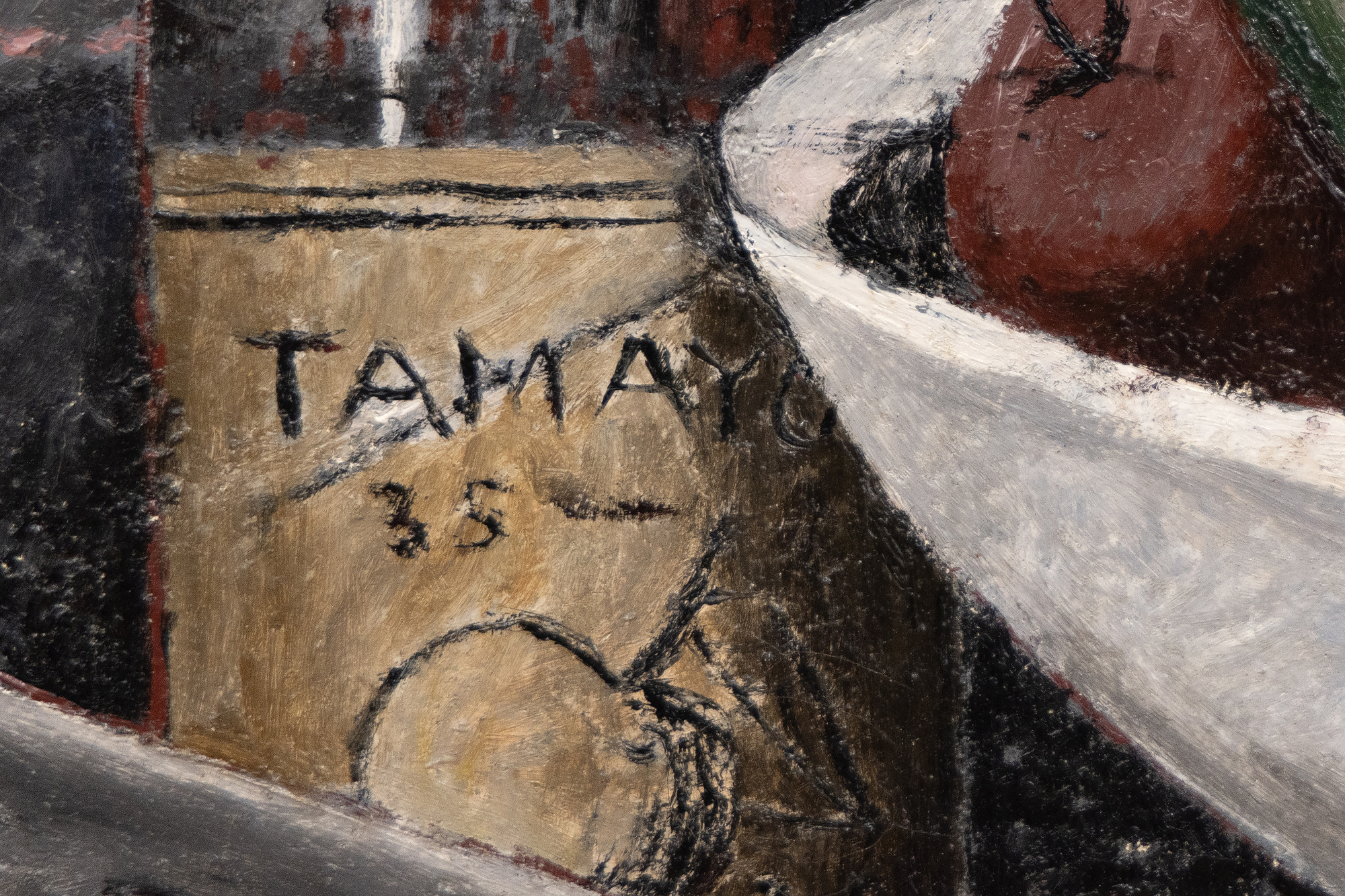

RUFINO TAMAYO (1899-1991)

Provenienz

Die Sammlung von Edward Chodorov, Beverly Hills, KalifornienDie Sammlung von Miss Fanny Brice, Los Angeles, Kalifornien

Mary-Anne Martin | Bildende Kunst, New York

Privatsammlung

Privatsammlung, durch Abstammung

Ausstellung

Nagoya, Japan, Nagoya City Art Museum, "Rufino Tamayo Retrospektive", Oktober - 12. Dezember 1993Mexiko-Stadt, Mexiko, Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, "Rufino Tamayo del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 -1950", 19. Oktober - 25. Februar 1996

Santa Barbara, Kalifornien, San...Mehr.....Ta Barbara Museum of Art, "Tamayo: Eine moderne Ikone neu interpretiert", 17. Februar - 27. Mai 2007

Literaturhinweise

"Hoy se inaugura la exposición de Rufino Tamayo en el Pasaje América", El Universal, November 1935 (illustriert)Robert Goldwater, Rufino Tamayo, New York City, NY, 1947, S. XVI (illustriert S. 56)

