GEORGIA O'KEEFFE (1887-1986)

,_new_mexico_40147.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail1.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail2.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail3.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail4.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail5.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail6.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail7.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail8.jpg)

,_new_mexico_40147_detail9.jpg)

Provenienz

Ein amerikanischer Ort, New YorkMr. und Mrs. Max Ascoli, New York, 1944

Abstammung in der Familie

Harold Diamond, New York, ca. 1975

Galerie Gerald Peters, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Elaine Horwich Galerie, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1978

Sammlung von Mr. und Mrs. E. Parry Thomas, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1978

Privatsammlung, Los Angeles, Kalifornien

Privatsammlung, Vereinigte Staaten

Ausstellung

New York, New York, An American Place, Georgia O'Keeffe, Gemälde - 1943, 11. Januar - 11. März 1944, Nr. 8West Palm Beach,...Mehr..... Florida, Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens, Entdeckung der Kreativität: Meister der amerikanischen Kunst, 10. Januar - 17. März 2024

Literaturhinweise

Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Catalogue Raisonné Volume Two (New Haven und London: Yale University Press, 1999), Kat. Nr. 1066, S. 670....WENIGER.....

Geschichte

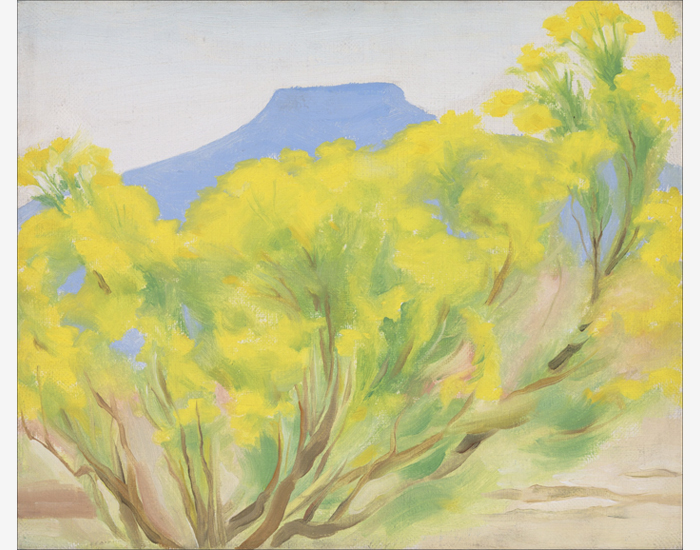

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), New Mexico (1943) der berühmten amerikanischen Künstlerin Georgia O'Keeffe ist ein Beispiel für den luftigeren, naturalistischen Stil, den die Wüste bei ihr inspirierte. O'Keeffe hatte eine große Vorliebe für die unverwechselbare Schönheit des Südwestens und ließ sich dort inmitten der spindeldürren Bäume, dramatischen Ausblicke und gebleichten Tierschädel nieder, die sie so häufig malte. O'Keeffe ließ sich auf der Ghost Ranch nieder, einer Touristenranch zwölf Meilen außerhalb des Dorfes Abiquiú im Norden New Mexicos, und malte dort diesen Pappelbaum. Der weiche Stil, der zu diesem Motiv passt, ist eine Abkehr von ihren kühnen architektonischen Landschaften und juwelenfarbenen Blumen.

Die Pappel wird in weiche Flecken grünen Grüns abstrahiert, durch die sich die Äste besser abgrenzen lassen, die sich spiralförmig im Raum vor dem blauen Himmel bewegen. Die Modellierung des Stammes und die zarte Energie der Blätter knüpfen an frühere Experimente mit den regionalen Bäumen des Nordostens an, die O'Keeffe schon Jahre zuvor fasziniert hatten: Ahorne, Kastanien, Zedern und Pappeln, um nur einige zu nennen. Zwei dramatische Gemälde aus dem Jahr 1924, Autumn Trees, The Maple und The Chestnut Grey, sind frühe Beispiele für eine lyrische bzw. entschlossene Zentralität. Wie in diesen frühen Baumbildern zu sehen ist, übertrieb O'Keeffe die Sensibilität ihres Motivs mit Farbe und Form.

MehrMARKTEINBLICKE

Laut der von Art Market Research erstellten Grafik sind die Marktpreise von Georgia O'Keeffe seit 1976 mit einer durchschnittlichen jährlichen Rendite von 12,7 % gestiegen.

Der Auktionsrekord von Georgia O'Keeffe wurde 2014 mit dem Verkauf von Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 für über 44,4 Millionen US-Dollar aufgestellt. Dies ist nach wie vor die höchste Summe, die bei einer Auktion für eine Künstlerin gezahlt wurde.

Selbst als O'Keeffes Markt während der Pandemie im Jahr 2020 einen leichten Rückgang verzeichnete (wie in der AMR-Grafik zu sehen), zeigt der globale Index der Auktionsumsätze von ArtPrice, dass O'Keeffe in diesem Jahr von Platz 263 auf Platz 63 der meistverkauften Künstler aufstieg, was veranschaulicht, dass O'Keeffes Gemälde nach wie vor gefragt sind, vor allem im Vergleich zur Leistung anderer Künstler in dieser Zeit.

- In den letzten 40 Jahren wurden im Durchschnitt nur etwa 4 Gemälde von O'Keeffe pro Jahr versteigert.

