格兰特-伍德(1891-1942)

种源

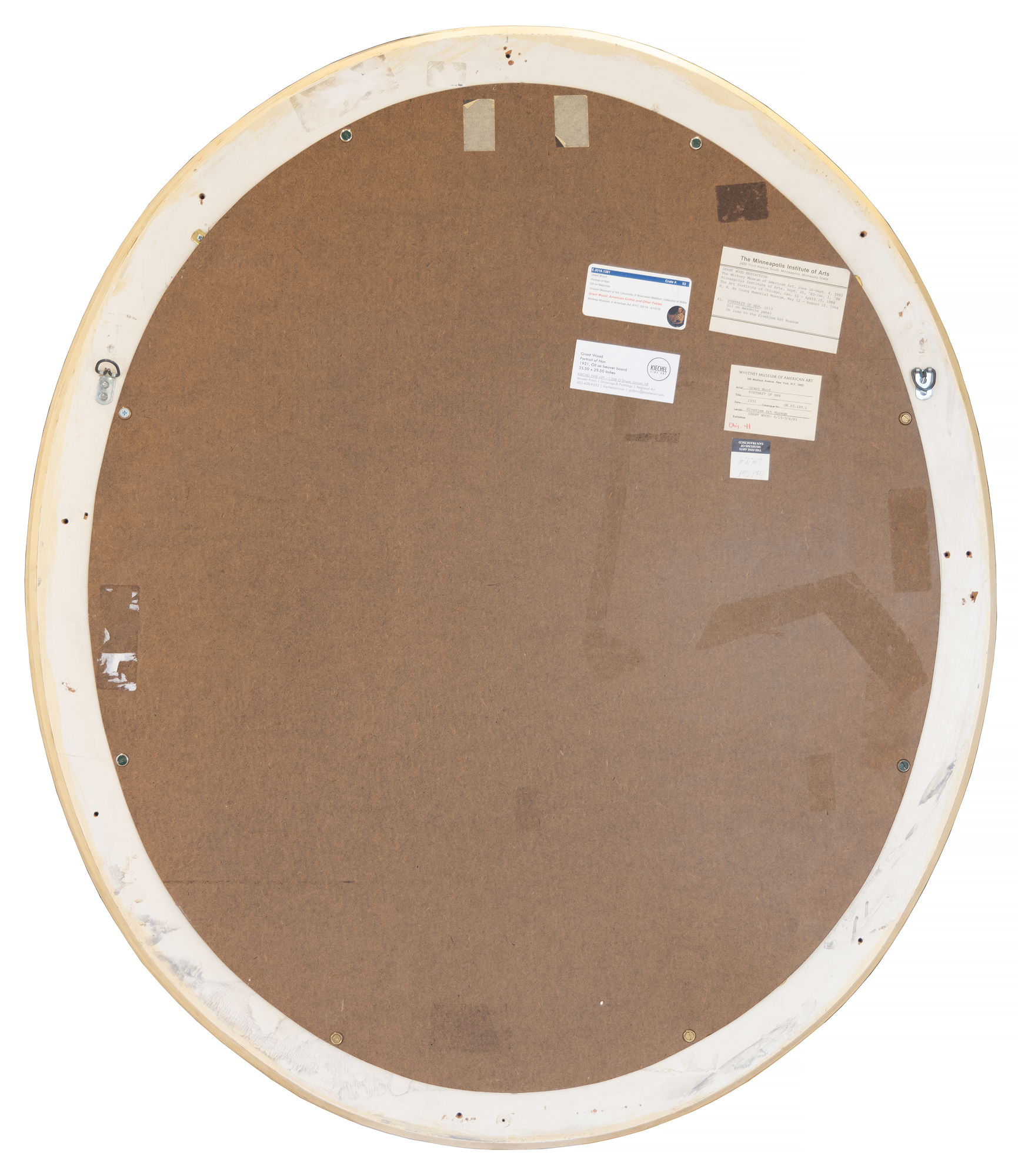

南-伍德-格雷厄姆,1942 年(格兰特-伍德的妹妹,后裔)大英百科全书》收藏馆,伊利诺伊州芝加哥,1945 年,从上述收藏馆购得

纽约杜文画廊,1952 年 12 月 11 日

威廉-本顿参议员,纽约和康涅狄格州南港,购自上图

海伦-博利,威斯康星州麦迪逊,1973 年(威廉-本顿参议员的女儿,后裔)

