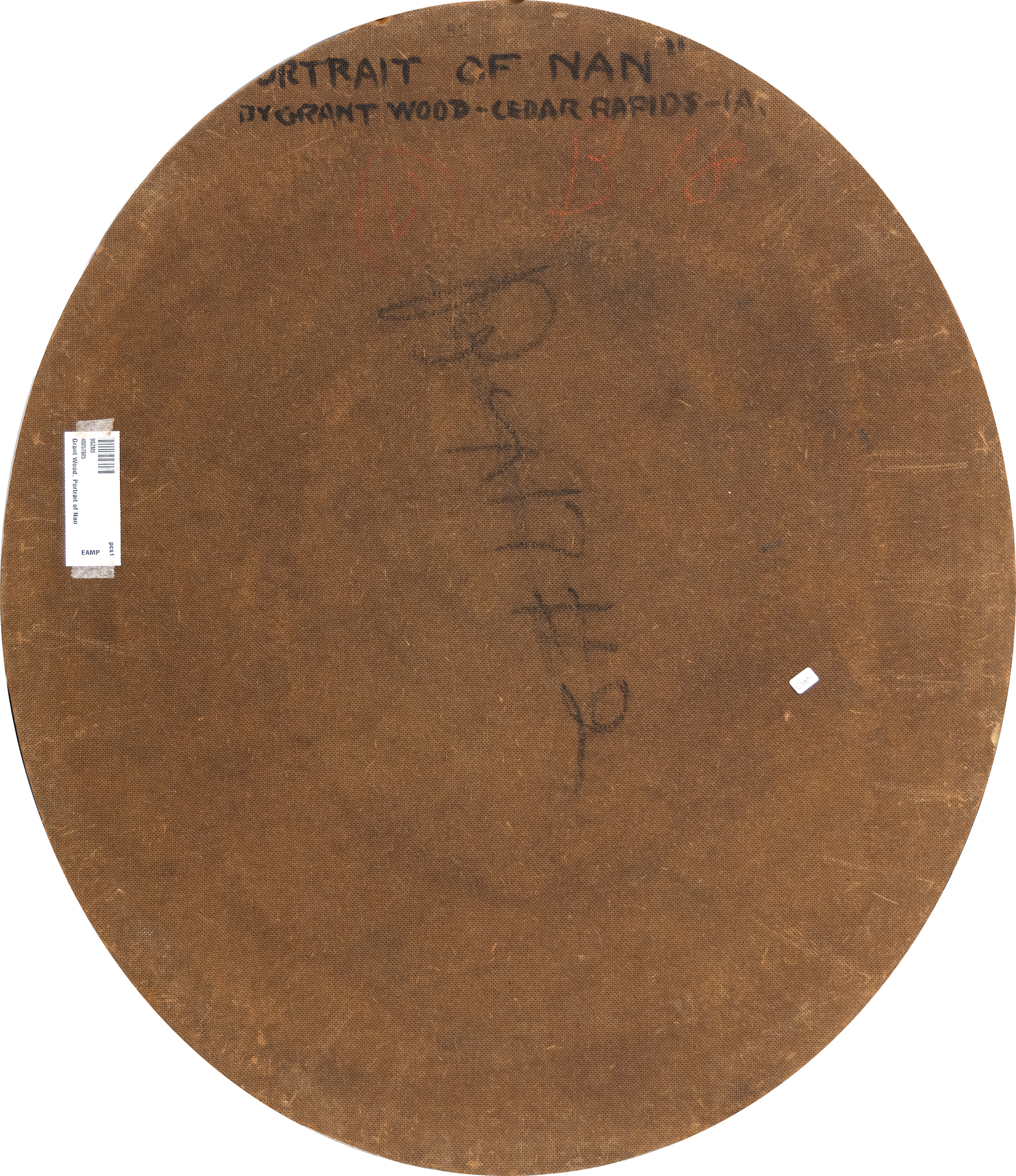

グラント・ウッド(1891-1942)

出所

ナン・ウッド・グラハム、1942年(グラント・ウッドの妹、子孫による)ブリタニカ百科事典コレクション、イリノイ州シカゴ、1945年、上記より入手

デュヴィーン・ギャラリーズ、ニューヨーク、1952年12月11日

ウィリアム・ベントン上院議員、ニューヨーク、サウスポート、コネティカット、上記より譲受

ヘレン・ボーリー、ウィスコンシン州マディソン、1973年(ウィリアム・ベントン上院議員の娘、子孫による)

2020年、現所有者が上記より譲り受ける

展示会

ネブラスカ州オマハ、ジョスリン・メモリアル、オープニング展示、1931年11月~12月イリノイ州シカゴ...もっとその。。。 1933年6月、グラント・ウッドの絵画展、ロビンソン・ギャラリーの増加

