RUFINO TAMAYO (1899-1991)

Procedencia

Colección de Edward Chodorov, Beverly Hills, CaliforniaColección de Miss Fanny Brice, Los Ángeles, California

Mary-Anne Martin | Fine Art, Nueva York

Colección privada

Colección privada, por descendencia

Exposición

Nagoya, Japón, Museo de Arte de la Ciudad de Nagoya, "Retrospectiva de Rufino Tamayo", octubre - 12 de diciembre de 1993.Ciudad de México, México, Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, "Rufino Tamayo del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 -1950," 19 de octubre - 25 de febrero de 1996

Santa Bárbara, California, San...Más....Museo de Arte de Ta Bárbara, "Tamayo: un icono moderno reinterpretado", del 17 de febrero al 27 de mayo de 2007.

Literatura

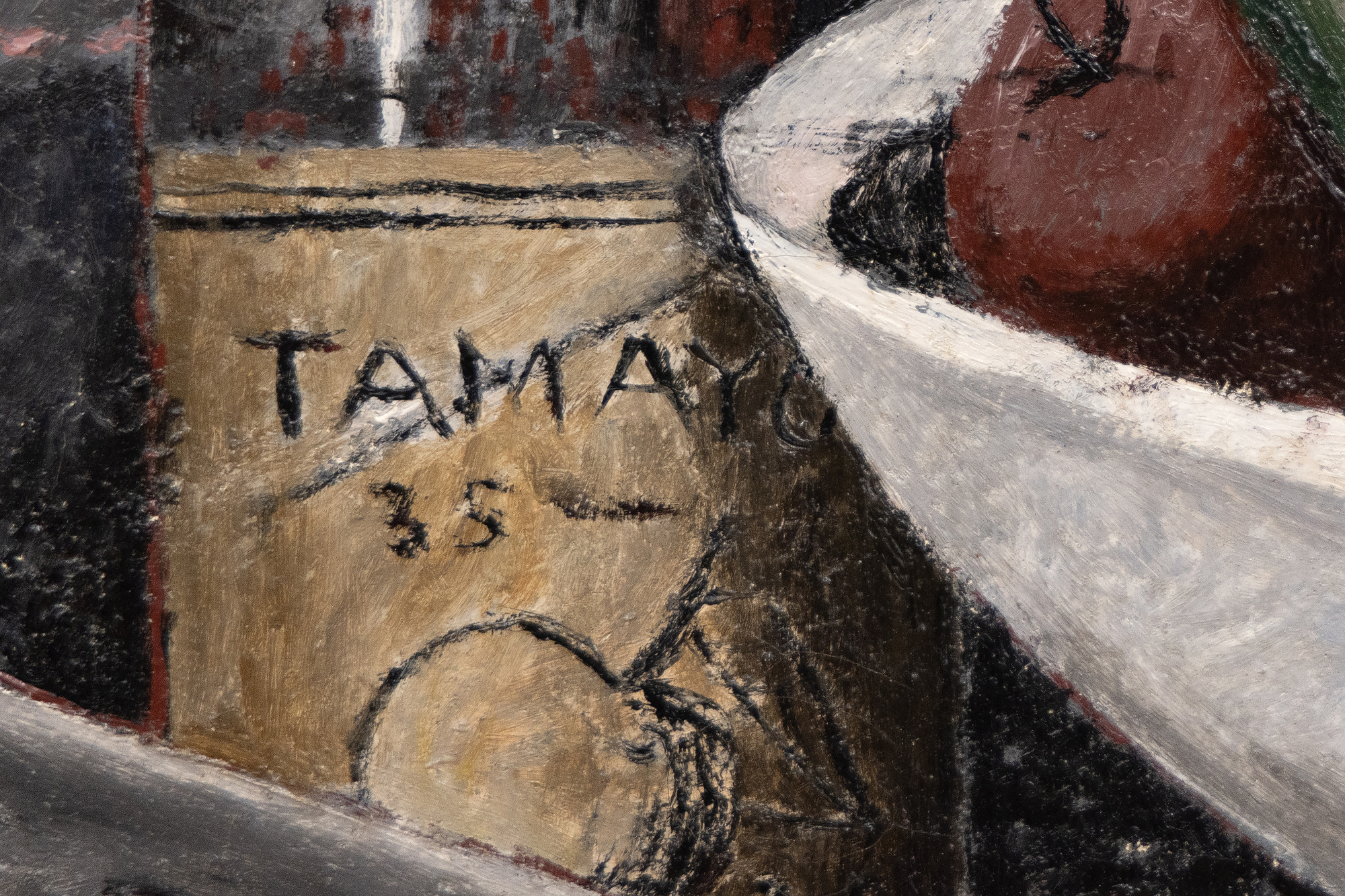

"Hoy se inaugura la exposición de Rufino Tamayo en el Pasaje América", El Universal, noviembre de 1935 (ilustrado).Robert Goldwater, Rufino Tamayo, Nueva York, NY, 1947, p. XVI (ilustrado p. 56)

