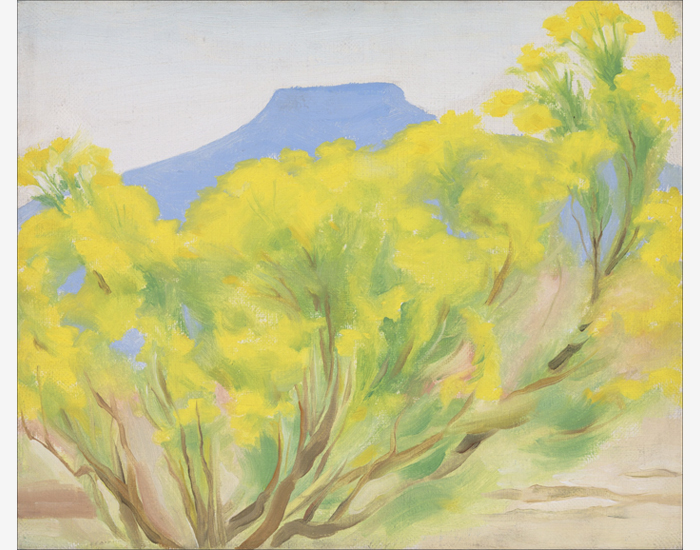

GEORGIA O'KEEFFE (1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

种源

美国的一个地方,纽约马克斯-阿斯科利先生和夫人,纽约,1944年

家族中的后裔

哈罗德-戴蒙德,纽约,约1975年

杰拉尔德-彼得斯画廊,圣菲,新墨西哥州

伊莱恩-霍里奇画廊,斯科茨代尔,亚利桑那州,1978年

E. Parry Thomas先生和夫人的收藏,拉斯维加斯,内华达,1978年

私人收藏,美国

展会信息

纽约,纽约,美国地方,乔治亚·奥基夫,绘画 – 1943 年,1944 年 1 月 11 日至 3 月 11 日,第 8 期佛罗里达西棕榈滩,安诺顿雕塑花园,Discoveri...更。。。ng 创造力:美国艺术大师,2024 年 1 月 10 日至 3 月 17 日

文学

Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Catalogue Raisonné Volume Two (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), cat.第1066号,第670页。...少。。。

历程

美国知名艺术家乔治亚-奥基夫(Georgia O'Keeffe)的《木棉树(靠近Abiquiu),新墨西哥州 》(1943年)是沙漠给她带来的更大气、更自然风格的典范之作。O'Keeffe对西南地区的独特之美情有独钟,她把家安在了她经常画的那些骨瘦如柴的树木、戏剧性的远景和漂白的动物头骨之间。奥基夫住在幽灵牧场,一个位于新墨西哥州北部Abiquiú村外12英里的花花公子牧场,并在那里画了这棵木棉树。与这一主题相适应的柔和风格与她大胆的建筑景观和宝石色调的花朵有所不同。

木棉树被抽象成柔和的绿色斑块,透过这些绿色斑块可以看到更多的树枝,在蓝天的衬托下在空间中盘旋。树干的造型和树叶的微妙能量延续了过去对东北地区树木的实验,这些树木多年前就吸引了奥基夫:枫树、栗子、雪松和杨树等等。1924年的两幅戏剧性的画作《秋天的树,枫树》和《灰色的栗子》,分别是抒情和坚决的中心思想的早期实例。从这些早期的树画中可以看出,奥基夫用色彩和形式夸大了她的主题的感性。

更市场情报

根据艺术市场研究公司绘制的图表,自 1976 年以来,乔治亚-奥基弗的市场价格以 12.7% 的复合年回报率增长。

乔治亚-奥基夫的拍卖纪录是在 2014 年以《Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1》超过 4440 万美元的价格创下的。这仍然是女艺术家在拍卖会上的最高成交价。

即使在2020年大流行期间,奥基夫的市场略有下滑(如AMR图所示),ArtPrice的全球拍卖成交额指数显示,奥基夫在那一年从第263位上升到销量最高的艺术家第63位,说明奥基夫的画作仍然有越来越大的需求,尤其是与其他艺术家在同一时期的表现相比。