2020 年,现主人从上述人手中购得

展会信息

内布拉斯加州奥马哈,乔斯林纪念馆,开幕展,1931 年 11 月至 12 月伊利诺伊州,芝加哥...更。。。 增加罗宾逊画廊,格兰特-伍德画展,1933 年 6 月

纽约,费拉吉尔画廊,1934 年 6 月

芝加哥,伊利诺伊州,湖畔出版社画廊,格兰特-伍德素描和油画借展目录,1935 年 2 月至 3 月

纽约,费拉吉尔画廊,格兰特-伍德绘画作品展,1935 年 3 月至 4 月

爱荷华市,艺术节,爱荷华联合休息室,爱荷华大学,格兰特-伍德和马文-D-康恩画展,1939 年 7 月

芝加哥,伊利诺伊州,芝加哥艺术学院,格兰特-伍德绘画纪念展,第五十三届美国绘画和雕塑年展,1942 年 10 月至 12 月

伊利诺伊州芝加哥,芝加哥艺术学院,大英百科全书当代美国绘画作品收藏馆,1945 年 4 月 12 日至 5 月 13 日

世界博览会:康涅狄格州哈特福德,日本大阪,沃兹沃斯美术馆,本顿收藏:20 世纪美国绘画,1971 年 3 月至 1 月

威斯康星州麦迪逊,威斯康星大学麦迪逊分校 Chazen 美术馆,1981-2018 年(长期借展)

纽约惠特尼艺术博物馆、明尼苏达州明尼阿波利斯市、伊利诺伊州芝加哥市明尼阿波利斯艺术学院、加利福尼亚州旧金山芝加哥艺术学院、M.H. de Young 纪念博物馆、格兰特-伍德:地域主义视野,1983 - 1984 年

爱荷华州达文波特,格兰特-伍德百年庆典暨南-伍德纪念会,1991 年 2 月至 3 月

乔斯林艺术博物馆,内布拉斯加州奥马哈,爱荷华州达文波特,达文波特艺术博物馆,马萨诸塞州伍斯特,伍斯特艺术博物馆,格兰特-伍德:1995 年 12 月至 1996 年 12 月,美国艺术大师展

哥伦布艺术博物馆,俄亥俄州哥伦布市,维也纳现代艺术博物馆/路德维希基金会,奥地利维也纳市,路德维希当代艺术博物馆,匈牙利布达佩斯市,麦迪逊艺术中心,威斯康星州麦迪逊市,南达科他州苏福尔斯市,华盛顿艺术与科学展馆,伊甸园的幻觉:美国中心地带的愿景,2000 年 2 月 - 2001 年 8 月

爱荷华州锡达拉皮兹,锡达拉皮兹艺术博物馆,特纳巷 5 号的格兰特-伍德,2006 年 9 月至 1 月

华盛顿特区,伦威克画廊,史密森美国艺术博物馆,格兰特-伍德工作室:美国哥特式风格的发源地,2006 年 3 月至 7 月

纽约惠特尼美国艺术博物馆,格兰特-伍德:美国哥特式和其他寓言,2018年3月至6月

佛罗里达州西棕榈滩,安-诺顿雕塑公园,发现创造力:美国艺术大师,2024 年 1 月 10 日至 3 月 17 日

文学

Corn, W. M. (1985),《格兰特-伍德:地区主义者的视野》,耶鲁大学出版社,第 102 页。Graham, N. W., Zug, J., & McDonald, J. (1993), My Brother, Grant Wood, State Historical Society of Iowa, p. 46, 106, 111-112, back cover

Dennis, J.M. (1998), Renegade Regionalists:格兰特-伍德、托马斯-哈特-本顿和约翰-斯图尔特-库里的现代独立》,威斯康星大学出版社,第 106 和 108 页。

Milosch, J.C. (2005),《格兰特-伍德的工作室》:美国哥特式的发源地》,锡达拉皮兹艺术博物馆,第 19 页

Maroney, J. (2010), Fresh Perspectives on Grant Wood, Charles Sheeler, and George H. Durrie, Gala Books, p. 32, 76-77

Evans, T. (2010), Grant Wood:A Life》,企鹅兰登书屋,第 120-27 页,第 302 页。

泰勒,S.(2020 年),《格兰特-伍德的秘密》,特拉华大学出版社,第 22 页

...少。。。

关键细节

- 这幅画描绘的是伍德的妹妹南-伍德-格雷厄姆(Nan Wood Graham),她也出现在画家最著名的画作中、 美国哥特式(1930).

