جورجيا أوكيف وناسبز(1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

الاصل

مكان أمريكي، نيويوركالسيد والسيدة ماكس أسكولي، نيويورك، 1944

ينحدر من عائلة

هارولد دايموند، نيويورك، عام 1975

معرض جيرالد بيترز، سانتا في، نيو مكسيكو

غاليري إيلين هورويتش، سكوتسديل، أريزونا، 1978

مجموعة من السيد والسيدة إي باري توماس، لاس فيغاس، نيفادا، 1978

مجموعة خاصة، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا

مجموعة خاصة، الولايات المتحدة

معرض

نيويورك، نيويورك، نيويورك، مكان أمريكي، جورجيا أوكيفي، لوحات - 1943، 11 يناير - 11 مارس 1944، رقم 8ويست بالم بيتش... اكثر... فلوريدا، حدائق آن نورتون للنحت، حدائق آن نورتون للنحت، اكتشاف الإبداع: أساتذة الفن الأمريكي، من 10 يناير إلى 17 مارس 2024

الادب

لاينز ، باربرا بوهلر ، جورجيا أوكيفي ، كتالوج رايسونيه المجلد الثاني (نيو هافن ولندن: مطبعة جامعة ييل ، 1999) ، قطة. العدد 1066، الصفحة 670.... اقل...

التاريخ

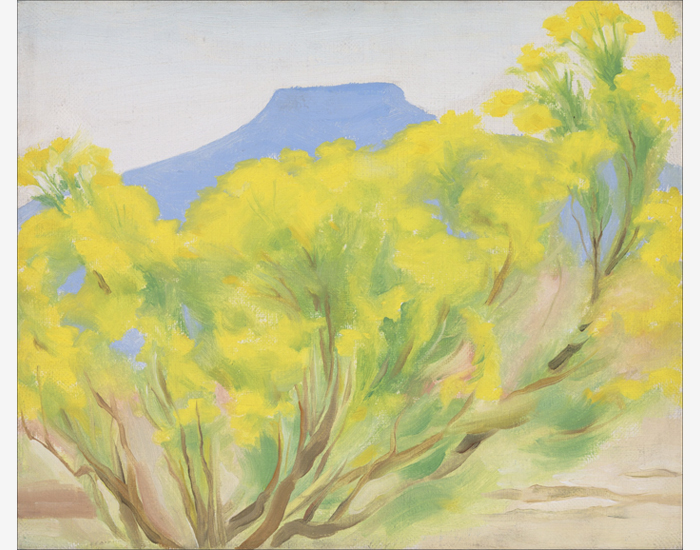

شجرة القطن (بالقرب من أبيكيو) ، نيو مكسيكو ( 1943) للفنانة الأمريكية الشهيرة جورجيا أوكيفي هي مثال على الأسلوب الأكثر تهوية وطبيعية الذي ألهمته الصحراء فيها. كان لدى أوكيفي ميل كبير للجمال المميز للجنوب الغربي ، وجعلها منزلها هناك بين الأشجار المغزلية ، والآفاق الدرامية ، وجماجم الحيوانات المبيضة التي رسمتها كثيرا. أقام أوكيفي في مزرعة الأشباح ، وهي مزرعة متأنقة على بعد اثني عشر ميلا خارج قرية أبيكيو في شمال نيو مكسيكو ورسم شجرة القطن هذه هناك. إن الأسلوب الأكثر نعومة الذي يليق بهذا الموضوع هو خروج عن مناظرها المعمارية الجريئة وزهورها ذات اللون المجوهر.

يتم تجريد شجرة خشب القطن إلى بقع ناعمة من الخضر الخضرة التي من خلالها ينظر إلى فروع أكثر تحديدا ، وتصاعد في الفضاء ضد جيوب السماء الزرقاء. النمذجة من الجذع والطاقة الحساسة في الأوراق تحمل إلى الأمام التجارب الماضية مع الأشجار الإقليمية في الشمال الشرقي التي أسرت أوكيف سنوات في وقت سابق: القيقب والكستناء والأرز والحور، من بين أمور أخرى. اثنين من اللوحات الدرامية من عام 1924، أشجار الخريف، والقيقب والرمادي الكستناء، هي حالات مبكرة من المركزية الغنائية والحازمة، على التوالي. كما رأينا في هذه اللوحات شجرة في وقت مبكر، مبالغة أوكيف حساسية موضوعها مع اللون والشكل.