- 在过去的 40 年里,平均每年大约只有 4 幅奥基弗的画作在拍卖会上出售。

拍卖会的最高结果

"Jimson weed/ White flower no.1"(1932 年)的成交价为 4,405,000 美元。

"White Rose with Larkspur No.I"(1927 年)以 2,672.5 万美元成交。

"黑鸢六号"(1936 年)以 2,110,000 美元的价格售出。

"秋叶 II》(1927 年)以 1527.5 万美元成交。

同类拍卖的画作

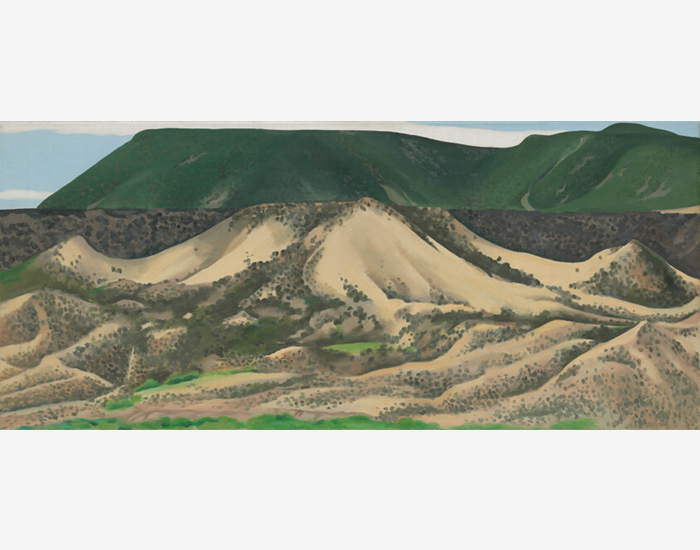

"红山白云》(1936年)以1229.8万美元成交。

- 更广阔的沙漠景观,这幅画在微软联合创始人保罗-艾伦的收藏品拍卖会上售出

- 大自然常常是奥基夫的艺术主题,在这幅风景画的远处可以看到一些木棉树。

"乔治湖与白桦树"(1921年)以11,292,000美元成交。

- 这幅题材相似的早期画作,虽然规模较小,但在2018年以超过1120万美元的价格成交,是奥基夫的第三高拍卖价。

- 自然题材,尤其是树木,是奥基夫经常关注的焦点。

"新墨西哥州阿比丘附近"(1931年)以841.25万美元成交。

- 比木棉树更小的作品(靠近Abiquiu),新墨西哥州

- 一幅来自新墨西哥州同一地区的早期风景画,这幅作品在2018年以超过840万美元的价格售出

"乔治湖的红枫"(1926年)以818.75万美元成交。

- 这幅同样大小的奥基夫自然题材作品在2018年以超过818万美元的价格成交。

- 1926年的较早例子

"自然形态-加斯佩"(1931年)以687.02万美元成交。

- 小规模、抽象的自然主题

- 最近以超过687万美元售出

疤痕

- 奥基夫43%的画作已经被博物馆收藏。

- 在奥基芙创作的 616 幅布面油画作品中,只有不到 300 幅被私人收藏。

- 随着时间的推移,许多目前由私人收藏的奥基夫的画作将被遗赠给博物馆,留下的画作将很少有机会。

- 从 1943 年到 1945 年,奥基弗仅用了两年时间首次在阿比奎为木棉树作画,并且仅为这个核心系列创作了 9 幅作品。其中 6 幅被博物馆永久收藏,只有 3 幅由私人收藏。

- 欧姬芙的《木棉树》(CottonwoodTrees),包括 1943-1945 年最初的核心系列和后来的作品,均被乔治亚-欧姬芙博物馆、巴特勒美国艺术学院和波士顿美术馆等知名博物馆收藏。

博物馆收藏的木棉、树木和阿比丘的绘画作品

乔治亚-奥基夫博物馆,圣菲

圣巴巴拉艺术博物馆

乔治亚-奥基夫博物馆,圣菲

巴特勒美国艺术学院,俄亥俄州

乔治亚-奥基夫博物馆,圣菲

克利夫兰艺术博物馆

达拉斯艺术博物馆

新墨西哥艺术博物馆,圣菲

波士顿美术博物馆

布鲁克林博物馆,纽约

大都会艺术博物馆,纽约

惠特尼美国艺术博物馆,纽约

乔治亚-奥基夫博物馆,圣菲

克利夫兰艺术博物馆

芝加哥艺术学院

图片库

其他资源

认证

木棉树(近阿比丘),新墨西哥州,1943年,在Barbara Buhler Lynes的Georgia O'Keeffe的艺术作品目录中被列为1066号。这幅画在第二卷的第670页上有插图。

见《Raisonné目录》。

询问

你可能也喜欢