ニューヨーク、フェラルギル・ギャラリー、1934年6月

イリノイ州シカゴ、レイクサイド・プレス・ギャラリー、グラント・ウッド貸与素描・絵画展カタログ、1935年2月-3月

ニューヨーク、フェラルギル・ギャラリー、グラント・ウッドの絵画と素描展、1935年3月~4月

アイオワ・シティ、美術祭、アイオワ大学アイオワ・ユニオン・ラウンジ、グラント・ウッドとマーヴィン・D・コーンの絵画展、1939年7月

シカゴ、イリノイ州、シカゴ美術館、グラント・ウッド絵画・素描記念展、第53回アメリカ絵画・彫刻展、1942年10月-12月

シカゴ、イリノイ州、シカゴ美術館、ブリタニカ百科事典現代アメリカ絵画コレクション、1945年4月12日~5月13日

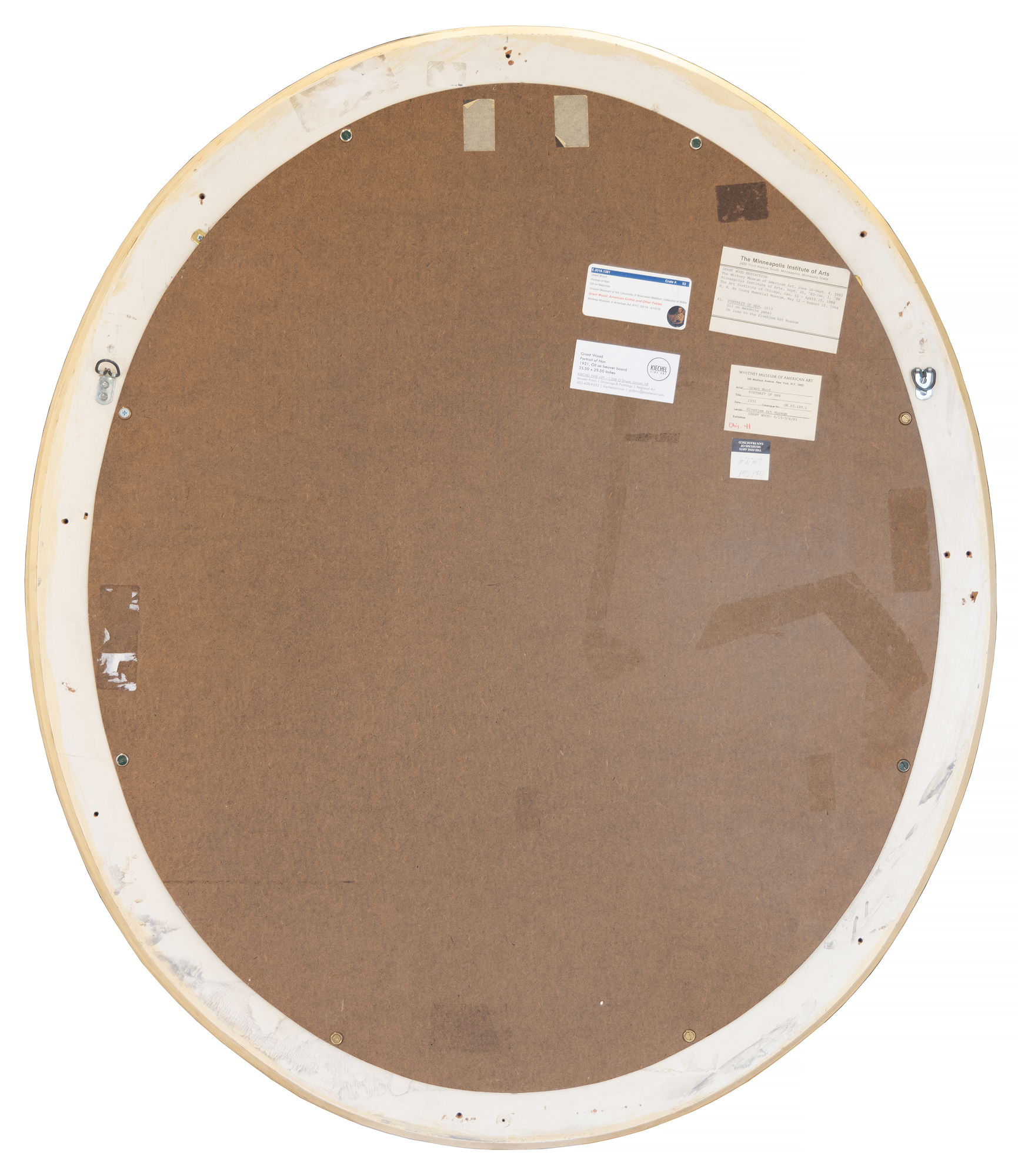

万国博覧会:ハートフォード、コネチカット、大阪、日本、ワズワース・アテネウム、ベントン・コレクション:20世紀アメリカの絵画、1971年3月~1月

ウィスコンシン州マディソン、ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校チャゼン美術館、1981年~2018年(長期貸出)