اكثررؤى السوق

وفقًا للرسم البياني الذي أعدته مؤسسة أبحاث سوق الفن، ارتفعت أسعار سوق جورجيا أوكيفي بمعدل عائد سنوي مركب بنسبة 12.7% منذ عام 1976.

تم تسجيل رقم قياسي في مزاد جورجيا أوكيفي في عام 2014 مع بيع لوحة " جيمسون ويد/زهرة بيضاء رقم 1 " بمبلغ يزيد عن 44.4 مليون دولار أمريكي. ولا يزال هذا أعلى مبلغ مدفوع لفنانة في مزاد علني.

حتى عندما شهد سوق O'Keeffe تراجعا طفيفا خلال الوباء في عام 2020 (كما هو موضح في الرسم البياني AMR) ، يظهر مؤشر ArtPrice العالمي لدوران المزادات أن O'Keeffe ارتفع من المرتبة 263 إلى المرتبة 63 للفنان الأعلى مبيعا في ذلك العام ، مما يوضح أن لوحات O'Keeffe لا تزال في الطلب المتزايد ، خاصة عند مقارنتها بأداء الفنانين الآخرين خلال نفس الوقت.

- في المتوسط على مدى السنوات الأربعين الماضية، تُعرض حوالي 4 لوحات فقط لأوكيفي للبيع في مزاد علني كل عام.

أفضل النتائج في المزاد

"عشبة جيمسون/زهرة بيضاء رقم. 1" (1932) بيعت بمبلغ 44,405,000 دولار أمريكي.

بيعت لوحة "الوردة البيضاء مع زهرة اللاركسبور رقم 1" (1927) بمبلغ 26,725,000 دولار أمريكي.

بيعت لوحة "Black Iris VI" (1936) بمبلغ 21,110,000 دولار أمريكي.

بيعت "Autumn Leaf II" (1927) بمبلغ 15,275,000 دولار أمريكي.

لوحات مماثلة تباع في مزاد علني

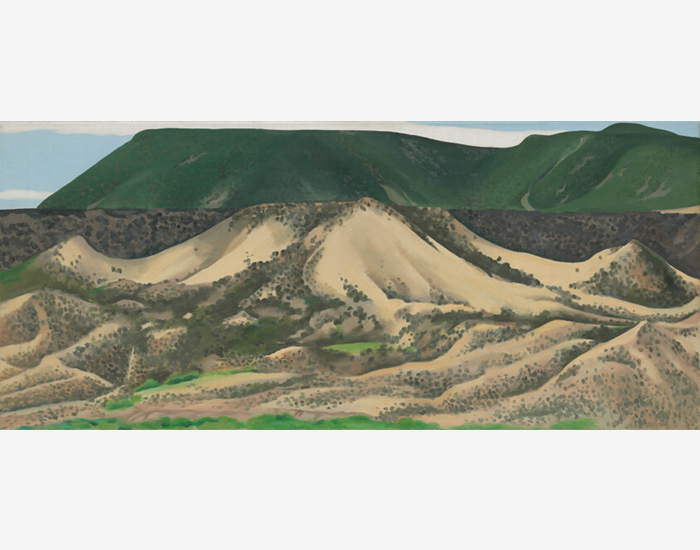

"التلال الحمراء مع Pedernal ، السحب البيضاء" (1936) بيعت مقابل 12،298،000 دولار.

- منظر أوسع للمناظر الطبيعية الصحراوية ، تم بيع هذه اللوحة في مزاد مجموعة المؤسس المشارك لشركة Microsoft Paul Allen

- غالبا ما كانت الطبيعة موضوع فن O'Keeffe ، ويمكن رؤية بعض أشجار القطن على مسافة هذا المشهد.