Justino Fernández, Rufino Tamayo, Mexiko-Stadt, Mexiko, 1948

Ceferino Palencia, Rufino Tayamo, Mexiko-Stadt, Mexiko, 1950, Nr. 4 (illustriert)

Nagoya City Art Museum, Rufino Tamayo Retrospektive, Nagoya, Japan, 1993, Nr. 17, S. 34 (in Farbe)

Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, Rufino Tamayo: del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 - 1950, Mexiko-Stadt, Mexiko, 1995, Nr. 56, S. 46 (in Farbe abgebildet)

Octavio Paz, Transfiguraciones en Historia del Arte de Oaxaca, Mexiko-Stadt, Mexiko, 1998, Nr. 5, S. 16-17 (in Farbe illustriert)

Octavio Paz, Rufino Tamayo, Mexiko-Stadt, Mexiko, 2003, Nr. 5 (in Farbe illustriert)

Diana C. DuPont, Juan Carlos Pereda, et. al., Tamayo; A Modern Icon Reinterpreted, Santa Barbara, CA, 2007, Taf. 43, S. 162 (in Farbe)

...WENIGER..... Preis1,850,000

Geschichte

Mitte der 1920er Jahre begann für Rufino Tamayo die entscheidende Entwicklungsphase zu einem anspruchsvollen, zeitgenössischen Koloristen. In New York begegnete er den bahnbrechenden Werken von Picasso, Braque und Giorgio de Chirico sowie dem anhaltenden Einfluss des Kubismus. Indem er malerische und plastische Werte anhand von Motiven aus Straßenszenen, der Populärkultur und dem täglichen Leben erforschte, nahm sein einzigartiger Ansatz für Farbe und Form Gestalt an. Es war ein entscheidender Wandel hin zu einer kosmopolitischen Ästhetik, der ihn von der nationalistischen Inbrunst der politisch aufgeladenen Erzählungen der mexikanischen Wandmalerbewegung abhob. Indem er sich auf die Vitalität der Populärkultur konzentrierte, erfasste er die wesentliche mexikanische Identität, die universellen künstlerischen Werten Vorrang vor expliziten sozialen und politischen Kommentaren einräumte. Dieser Ansatz unterstrich sein Engagement für die Neudefinition der mexikanischen Kunst auf der Weltbühne und hob seine innovativen Beiträge zum Dialog mit der Moderne hervor.

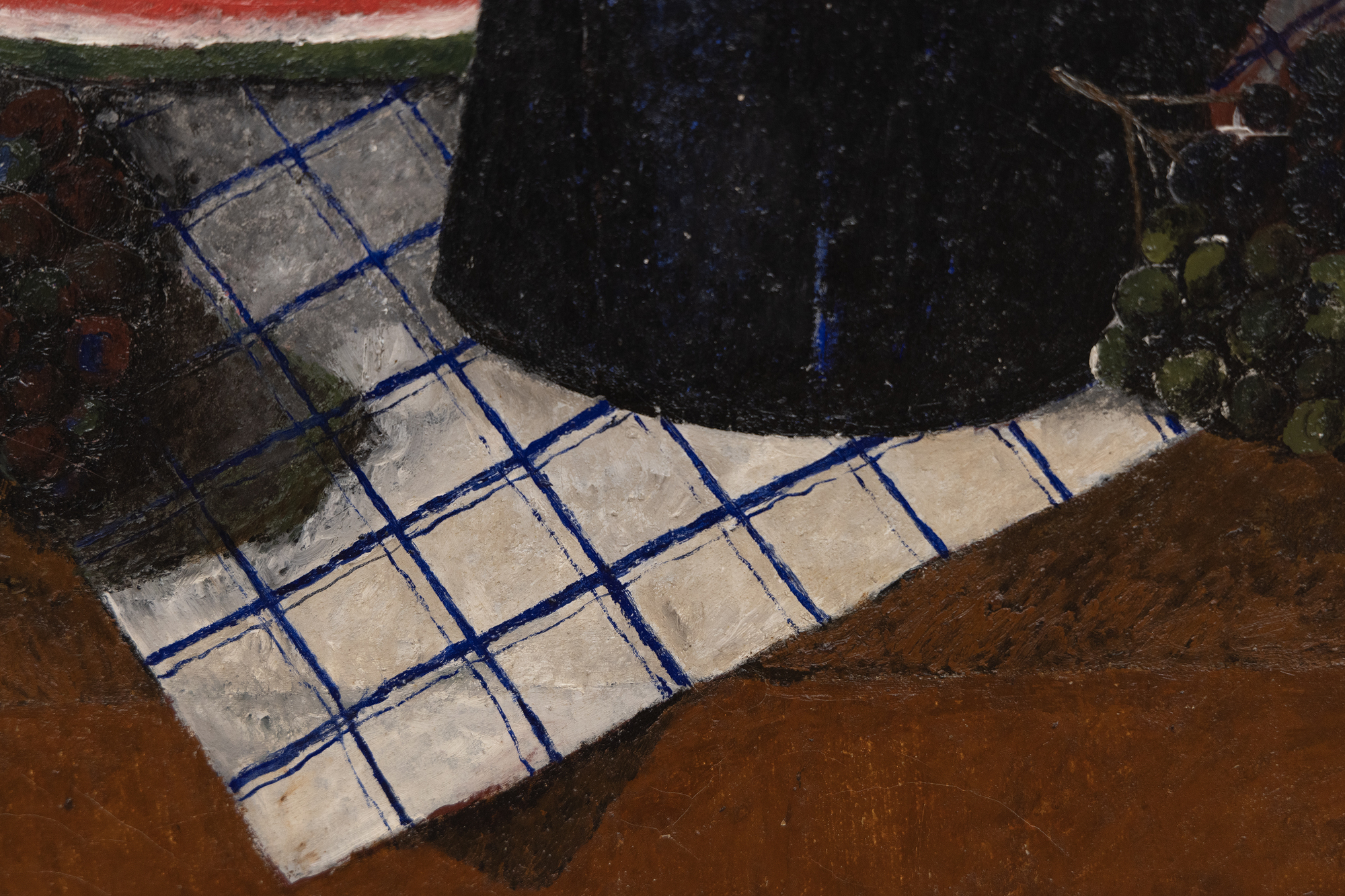

Wie Cézanne erhob Tamayo das Genre des Stilllebens zu einigen seiner schönsten und einfachsten Ausdrucksformen. Dennoch liegt der Leichtigkeit, mit der Tamayo lebendige mexikanische Motive mit den avantgardistischen Einflüssen der Pariser Schule verbindet, ein hohes Maß an Raffinesse zugrunde. Wie die Naturaleza Muerta von 1935 zeigt, weigerte sich Tamayo, in die bloße Dekoration zu verfallen, die oft die zeitgenössische Pariser Schule kennzeichnet, mit der sein Werk verglichen wird. Stattdessen erinnert sein Arrangement von Wassermelonen, Flaschen, einer Kaffeekanne und anderen Gegenständen, die in einer nüchternen, erdgebundenen Tonalität und einem unbestimmten, flachen Raum inszeniert sind, an Tamayos frühes Interesse am Surrealismus. Eine überlagerte quadratische Matrix unterstreicht den Kontrast zwischen den organischen Motiven des Gemäldes und der abstrakten, intellektualisierten Struktur, die ihnen aufgezwungen wird, und vertieft die Interpretation der Erforschung der visuellen Wahrnehmung und Darstellung durch den Künstler. Auf diese Weise dient das Raster dazu, zwischen der sichtbaren Welt und den zugrunde liegenden Strukturen, die unser Verständnis von ihr bestimmen, zu navigieren, und lädt den Betrachter dazu ein, das Wechselspiel zwischen Realität und Abstraktion, Empfindung und Analyse zu betrachten.

WICHTIGE FAKTEN

- Indem er sich auf die Vitalität der Populärkultur konzentrierte, erfasste Rufino Tamayo die wesentliche mexikanische Identität, die universellen künstlerischen Werten Vorrang vor expliziten sozialen und politischen Kommentaren einräumte. Dieser Ansatz unterstreicht sein Engagement für die Neudefinition der mexikanischen Kunst auf der Weltbühne und hebt seine innovativen Beiträge zum Dialog mit der Moderne hervor.

- Wie Cézanne erhob Tamayo das Genre des Stilllebens zu einigen seiner schönsten und einfachsten Ausdrucksformen. Dennoch liegt der Leichtigkeit, mit der Tamayo lebendige mexikanische Motive mit den avantgardistischen Einflüssen der Pariser Schule verbindet, ein hohes Maß an Raffinesse zugrunde.

- Wie Naturaleza Muerta von 1935 zeigt, weigerte sich Tamayo, in die bloße Dekoration zu verfallen, die oft die zeitgenössische Pariser Kunstschule kennzeichnet, mit der sein Werk verglichen wird. Stattdessen erinnert sein Arrangement von Wassermelonen, Flaschen, einer Kaffeekanne und anderen Gegenständen in einer nüchternen, erdgebundenen Tonalität und einem unbestimmten, flachen Raum an Tamayos frühes Interesse am Surrealismus.

MARKTEINBLICKE

- Dieses Gemälde wurde in 9 Büchern veröffentlicht und in 3 Museen ausgestellt.

- 10 Werke von Tamayo haben bei einer Auktion die 3-Millionen-Dollar-Marke überschritten (siehe unten), und 2 davon waren Wassermelonenbilder ("sandías").

- Nach Angaben von Art Market Research mit Sitz in London sind die Marktpreise von Tamayo seit 1976 jährlich um 7,5 % gestiegen (siehe AMR-Grafik).

- Zehn Gemälde von Tamayo haben bei Auktionen mehr als 3 Millionen USD erzielt.

- Mehrere Spitzenverkäufe wurden für Gemälde mit aufgeschnittener Wassermelone erzielt.