ホイットニー美術館(ニューヨーク)、ミネアポリス美術館(ミネソタ)、ミネアポリス美術館(シカゴ)、シカゴ美術館(イリノイ)、シカゴ美術館(サンフランシスコ)、M.H.デ・ヤング記念美術館「グラント・ウッド:リージョナリズムの展望」(1983-1984年

1991年2月~3月、アイオワ州ダベンポート、グラント・ウッド100周年記念式典&ナン・ウッド・メモリアル

ジョスリン美術館(ネブラスカ州オマハ)、ダベンポート美術館(アイオワ州ダベンポート)、ウスター美術館(マサチューセッツ州ウスター)、グラント・ウッド展:1995年12月~1996年12月「An American Master Revealed」展

コロンバス美術館(オハイオ州コロンバス)、ウィーン近代美術館/ルートヴィヒ財団(オーストリア、ウィーン)、ルートヴィヒ現代美術館(ハンガリー、ブダペスト)、マディソン・アート・センター(ウィスコンシン州マディソン)、スーフォールズ(サウスダコタ州スーフォールズ)、ワシントン芸術科学館「エデンの幻想」:2000年2月~2001年8月、アメリカン・ハートランドのヴィジョン展

アイオワ州シーダーラピッズ、シーダーラピッズ美術館、グラント・ウッド、5ターナー・アレイ、2006年9月~1月

ワシントンD.C.、スミソニアン・アメリカ美術館レンウィック・ギャラリー、グラント・ウッドのアトリエ:アメリカン・ゴシック発祥の地、2006年3月~7月

ホイットニー美術館、ニューヨーク、グラント・ウッド:アメリカン・ゴシックとその他の寓話」2018年3月~6月

フロリダ州ウェストパームビーチ、アン・ノートン・スカルプチャー・ガーデンズ、クリエイティビティの発見:アメリカン・アート・マスターズ、2024年1月10日〜3月17日

文学

コーン、W.M.(1985)、グラント・ウッド:地域主義者のビジョン、エール大学出版部、102ページ。Graham, N. W., Zug, J., & McDonald, J. (1993), My Brother, Grant Wood, State Historical Society of Iowa, p. 46, 106, 111-112, back cover.

Dennis, J.M. (1998), Renegade Regionalists:グラント・ウッド、トーマス・ハート・ベントン、ジョン・ステュアート・カリーの近代の独立』ウィスコンシン大学出版部、p. 106, 108

Milosch, J.C. (2005), Grant Wood's Studio:アメリカン・ゴシック発祥の地, シーダーラピッズ美術館, 19頁

グラント・ウッド、チャールズ・シーラー、ジョージ・H・デュリーに関する新たな視点』マロニーJ.(2010)、ガラ・ブックス、p.32、76-77

Evans, T. (2010), Grant Wood:A Life, ペンギン・ランダムハウス, p. 120-27, 302

テイラー、S.(2020)、『グラント・ウッドの秘密』、デラウェア大学出版部、22ページ。

...少ない。。。

キー詳細

- この絵はウッドの妹、ナン・ウッド・グラハムを描いたもので、彼女は画家の最も有名な絵にも登場している、 アメリカン・ゴシック(1930).

- グラント・ウッドの研究者であるヘンリー・アダムス博士によれば、この作品は「グラント・ウッドの個人所有の最後の主要作品のひとつ」である。

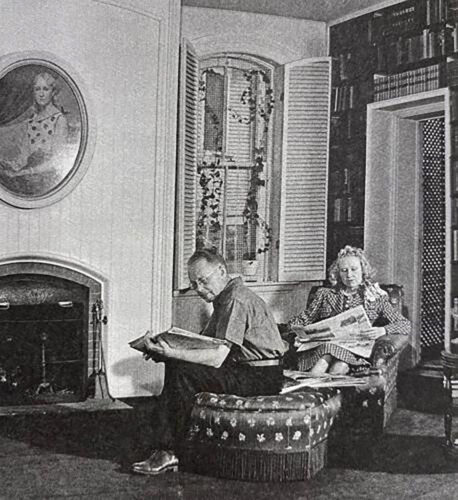

- ウッドはナンの肖像画を個人的に所蔵し、アイオワシティの自宅のリビングルームの目立つところに飾っていた。

- グラント・ウッドの絵画、特に肖像画は信じられないほど希少である。完成した油彩の肖像画がオークションに出品されたのは2点のみで、それに匹敵するような肖像画が公に落札されたことはない。