- 根据格兰特-伍德学者亨利-亚当斯博士的说法,这是 "私人手中格兰特-伍德最后的主要作品之一"。

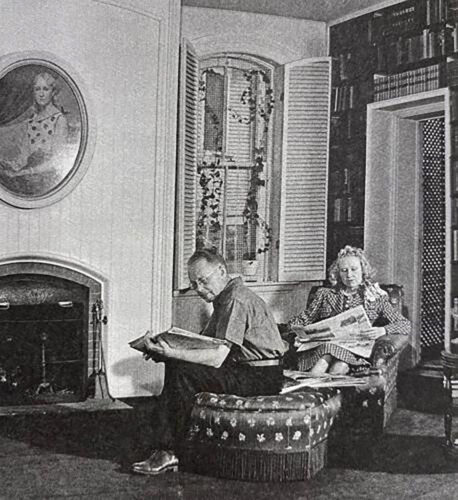

- 伍德将南的肖像作为个人收藏,并将其放在爱荷华市家中客厅的显眼位置。

- 格兰特-伍德的画作--尤其是他的肖像画--非常罕见。只有两幅完成的油画肖像在拍卖会上出现过,而真正具有可比性的肖像画从未公开出售过。

- 仅一年后创作的油画风景《春耕》(1932 年)于 2005 年以 696 万美元的价格售出。这幅作品的尺寸只有《楠的肖像》的一半。

- 这幅肖像画拥有广泛的展览历史,包括 2018 年在惠特尼美国艺术博物馆举办的展览: 格兰特-伍德:美国哥特式和其他寓言.

稀有性

- 在 1930 年创作了《美国哥特式》之后,伍德每年只创作少量作品,由于 1942 年年仅 50 岁就英年早逝,他一生只创作了 30 多幅成熟的画作。

- 格兰特-伍德的画作--尤其是他的肖像画--非常罕见。只有两幅完成的油画肖像在拍卖会上出现过,而真正具有可比性的肖像画从未公开出售过。

- 根据格兰特-伍德学者亨利-亚当斯博士的说法,这是 "私人手中格兰特-伍德最后的主要作品之一"。

- 关于格兰特-伍德的作品,亚当斯博士曾说:"他的作品几乎和维米尔的作品一样罕见"。

历史

格兰特-伍德被许多学者、策展人和收藏家视为美国地域主义之父。在欧洲现代主义和巴黎前卫艺术大行其道之时,这种风格以乡村场景和主题为特色,并回归到具象艺术。这幅作品中的人物是伍德的妹妹南,她曾是伍德的模特,出现在多幅作品中,包括伍德最著名的画作、 美国哥特式芝加哥艺术学院收藏。

格兰特-伍德如此复杂和重要的作品很少出现在博物馆收藏之外,更不用说出售了。这幅肖像画是伍德最重要的作品之一。受人尊敬的格兰特-伍德学者亨利-亚当斯博士说,《南的肖像》是 "私人手中格兰特-伍德最后的重要作品之一"。

南的肖像这幅画一直由艺术家收藏,直到他去世,也是他唯一保留的一幅画--也是他家中唯一的一幅画,他甚至为这幅挂在爱荷华市客厅里的画挑选了家具和地毯。

亨利-亚当斯博士将这幅画描述为 "他最著名画作的挂件"、 美国哥特式的挂件"。亚当斯进一步推测,《南的肖像》意在纠正南在《美国哥特式》之后的公众形象。 美国哥特式的公众形象,因为前一年创作的《美国哥特式》已经声名鹊起,而《南的肖像》则影射了两个主题人物(南和他们家的牙医)之间(虚假的)婚外关系。

南的肖像是艺术家早期创作的最后一幅肖像画,也是他创作《带植物的女人》时期的尾声。 植物女人和 "美国哥特式"的最后一幅作品。1930 年之后,艺术家每年只创作几幅作品,因此任何主题的油画成品都非常罕见。

