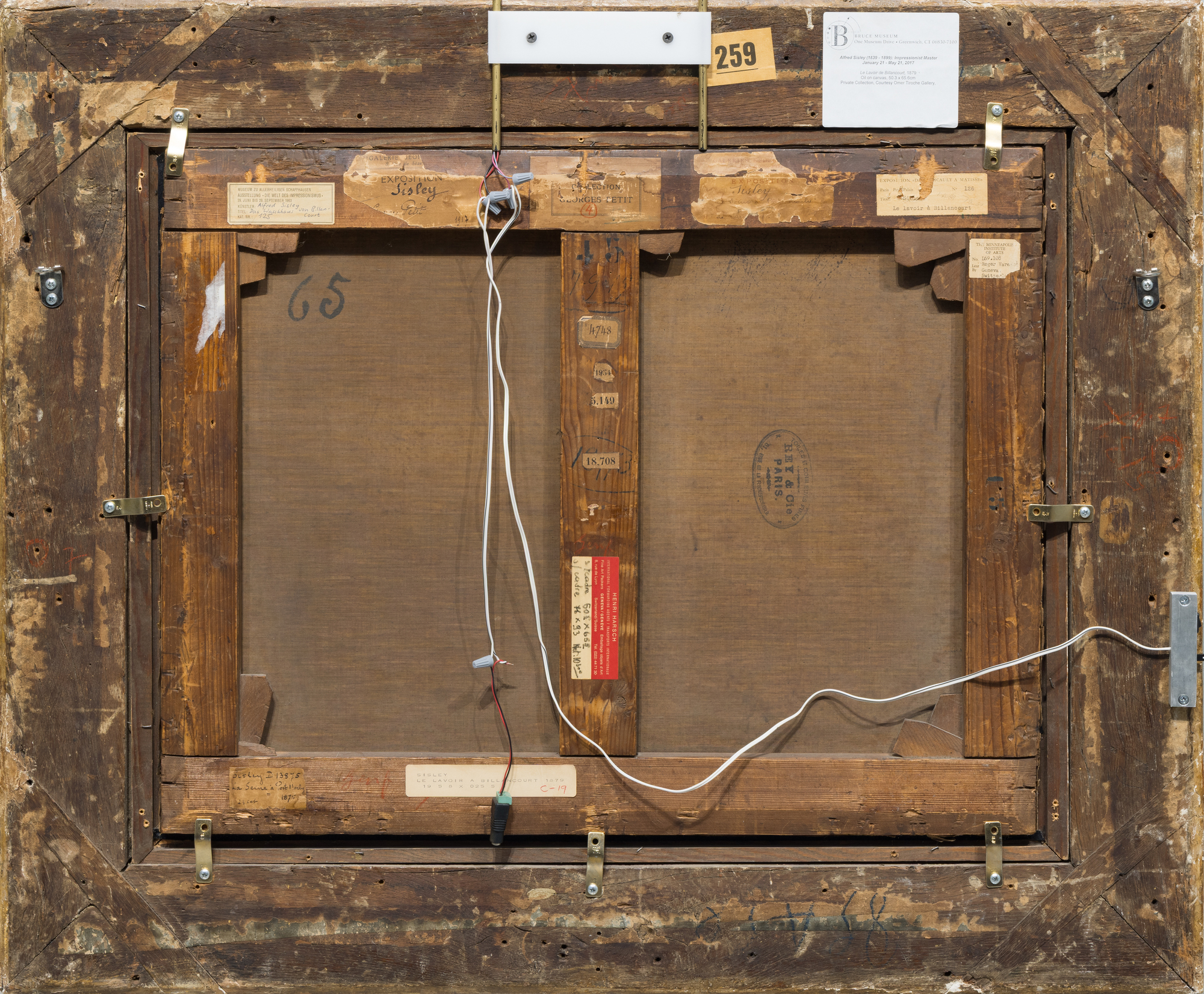

Provenance

Henri Poidatz, ParisGalerie Georges Petit, Paris, April 27, 1900, lot 79

Georges Petit, acquired at the above sale

Sale: Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, March 4-5, 1921, lot 113

Comte de Lanscay, Paris

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, April 6, 1922, lot 16

Eugène Blot, Paris, acquired at the above sale

Dr. Arthur Charpentier, Paris

Private Collection, Switzerland, acquired c. 1950

Private Collection, by descent from the above

Private Collection, Europe

Sotheby's New York, May 6, 2015, lot ...More...250

Private Collection, London, acquired at the above sale

Exhibition

Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, Alfred Sisley, 1917, no. 83Paris, Durand-Ruel, Tableaux de Sisley, 1930, no. 23

Paris, Galerie d'Art Braun, Sisley, 1933, no. 13

Berne, Kunstmuseum, Alfred Sisley, 1958, no. 38

Paris, Musée du Petit-Palais, De Gericault à Matisse, Chefs-d'oeuvre des collections Suisse, 1959, no. 126

Schaffhausen, Museum Zu Allerheiligen, Die Welt des Impressionnismus, 1963, no. 125

Minneapolis, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Past Rediscovered: French Painting 1800-1900, 1969

Literature

Maximilien Gauthier, "Hommage à Sisley," in L'Art vivant, 1933, no. 170, p. 116 (illustrated)François Daulte, Alfred Sisley, Catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint, Paris, 1959, no. 315 (illustrated)

Jacques Lassaigne & Slyvie Gache-Patin, Sisley, Paris, 1982, p. 31 (illustrated)

Mary Anne Stevens, ed., Alfred Sisley, London, 1992, p. 154

Sylvie Brame & François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue Critique des Peintures et des Pastels, Paris, 2021, p. 155, 488 (illustrated)

...LESS...

Painted along the Seine at Billancourt—an industrial town west of Paris—this work belongs to the sequence of views Sisley produced after the upheavals of 1871, when he moved his family first to Louveciennes and later to nearby Marly-le-Roi. The Seine valley offered him an ever-renewing motif: looping river bends, villages threaded along the banks, and a landscape marked by both history and modern life. Here, the floating washing house (a lavoir) sits low on the water, a practical structure where locals could wash clothes directly in the river for a small fee. Sisley transforms this everyday subject into an evocation of lived place, where human activity is integrated seamlessly into the broader rhythms of sky and current.

The 1870s are widely recognized as Sisley’s “golden period”—when his work speaks in a distinctly personal voice rather than under the overt influence of Corot, Courbet, or even early Monet. After ceasing to exhibit at the Salon after 1877, his compositions grew more complex and less dependent on traditional recession and linear perspective, shifting instead toward interlocking patterns and the expressive energy of his brushwork. In Le Lavoir de Billancourt, layers of pigment are built up in quick, multidirectional strokes, creating a richly textured surface saturated with color and air. This heightened spontaneity aligns with contemporary praise for Sisley’s ability to seize passing moments—clouds, breeze, and trembling foliage—so that space and light feel inseparable, and the scene remains vibrantly in motion. The painting is recorded in the François Dault Alfred Sisley: catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint (1959) as no. 315.