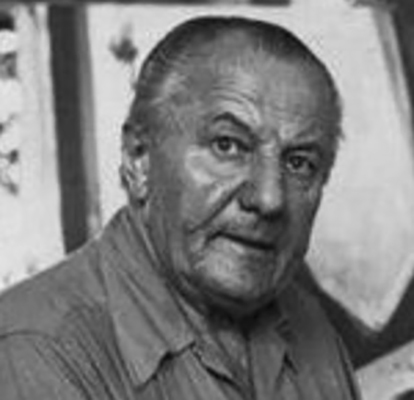

HANS HOFMANN (1880-1966)

Hans Hofmann is one of the most important figures of postwar American art. German born, he played a pivotal role in the development of Abstract Expressionism as an influential teacher of generations of artists in both Germany and America.

Hans Hofmann is one of the most important figures of postwar American art. German born, he played a pivotal role in the development of Abstract Expressionism as an influential teacher of generations of artists in both Germany and America.

Born in Bavaria and educated in Munich, Hofmann studied science and mathematics before studying art. Moving to Paris in 1904, he studied at both the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere and the Academie Colarossi and was influenced by Picasso, Braque, Delaunay, Leger and Matisse, many of whom he met and became friendly. Hofmann moved back to Munich after WWI and opened an innovative art school, transmitting what he learned from the avant-garde in Paris and attracting students from Europe and the United States.

In 1930 Hofmann went to teach at the University of Berkeley and in 1932 settled in New York where he taught art at the Art Students League and later again opened his own schools in Manhattan and Provincetown, Mass. For eager young American artists constrained by the aftermath of WWII and the Depression, contact with Hofmann served as an invaluable connection with European Modernism. Noted art historian Clement Greenberg called Hofmann "in all probability the most important art teacher of our time." His school remained a vital presence in the New York art world until 1958 when the then seventy-eight year old Hofmann decided to devote himself full-time to painting.

Combining Cubist structure and intense Fauvist color, Hofmann created a highly personal visual language, continuously exploring pictorial structures, spatial illusion and chromatic relationships and creating volume through contrasts of color, shape and surface. Also a prominent writer on modern art, his push/pull theory is a culmination of many of his ideas and describes the plasticity of three-dimensionality translated into two-dimensionality. Due to a dazzling burst of creative energy when he was close to 70 years old, his most highly recognizable canvases are from the late 1950’s and 1960’s, paintings of stacked, overlapping and floating rectangles and clear, saturated hues that assured his reputation and cemented him as a key member of the Abstract Expressionists.