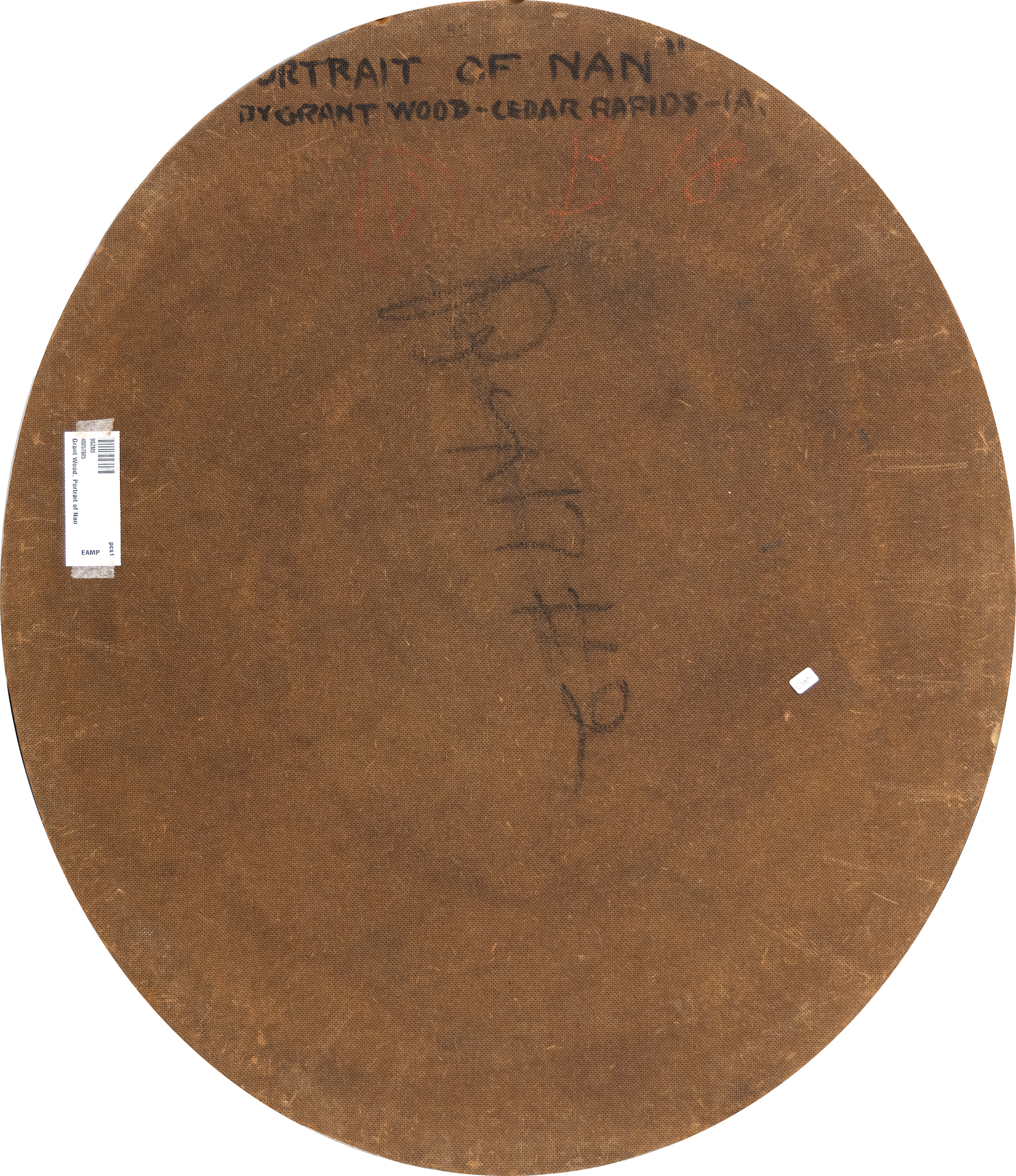

这幅肖像画的造型融合了当代(当时)和 19 世纪美国肖像画的风格:"肖像的厚重框幕、鲜明的背景、椭圆形的格式(殖民地和维多利亚时代所喜爱的肖像格式)以及联邦时代的椅子,让人联想到 19 世纪美国民间绘画中的许多形式元素"。

格兰特-伍德这一时期的画作受到了他最近一次欧洲之行的影响,1930 年,他在欧洲看到了北方文艺复兴时期的艺术,当时他从年轻时的学院派/印象派风格中走了出来,形成了自己以中西部题材为主题的成熟风格。这幅画已广泛展出,包括 2018 年在纽约惠特尼美国艺术博物馆举办的展览: 格兰特-伍德:美国哥特式和其他寓言 .

最佳拍卖结果

博物馆藏画

认证

南-伍德-格雷厄姆撰写了 我肖像的故事 1944年7月。在这封信中,她深入阐述了伍德为她画肖像的深思熟虑的原因,以及如何选择小鸡和梅花作为视觉元素,并幽默地讲述了手捧小鸡的漫漫长夜。

图片库

询问

你可能也喜欢