"بحيرة جورج مع البتولا الأبيض" (1921) بيعت مقابل 11،292،000 دولار.

- بيعت هذه اللوحة المبكرة ذات الموضوع المماثل ، على الرغم من صغر حجمها ، بأكثر من 11.2 مليون دولار في عام 2018 ، وهو ثالث أعلى سعر مزاد لأوكيف

- كانت مواضيع الطبيعة ، وخاصة الأشجار ، محور تركيز متكرر لأوكيف

"بالقرب من أبيكيو ، نيو مكسيكو" (1931) بيعت مقابل 8،412،500 دولار.

- عمل أصغر من شجرة كوتونوود (بالقرب من أبيكيو)، نيو مكسيكو

- منظر طبيعي سابق من نفس المنطقة في نيو مكسيكو ، بيعت هذه القطعة بأكثر من 8.4 مليون دولار في عام 2018

"القيقب الأحمر في بحيرة جورج" (1926) بيعت مقابل 8،187،500 دولار.

- هذا الموضوع طبيعة أوكيف من نفس الحجم تباع في عام 2018 لأكثر من 8.18 مليون دولار

- مثال سابق من عام 1926

"أشكال الطبيعة - Gaspé" (1931) بيعت مقابل 6،870،200 دولار.

- موضوع الطبيعة المجردة على نطاق صغير

- بيعت مؤخرا لأكثر من 6.87 مليون دولار

الندرة

- 43٪ من لوحات O'Keeffe محفوظة بالفعل في مجموعات المتاحف.

- ومن أصل 616 عملاً من الأعمال الزيتية على القماش التي رسمتها أوكيفي والبالغ عددها 616 عملاً زيتياً على القماش، لا يزال أقل من 300 عمل متاحاً للمجموعات الخاصة.

- مع مرور الوقت ، سيتم توريث العديد من لوحات O'Keeffe الموجودة حاليا في مجموعات خاصة للمتاحف ، تاركة القليل جدا منها متاحا على الإطلاق.

- رسمت أوكيفي أشجار خشب القطن لأول مرة في أبيكيو لمدة عامين فقط، من 1943 إلى 1945، ورسمت 9 لوحات فقط لهذه السلسلة الأساسية. منها 6 لوحات محفوظة في مجموعات المتاحف الدائمة، ولم يتبق منها سوى 3 لوحات في أيدي القطاع الخاص.

- يمكن العثور على لوحات أوكيفي " أشجار كوتونوود " - من السلسلة الأساسية الأصلية 1943-1945 ومن السنوات اللاحقة - في مجموعات المتاحف الرائدة بما في ذلك متحف جورجيا أوكيفي ومعهد بتلر للفنون الأمريكية ومتحف الفنون الجميلة في بوسطن.

لوحات من أخشاب القطن والأشجار و Abiquiu في مجموعات المتحف

متحف جورجيا أوكيفي، سانتا في

متحف سانتا باربرا للفنون

متحف جورجيا أوكيفي، سانتا في

معهد بتلر للفن الأمريكي، أوهايو

متحف جورجيا أوكيفي، سانتا في

متحف كليفلاند للفنون

متحف دالاس للفنون

متحف نيو مكسيكو للفنون ، سانتا في

متحف الفنون الجميلة ، بوسطن

متحف بروكلين، نيويورك

متحف المتروبوليتان للفنون، نيويورك

متحف ويتني للفن الأمريكي، نيويورك

متحف جورجيا أوكيفي، سانتا في

متحف كليفلاند للفنون

معهد الفنون في شيكاغو

معرض الصور

موارد إضافية

المصادقه

تم إدراج شجرة كوتونوود (بالقرب من أبيكيو) ، نيو مكسيكو ، 1943 كرقم 1066 في كتالوج باربرا بوهلر لاينز لأعمال جورجيا أوكيفي الفنية. اللوحة موضحة في الصفحة 670 من المجلد الثاني.

انظر كتالوج Raisonné

الاستفسار

قد تحب أيضا