Justino Fernández, Rufino Tamayo, Ciudad de México, México, 1948

Ceferino Palencia, Rufino Tayamo, Ciudad de México, México, 1950, no. 4 (ilustrado)

Museo de Arte de la Ciudad de Nagoya, Retrospectiva de Rufino Tamayo, Nagoya, Japón, 1993, nº 17, p. 34 (ilustrado en color)

Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, Rufino Tamayo: del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 - 1950, Ciudad de México, México, 1995, no. 56, p. 46 (ilustrado en color)

Octavio Paz, Transfiguraciones en Historia del Arte de Oaxaca, Ciudad de México, México, 1998, no. 5, p. 16-17 (ilustrado en color)

Octavio Paz, Rufino Tamayo, Ciudad de México, México, 2003, no. 5 (ilustrado en color)

Diana C. DuPont, Juan Carlos Pereda, et. al., Tamayo; A Modern Icon Reinterpreted, Santa Barbara, CA, 2007, pl. 43, p. 162 (ilustrado en color)

...MENOS.... Precio1,850,000

Historia

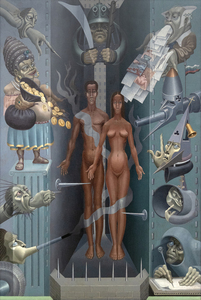

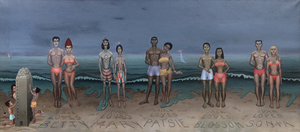

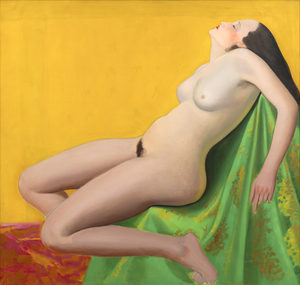

A mediados de la década de 1920, Rufino Tamayo se embarcó en la fase crucial de su desarrollo como colorista sofisticado y contemporáneo. En Nueva York conoció la obra innovadora de Picasso, Braque y Giorgio de Chirico, así como el impacto perdurable del cubismo. Explorando los valores pictóricos y plásticos a través de temas procedentes de escenas callejeras, la cultura popular y el tejido de la vida cotidiana, comenzó a tomar forma su enfoque único del color y la forma. Fue un cambio fundamental hacia una estética cosmopolita, que le apartó del fervor nacionalista defendido por las narrativas políticamente cargadas del movimiento muralista mexicano. Al centrarse en la vitalidad de la cultura popular, captó la identidad mexicana esencial que priorizaba los valores artísticos universales sobre el comentario social y político explícito. Este enfoque subrayó su compromiso con la redefinición del arte mexicano en la escena mundial y puso de relieve sus innovadoras aportaciones al diálogo modernista.