Spitzenergebnisse bei Auktionen

"Stechapfel/ Weiße Blume Nr. 1" (1932) wurde für 44.405.000 USD verkauft.

"Weiße Rose mit Rittersporn Nr. I" (1927) wurde für 26.725.000 USD verkauft.

"Black Iris VI" (1936) wurde für 21.110.000 USD verkauft.

"Autumn Leaf II" (1927) wurde für 15.275.000 USD verkauft.

Vergleichbare Gemälde bei einer Auktion verkauft

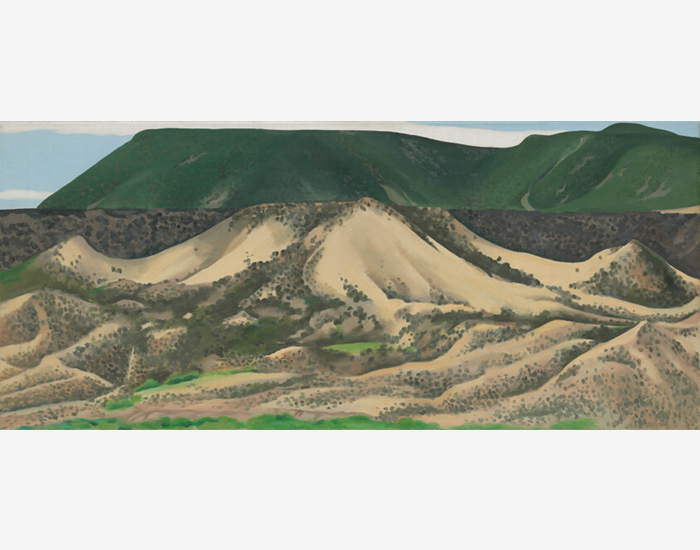

"Red Hills with Pedernal, White Clouds" (1936) wurde für 12.298.000 $ verkauft.

- Dieses Gemälde, das eine größere Ansicht der Wüstenlandschaft zeigt, wurde bei der Versteigerung der Sammlung des Microsoft-Mitbegründers Paul Allen verkauft.

- Die Natur war oft das Thema von O'Keeffes Kunst, und einige Pappeln sind in der Ferne dieser Landschaft zu sehen.

"Lake George With White Birch" (1921) wurde für 11.292.000 Dollar verkauft.

- Diese frühe Leinwand mit ähnlichem Thema, wenn auch in kleinerem Maßstab, wurde 2018 für über 11,2 Millionen Dollar verkauft, der dritthöchste Auktionspreis für O'Keeffe

- Naturmotive, insbesondere Bäume, waren ein häufiges Thema von O'Keeffe

"In der Nähe von Abiquiu, New Mexico" (1931) wurde für 8.412.500 Dollar verkauft.

- Ein kleineres Werk als Cottonwood Tree (bei Abiquiu), New Mexico

- Eine frühere Landschaft aus der gleichen Gegend in New Mexico, die 2018 für über 8,4 Millionen Dollar verkauft wurde.

"The Red Maple at Lake George" (1926) wurde für 8.187.500 Dollar verkauft.

- Dieses Naturmotiv von O'Keeffe in derselben Größe wurde 2018 für über 8,18 Millionen Dollar verkauft.

- Älteres Beispiel aus dem Jahr 1926

"Nature Forms - Gaspé" (1931) wurde für 6.870.200 $ verkauft.

- Kleinformatiges, abstraktes Naturmotiv

- Kürzlich für über $6,87 Millionen verkauft

SCARCITY

- 43 % der Gemälde von O'Keeffe befinden sich bereits in Museumssammlungen.

- Von den 616 Ölgemälden auf Leinwand, die O'Keeffe malte, sind weniger als 300 in Privatsammlungen zu finden.

- Im Laufe der Zeit werden viele der O'Keeffe-Gemälde, die sich derzeit in Privatsammlungen befinden, an Museen vererbt, so dass nur sehr wenige jemals verfügbar sein werden.

- O'Keeffe malte die Cottonwood-Bäume in Abiquiu zunächst nur zwei Jahre lang, von 1943 bis 1945, und schuf nur neun Gemälde für diese zentrale Serie. Von diesen Gemälden befinden sich 6 in ständigen Museumssammlungen, nur 3 sind in Privatbesitz.

- O'Keeffes Cottonwood Trees - aus der ursprünglichen Kernserie von 1943-1945 und aus späteren Jahren - befinden sich in führenden Museumssammlungen wie dem Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, dem Butler Institute of American Art und dem Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Gemälde von Cottonwoods, Bäumen und Abiquiu in Museumssammlungen

Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Kunstmuseum Santa Barbara

Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Das Butler-Institut für amerikanische Kunst, Ohio

Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Das Kunstmuseum von Cleveland

Dallas Museum of Art

New Mexico Museum für Kunst, Santa Fe

Museum der Schönen Künste, Boston

Brooklyn Museum, New York

Das Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Whitney Museum für amerikanische Kunst, New York

Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Das Kunstmuseum von Cleveland

Kunstinstitut Chicago

Bild-Galerie

Zusätzliche Ressourcen

Authentifizierung

Cottonwood Tree (Near Abiquiu), New Mexico, 1943 ist als Nummer 1066 in Barbara Buhler Lynes' Werkverzeichnis der Kunstwerke von Georgia O'Keeffe aufgeführt. Das Gemälde ist auf Seite 670 des zweiten Bandes abgebildet.

Siehe Raisonné-Katalog

Fragen Sie

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen