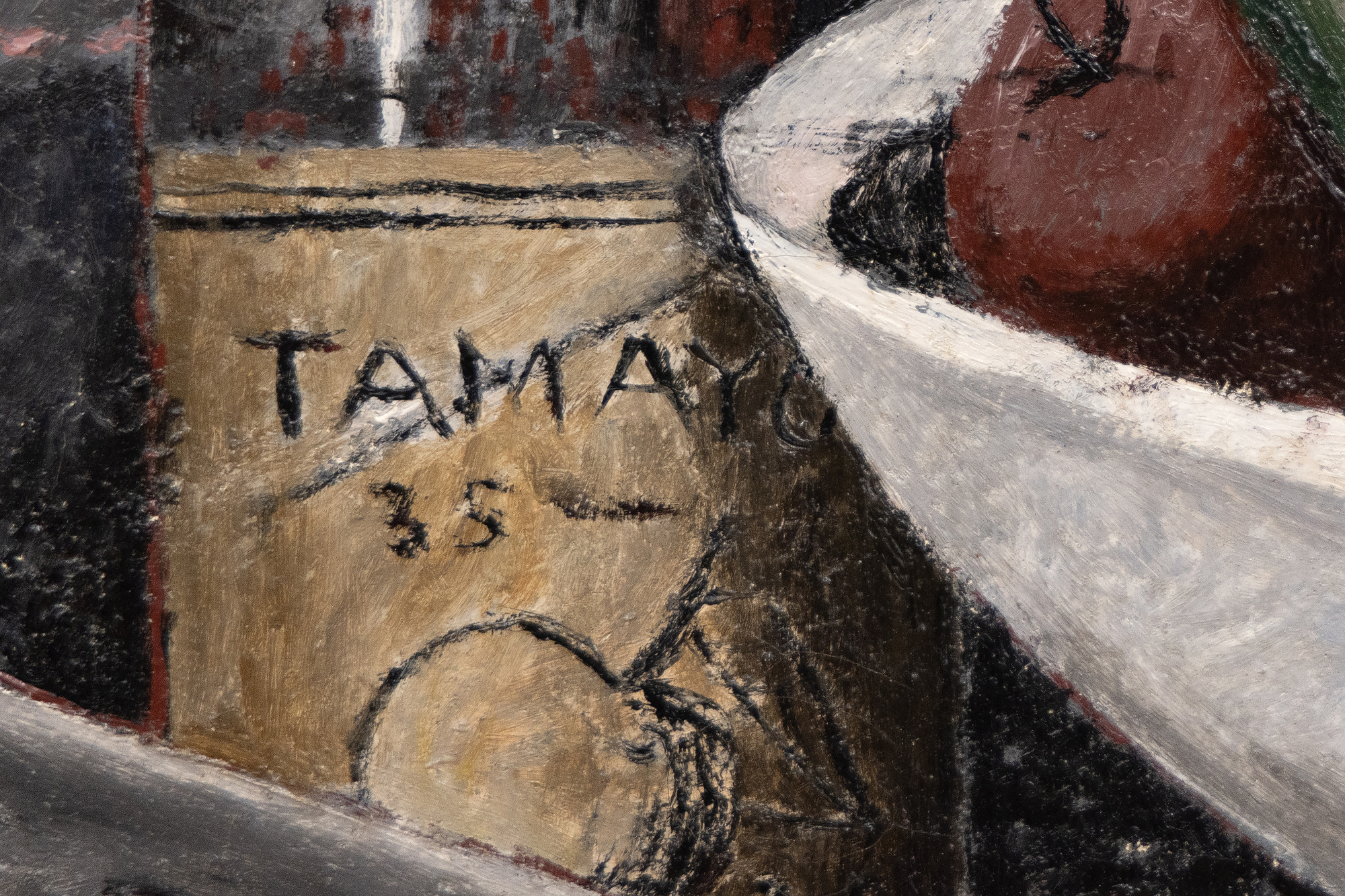

רופינו טמאיו(1899-1991)

מקור ומקור

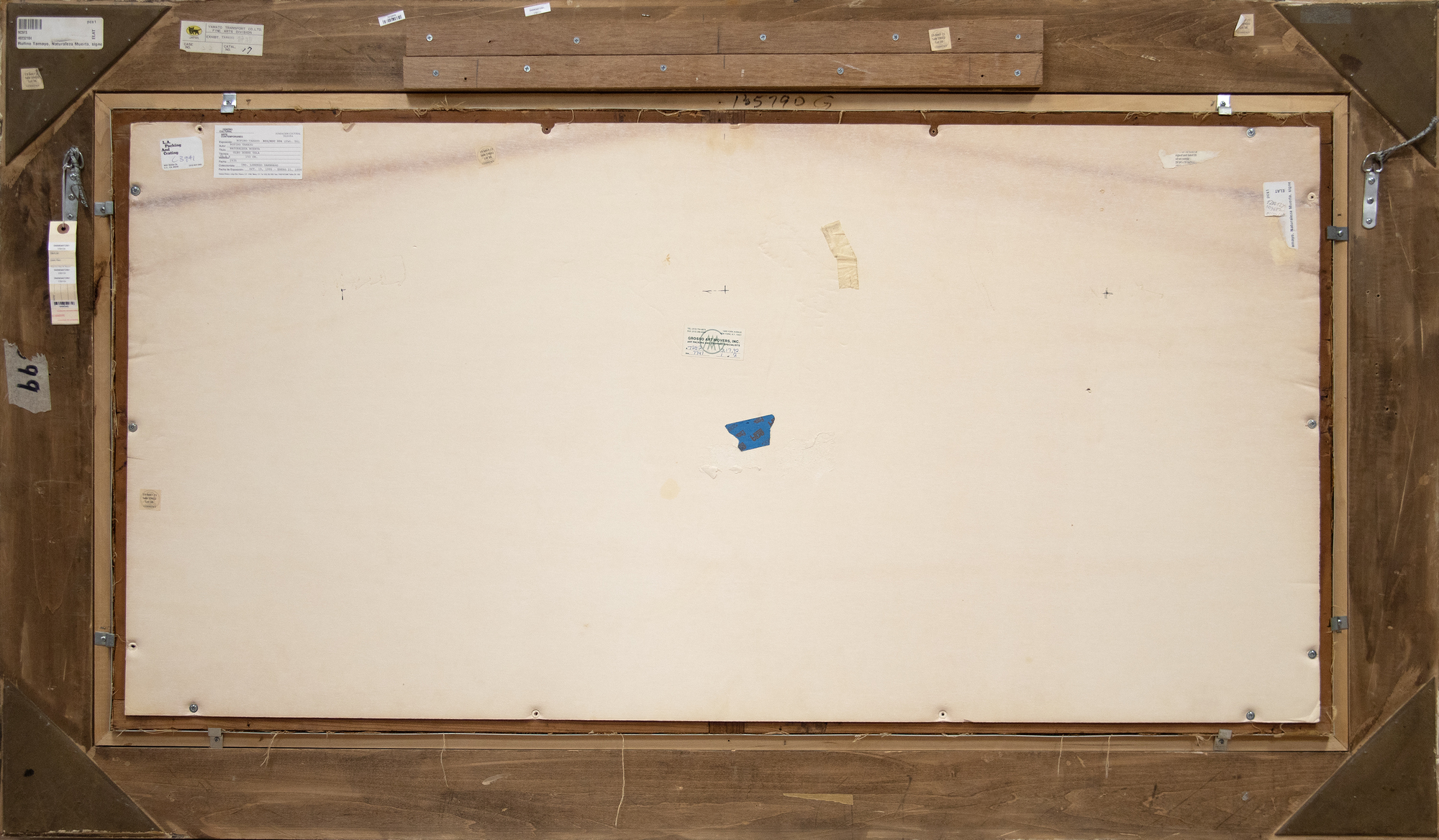

האוסף של אדוארד צ'ודורוב, בוורלי הילס, קליפורניההאוסף של מיס פאני בריס, לוס אנג'לס, קליפורניה

מרי-אן מרטין | אמנות יפה, ניו יורק

אוסף פרטי

אוסף פרטי, לפי מוצא

תערוכה

נגויה, יפן, מוזיאון העיר נאגויה לאמנות, "Rupino Tamayo Retrospective", אוקטובר - 12 בדצמבר, 1993מקסיקו סיטי, מקסיקו, Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, "Rufino Tamayo del Reflejo al Sueno 1920 -1950", 19 באוקטובר - 25 בפברואר 1996

סנטה ברברה, קליפורניה, סן... עוד...מוזיאון ברברה לאמנות, "טמאיו: אייקון מודרני שפורש מחדש", 17 בפברואר - 27 במאי 2007

ספרות

"Hoy se inaugura la exposición de Rufino Tamayo en el Pasaje América", אל יוניברסל, נובמבר 1935 (מאויר)רוברט גולדווטר, רופינו טמאיו, ניו יורק, ניו יורק, 1947, עמ' XVI (מאויר עמ' 56)

Justino Fernández, Rufino Tamayo, מקסיקו סיטי, מקסיקו, 1948

Ceferino Palencia, Rufino Tayamo, מקסיקו סיטי, מקסיקו, 1950, מס' 4 (מאויר)

מוזיאון העיר נגויה, רטרוספקטיבה של רופינו טמאיו, נגויה, יפן, 1993, מס' 17, עמ' 34 (מאויר בצבע)

Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, Rufino Tamayo: del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 – 1950, מקסיקו סיטי, מקסיקו, 1995, מס' 56, עמ' 46 (מאויר בצבע)

אוקטביו פז, Transfiguraciones en Historia del Arte de Oaxaca, מקסיקו סיטי, מקסיקו, 1998, מס' 5, עמ' 16-17 (מאויר בצבע)

אוקטביו פז, רופינו טמאיו, מקסיקו סיטי, מקסיקו, 2003, מס' 5 (מאויר בצבע)

דיאנה סי דופונט, חואן קרלוס פרדה, et. אל., טמאיו; A Modern Icon Reinterpreted, Santa Barbara, CA, 2007, pl. 43, p. 162 (מאויר בצבע)

... פחות... מחיר 1,850,000

היסטוריה

באמצע שנות העשרים החל רופינו טמאיו בשלב הפיתוח המכריע כקולוריסט מתוחכם ועכשווי. בניו יורק הוא נתקל ביצירותיהם פורצות הדרך של פיקאסו, בראק וג'ורג'יו דה קיריקו, יחד עם ההשפעה המתמשכת של הקוביזם. הוא חקר ערכים ציוריים ופלסטיים דרך נושאים שמקורם בסצנות רחוב, תרבות פופולרית ומרקם חיי היומיום, וגישתו הייחודית לצבע ולצורה החלה לקרום עור וגידים. היה זה שינוי מכריע לעבר אסתטיקה קוסמופוליטית, שהבדיל אותו מהלהט הלאומני שבו דגלו הנרטיבים הטעונים פוליטית של התנועה המורליסטית המקסיקנית. על ידי התמקדות בחיוניותה של התרבות הפופולרית, הוא לכד את הזהות המקסיקנית המהותית שהעדיפה ערכים אמנותיים אוניברסליים על פני פרשנות חברתית ופוליטית מפורשת. הגישה הדגישה את מחויבותו להגדרה מחדש של האמנות המקסיקנית על הבמה העולמית והדגישה את תרומתו החדשנית לדיאלוג המודרניסטי.

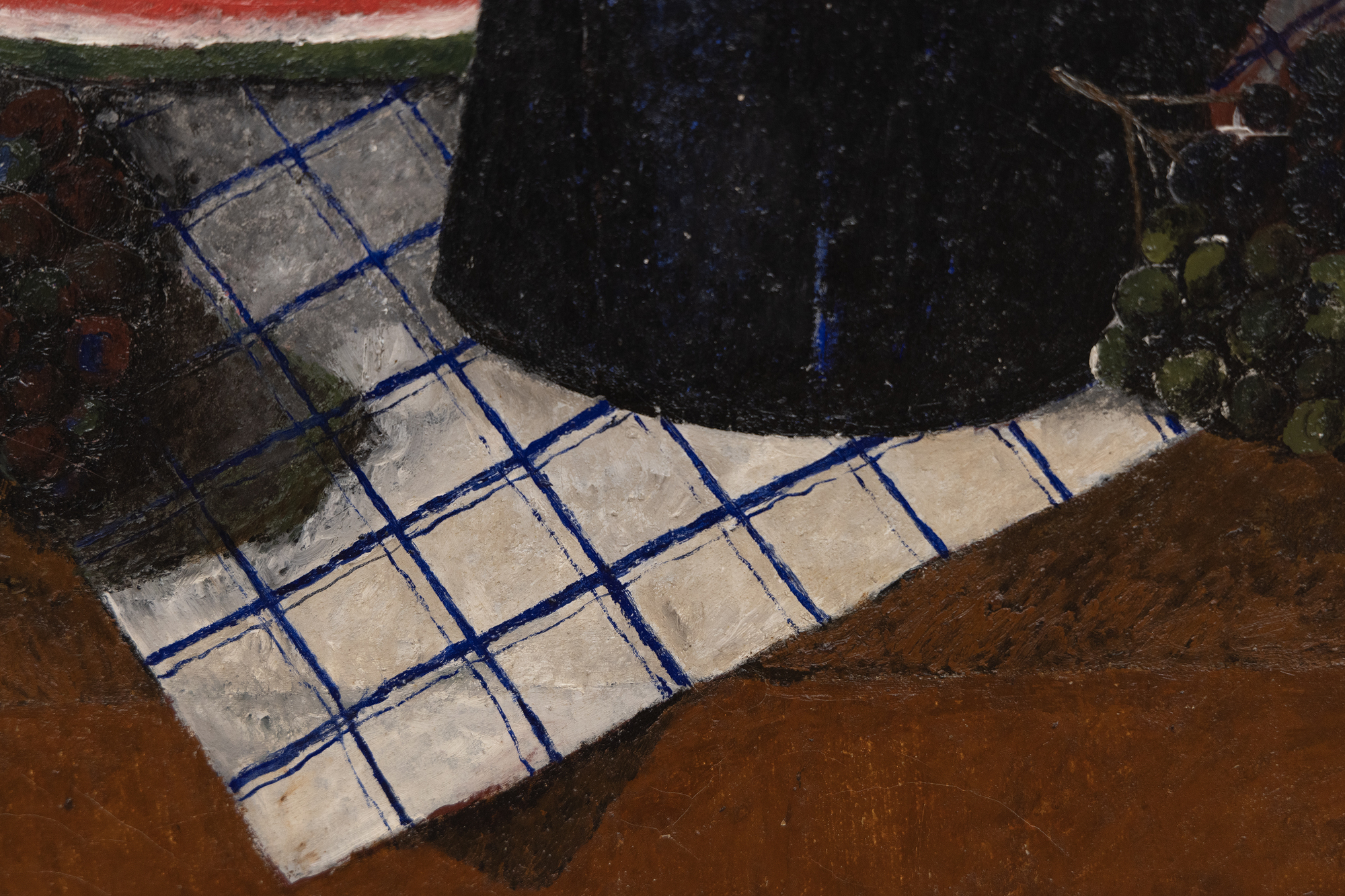

כמו סזאן, טמאיו העלה את ז'אנר הטבע הדומם לכמה מהביטויים הפשוטים והיפים ביותר שלו. עם זאת, התחכום הגבוה עומד בבסיס הקלות שבה טמאיו משלב מוטיבים מקסיקניים תוססים עם ההשפעות האוונגרדיות של אסכולת פריז. כפי שמגלה נטורלזה מוארטה מ-1935, טמאיו סירב לשקוע בעיטור גרידא שמאפיין לעתים קרובות את האמנות העכשווית של אסכולת פריז שעמה עבודתו עורכת השוואות. במקום זאת, הסידור שלו של אבטיחים, בקבוקים, קנקן קפה ופריטים שונים המבוימים בתוך טונאליות מפוכחת וארצית וחלל רדוד וחסר החלטיות מזכיר את העניין המוקדם של טמאיו בסוריאליזם. מטריצה מרובעת מכוסה מדגישה את הניגוד בין הסובייקטים האורגניים של הציור לבין המבנה המופשט והאינטלקטואלי שנכפה עליהם, ומעמיקה את הפרשנות של חקירת האמן את התפיסה והייצוג החזותיים. בדרך זו, הרשת משמשת לנווט בין העולם הנראה לעין לבין המבנים הבסיסיים המשפיעים על הבנתנו אותו, ומזמינה את הצופים לשקול את יחסי הגומלין בין מציאות להפשטה, תחושה וניתוח.

עובדות חשובות

- על ידי התמקדות בחיוניותה של התרבות הפופולרית, רופינו טמאיו לכד את הזהות המקסיקנית המהותית שהעדיפה ערכים אמנותיים אוניברסליים על פני פרשנות חברתית ופוליטית מפורשת. הגישה הדגישה את מחויבותו להגדרה מחדש של האמנות המקסיקנית על הבמה העולמית והדגישה את תרומתו החדשנית לדיאלוג המודרניסטי.

- כמו סזאן, טמאיו העלה את ז'אנר הטבע הדומם לכמה מהביטויים הפשוטים והיפים ביותר שלו. עם זאת, התחכום הגבוה עומד בבסיס הקלות שבה טמאיו משלב מוטיבים מקסיקניים תוססים עם ההשפעות האוונגרדיות של אסכולת פריז.

- כפי שמגלה נטורלזה מוארטה מ-1935, טמאיו סירב לשקוע בעיטור גרידא שמאפיין לעתים קרובות את האמנות העכשווית של אסכולת פריז שעמה עבודתו עורכת השוואות. במקום זאת, הסידור שלו של אבטיחים, בקבוקים, קנקן קפה ופריטים שונים המבוימים בתוך טונאליות מפוכחת וארצית וחלל רדוד וחסר החלטיות מזכיר את העניין המוקדם של טמאיו בסוריאליזם.

תובנות שוק

- ציור זה פורסם ב-9 ספרים והוצג ב-3 מוזיאונים.

- 10 יצירות אמנות של טמאיו עברו את רף 3 מיליון הדולר במכירה פומבית (ראו להלן) ו-2 מהן היו לנושאי אבטיח ("סנדיאס").

- על פי Art Market Research שבסיסה בלונדון, מחירי השוק של טמאיו חוו שיעור צמיחה שנתי מורכב של 7.5% מאז 1976 (ראו גרף AMR).

- עשרה ציורים של טמאיו גרפו יותר מ-3 מיליון דולר במכירה פומבית.

- מכירות מובילות מרובות היו עבור ציורים הכוללים אבטיח פרוס.