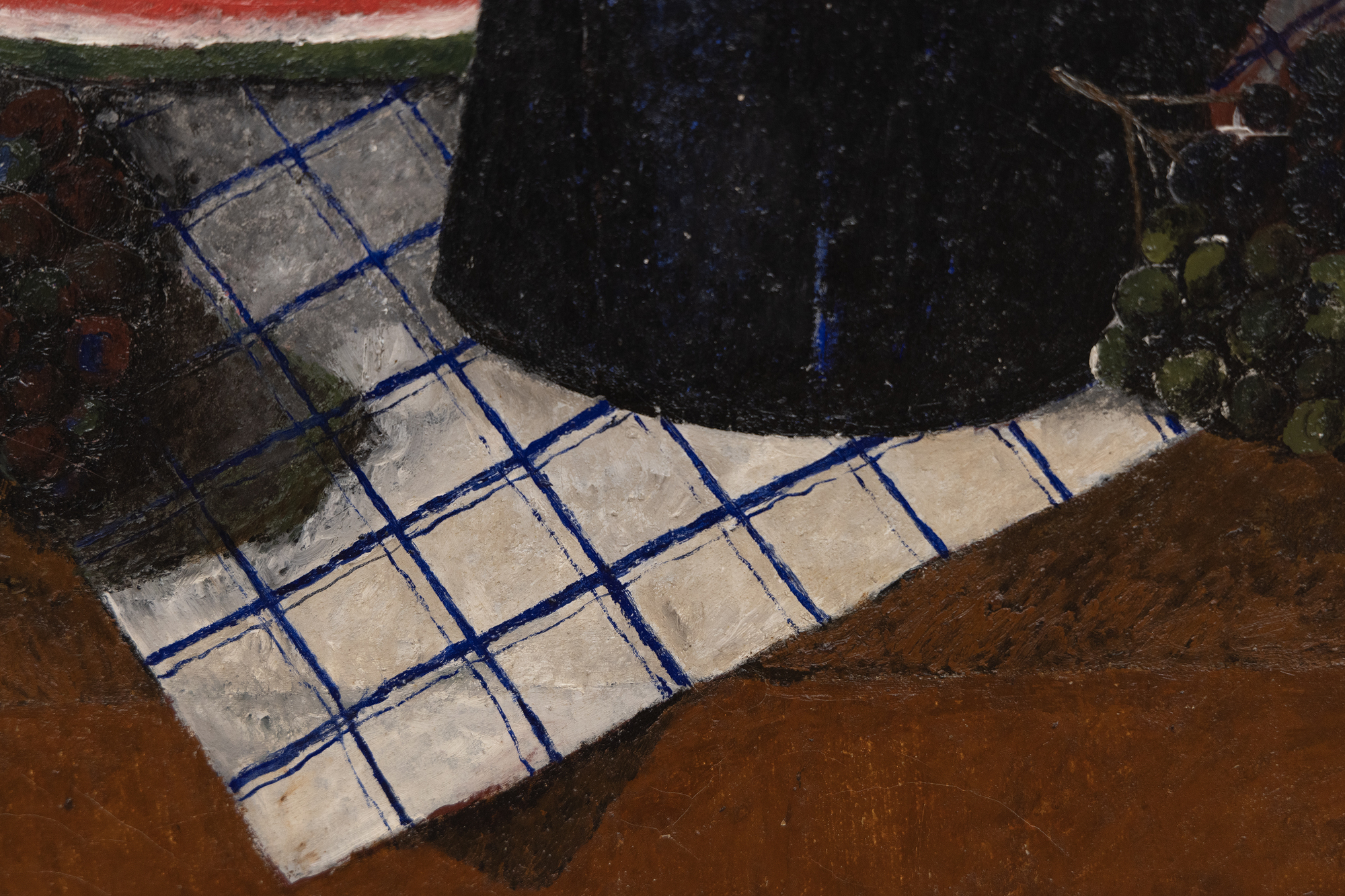

Al igual que Cézanne, Tamayo elevó el género de la naturaleza muerta a algunas de sus expresiones más hermosamente sencillas. Sin embargo, la gran sofisticación subyace en la facilidad con la que Tamayo fusiona los vibrantes motivos mexicanos con las influencias vanguardistas de la Escuela de París. Como revela Naturaleza Muerta, de 1935, Tamayo se negó a caer en la mera decoración que a menudo caracteriza al arte contemporáneo de la Escuela de París, con la que su obra se compara. En cambio, la disposición de sandías, botellas, una cafetera y otros objetos en una tonalidad aleccionadora y terrenal, y un espacio indeterminado y poco profundo, recuerdan el temprano interés de Tamayo por el surrealismo. Una matriz cuadrada superpuesta subraya el contraste entre los temas orgánicos de la pintura y la estructura abstracta e intelectualizada que se les impone, profundizando la interpretación de la exploración del artista de la percepción visual y la representación. De este modo, la cuadrícula sirve para navegar entre el mundo visible y las estructuras subyacentes que informan nuestra comprensión del mismo, invitando al espectador a considerar la interacción entre realidad y abstracción, sensación y análisis.

DATOS IMPORTANTES

- Al centrarse en la vitalidad de la cultura popular, Rufino Tamayo captó la identidad mexicana esencial que priorizaba los valores artísticos universales sobre el comentario social y político explícito. Este enfoque subrayó su compromiso con la redefinición del arte mexicano en la escena mundial y puso de relieve sus innovadoras aportaciones al diálogo modernista.

- Al igual que Cézanne, Tamayo elevó el género de la naturaleza muerta a algunas de sus expresiones más hermosamente sencillas. Sin embargo, la gran sofisticación subyace en la facilidad con la que Tamayo fusiona los vibrantes motivos mexicanos con las influencias vanguardistas de la Escuela de París.

- Como revela Naturaleza Muerta, de 1935, Tamayo se negó a caer en la mera decoración que a menudo caracteriza a la escuela contemporánea del arte parisino con la que su obra se compara. En cambio, la disposición de sandías, botellas, una cafetera y otros objetos en una tonalidad aleccionadora y terrenal y en un espacio indeterminado y poco profundo recuerda el temprano interés de Tamayo por el surrealismo.

CONOCIMIENTOS DEL MERCADO

- Este cuadro se ha publicado en 9 libros y se ha expuesto en 3 museos.

- 10 obras de Tamayo han superado la barrera de los 3 millones de dólares en subasta (ver abajo) y 2 de ellas eran de sandías.

- Según Art Market Research, con sede en Londres, los precios de mercado de Tamayo han experimentado una tasa compuesta de crecimiento anual de 7.5% desde 1976 (ver gráfica de AMR).

- Diez cuadros de Tamayo han superado los 3 millones de dólares en subasta.

- Varias de las ventas más importantes han sido de cuadros con rodajas de sandía.

Los mejores resultados en las subastas

Pinturas comparables vendidas en subastas

Pinturas en colecciones de museos

Recursos adicionales

RUFINO TAMAYO POR GREGORIO LUKE

RUFINO TAMAYO - LAS FUENTES DE SU ARTE

MATERIALES Y MEMORIAS: MIXOGRAFIA Y TAMAYO

Galería de imágenes

Preguntar

También le puede gustar

,_new_mexico_tn40147.jpg )