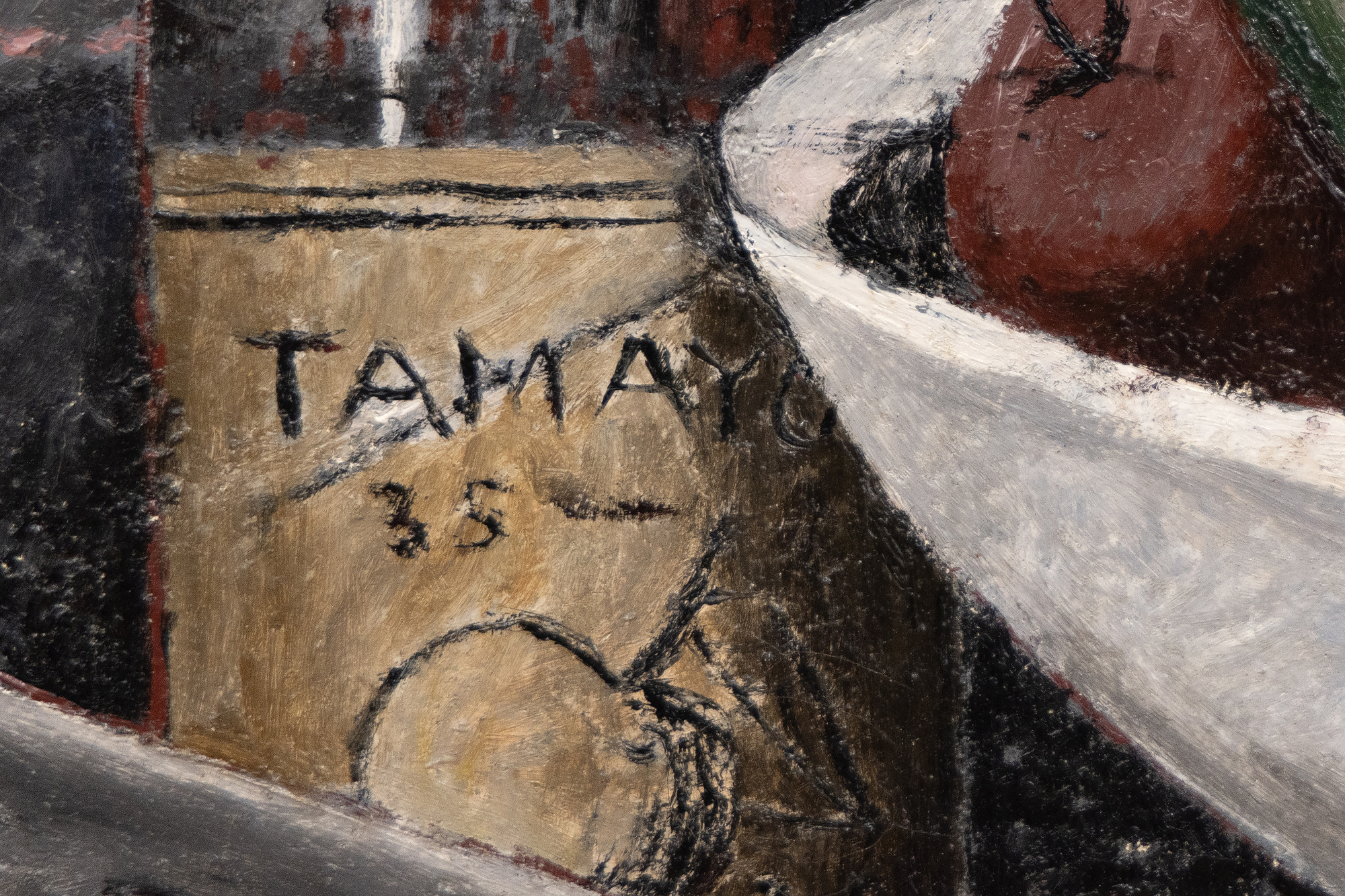

鲁菲诺·塔马约恩(1899-1991)

种源

爱德华-乔多罗夫收藏,加利福尼亚州比佛利山庄范妮-布莱斯小姐收藏集,加利福尼亚州洛杉矶

玛丽-安妮-马丁美术馆,纽约

私人收藏

私人收藏,后裔

展会信息

日本名古屋,名古屋市立美术馆,"鲁菲诺-塔马约回顾展",1993 年 10 月至 12 月 12 日墨西哥,墨西哥城,Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo,"Rufino Tamayo del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 -1950",1996 年 10 月 19 日至 2 月 25 日

加利福尼亚州圣巴巴拉,圣...更。。。塔玛约艺术博物馆,"塔玛约:重新诠释的现代偶像",2007 年 2 月 17 日至 5 月 27 日

文学

"今天,鲁菲诺-塔马约在 Pasaje América 的展览开幕",《环球报》,1935 年 11 月(图文并茂)罗伯特-戈德华特,《鲁菲诺-塔马约》,纽约州纽约市,1947 年,第 XVI 页(第 56 页有插图)。