- そのわずか1年後に描かれた油彩の風景画『春耕』(1932年)は、2005年に6,960,000米ドルで落札された。ナンの肖像』の半分の大きさしかない。

- この肖像画は、2018年にホイットニー美術館で展示されるなど、幅広い展示歴がある: グラント・ウッドアメリカン・ゴシックとその他の寓話.

希少性

- 1930年に『アメリカン・ゴシック』を描いて以降、ウッドは毎年わずかな作品しか描かず、1942年にわずか50歳で早世したため、生涯に制作した円熟期の作品は30点あまりに過ぎなかった。

- グラント・ウッドの絵画、特に肖像画は信じられないほど希少である。完成した油彩の肖像画がオークションに出品されたのは2点のみで、それに匹敵するような肖像画が公に落札されたことはない。

- グラント・ウッドの研究者であるヘンリー・アダムス博士によれば、これは「グラント・ウッドの個人所有の最後の主要作品のひとつ」であるという。

- グラント・ウッドの作品について、アダムズ博士は「彼の作品はフェルメールと同じくらい珍しい」と述べている。

歴史

グラント・ウッドは、多くの学者、キュレーター、コレクターからアメリカン・リージョナリズムの父とみなされている。このスタイルは、田園風景や題材を特徴とし、ヨーロッパのモダニズムやパリのアヴァンギャルドが台頭していた時代に、具象美術に回帰したものである。この作品に描かれているのは、ウッドの妹ナンで、彼女はウッドのモデルとして、ウッドの最も有名な絵画を含むいくつかの作品に登場している、 アメリカン・ゴシックシカゴ美術館所蔵。

これほど複雑で重要なグラント・ウッドの作品は、販売されることはおろか、美術館のコレクション以外に登場することもほとんどない。この肖像画は、ウッドの作品の中でも最も重要な作品のひとつである。尊敬するグラント・ウッドの研究者であるヘンリー・アダムス博士は、「ナンの肖像」は「グラント・ウッドが個人で所有している最後の主要作品のひとつである」と述べている。

ナンの肖像アイオワ・シティの居間に飾られたこの絵を引き立てるために、家具や敷物を選んだほどだ。

ヘンリー・アダムス博士はこの絵を「彼の最も有名な絵のペンダント」と評している、 アメリカン・ゴシックのペンダント」と評している。さらにアダムズは、『ナンの肖像』は、『アメリカン・ゴシック』以後のナンのパブリックイメージを修正するためのものだったと推測している。 アメリカン・ゴシックその前年に描かれた『アメリカン・ゴシック』は有名になり、そうすることで2人の主題(ナンとその家族である歯科医)の間の(偽りの)婚外関係を仄めかすことになった。

ナンの肖像を制作した時期のエンドキャップにあたる。 植物を持つ女やアメリカン・ゴシックを制作した時期のエンドキャップである。1930年以降、画家は年に数点しか作品を描かず、どのような主題の油彩画でも完成品は本当に稀少なものとなった。

この肖像画のスタイルは、現代(当時)と19世紀アメリカの肖像画の融合である:「肖像画の重厚な縁取りのカーテン、荒涼とした背景、楕円形の形式(植民地時代やヴィクトリア時代に好まれた肖像画の形式)、フェデラル時代の椅子は、19世紀のアメリカの民衆絵画に見られる形式的要素の多くを想起させる。

この時期のグラント・ウッドの絵画は、1930年に最近ヨーロッパを訪れ、そこで見た北方ルネサンス美術の影響を受けて、若い頃のアカデミック/印象派のスタイルから移行し、中西部の主題を讃える成熟したスタイルを確立した。本作品は、2018年にニューヨークのホイットニー美術館で開催された展覧会を含め、幅広く展示されている: グラント・ウッドアメリカン・ゴシックとその他の寓話 .

オークショントップ

美術館所蔵の絵画

AUTHENTICATION

ナン・ウッド・グラハム 私の肖像画の物語 を1944年7月に書いた。この手紙の中で彼女は、ウッドが自分の肖像画を描いた思い入れのある理由、視覚的な装置としてひよことプラムが選ばれた経緯、そしてひよこを手に長い夜を過ごしたことをユーモアを交えて語っている。

画像ギャラリー

お 問い合わせ

お好きな方はこちらもどうぞ