Justino Fernández、Rufino Tamayo,墨西哥墨西哥城,1948 年

Ceferino Palencia,Rufino Tayamo,墨西哥,墨西哥城,1950 年,第 4 号。4 (有插图)

名古屋市立美术馆,Rufino Tamayo 回顾展,名古屋,日本,1993 年,编号 17,第 34 页(彩色插图)。

Fundación Cultural Televisa & Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo, Rufino Tamayo: del Reflejo al Sueño 1920 - 1950, Mexico City, Mexico, 1995, no.56,第 46 页(彩色插图)

Octavio Paz,Transfiguraciones en Historia del Arte de Oaxaca,墨西哥,墨西哥城,1998 年,第 5 页,第 16-17 页(彩色插图)。5,第 16-17 页(彩色插图)

奥克塔维奥-帕斯,《鲁菲诺-塔马约》,墨西哥,墨西哥城,2003 年,第 5 号。5 (彩色插图)

Diana C.杜邦、胡安-卡洛斯-佩雷达等,《塔马约;重新诠释的现代偶像》,加利福尼亚州圣巴巴拉,2007 年,图 43,第 162 页(彩色插图)。

...少。。。 价格1,850,000

历程

20 世纪 20 年代中期,鲁菲诺-塔马约开始了作为一名成熟的当代色彩画家的关键发展阶段。在纽约,他接触到毕加索、布拉克和乔治-德-基里科的开创性作品,以及立体主义的持久影响。他从街景、流行文化和日常生活中汲取素材,探索绘画和造型的价值,开始形成自己独特的色彩和造型方法。这是向世界性美学的关键转变,使他有别于墨西哥壁画运动的政治叙事所倡导的民族主义狂热。通过关注大众文化的生命力,他捕捉到了墨西哥的本质特性,将普遍的艺术价值置于明确的社会和政治评论之上。这种方法强调了他在全球舞台上重新定义墨西哥艺术的承诺,并突出了他对现代主义对话的创新贡献。

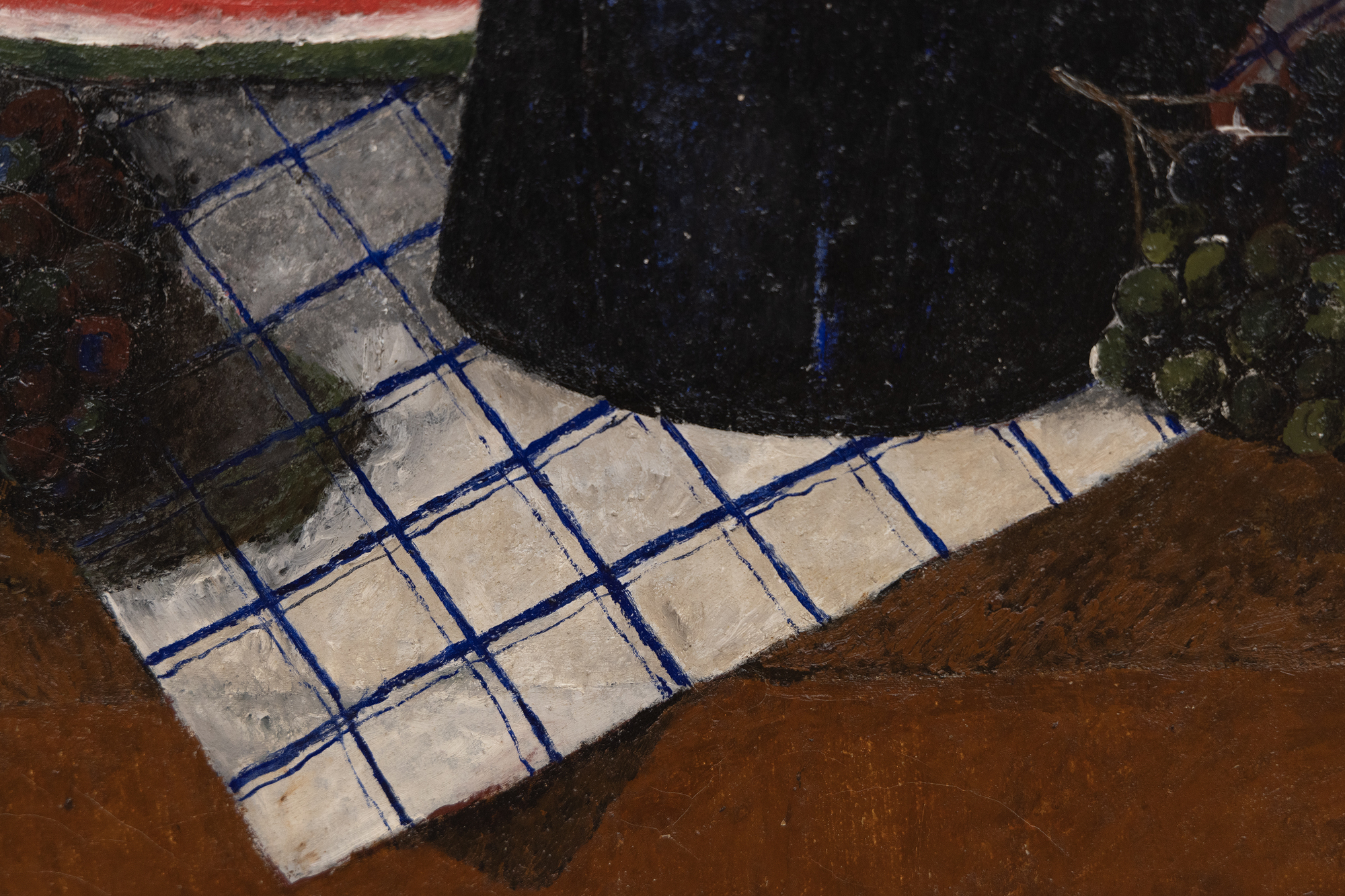

与塞尚一样,塔马约也将静物画提升到了最简洁优美的表现形式。然而,塔马约将充满活力的墨西哥主题与巴黎画派的前卫影响轻松地融为一体,其背后蕴含着高度的复杂性。正如 1935 年的《Naturaleza Muerta》所揭示的那样,塔马约拒绝陷入单纯的装饰,他的作品往往是当代巴黎画派艺术的特征,而他的作品则与巴黎画派相媲美。相反,他将西瓜、瓶子、咖啡壶和其他杂物摆放在一个清醒、朴实的色调和不确定的浅空间中,让人想起塔马约早期对超现实主义的兴趣。叠加的方形矩阵强调了画中有机主题与强加于其上的抽象、知识化结构之间的对比,加深了对艺术家探索视觉感知和表现的诠释。通过这种方式,网格在可视世界与指导我们理解世界的底层结构之间起到了导航作用,吸引观众思考现实与抽象、感觉与分析之间的相互作用。

重要事实

- 通过关注大众文化的活力,鲁菲诺-塔马约捕捉到了墨西哥的基本特征,将普遍的艺术价值置于明确的社会和政治评论之上。这种方法强调了他在全球舞台上重新定义墨西哥艺术的承诺,并突出了他对现代主义对话的创新贡献。

- 与塞尚一样,塔马约也将静物画提升到了最简洁优美的表现形式。然而,塔马约将充满活力的墨西哥图案与巴黎画派的前卫影响轻松地融合在一起,体现了高度的精致。

- 正如 1935 年的《Naturaleza Muerta》所揭示的那样,塔马约拒绝陷入单纯的装饰之中,他的作品与当代巴黎艺术流派的作品经常相提并论。相反,他将西瓜、瓶子、咖啡壶和其他杂物摆放在一个令人清醒、朴实的色调和不确定的浅空间中,让人想起塔马约早期对超现实主义的兴趣。

市场情报

- 这幅画已在 9 本书中出版,并在 3 个博物馆展出。

- 有 10 件塔马约艺术品的拍卖价格超过了 300 万美元大关(见下文),其中 2 件是以西瓜为主题的作品("sandías")。

- 根据伦敦艺术市场研究公司(Art Market Research)的数据,自 1976 年以来,塔马约的市场价格年复合增长率为 7.5%(见 AMR 图表)。

- 塔马约的十幅画作在拍卖会上拍出了 300 多万美元的高价。

- 多幅以切片西瓜为主题的画作销量最高。

最佳拍卖结果

拍卖会上售出的同类画作

博物馆收藏的画作

其他资源

鲁菲诺-塔马约,作者:格雷戈里奥-卢克

鲁菲诺-塔马约--他的艺术源泉

材料与记忆:MIXOGRAFIA 和 TAMAYO

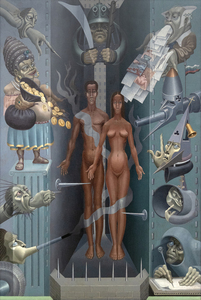

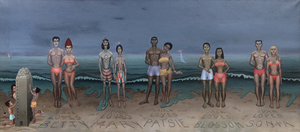

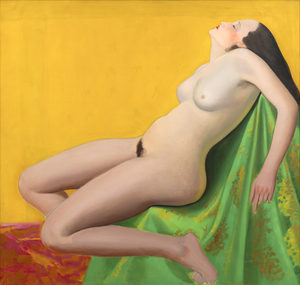

图片库

询问

你可能也喜欢

,_new_mexico_tn40147.jpg )