ALEXANDER CALDER (1898-1976)

Provenienz

Perls Galerie, New YorkPrivatsammlung, erworben von den oben Genannten

Ausstellung

Crane Gallery, London, Calder: Öle, Gouachen, Mobiles und Wandteppiche, 5. März-1. Mai 1992Geschichte

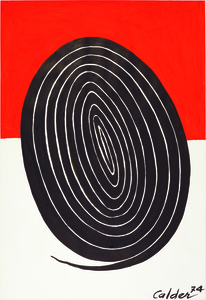

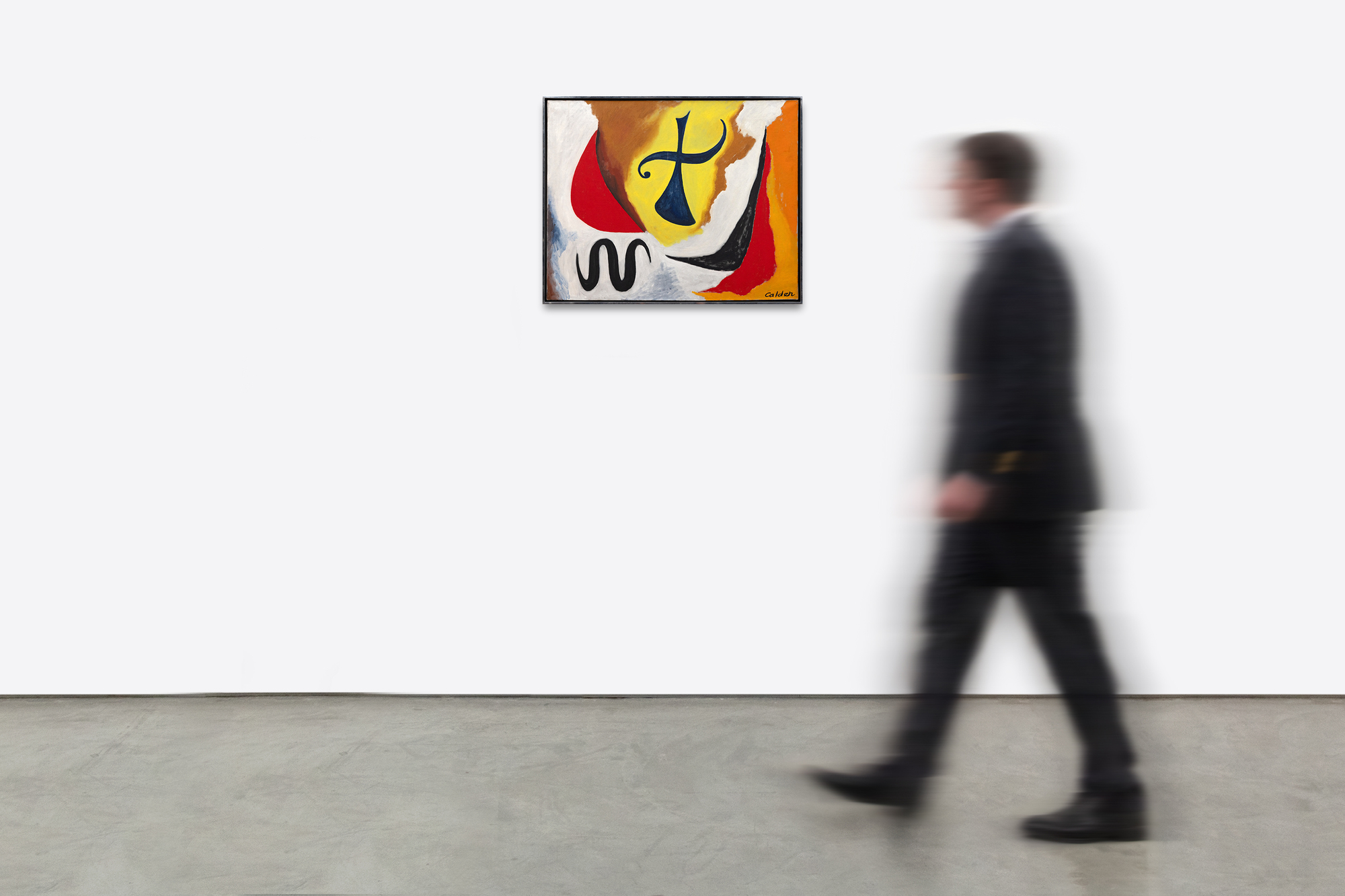

Alexander Calder schuf in der zweiten Hälfte der 1940er und zu Beginn der 1950er Jahre eine überraschende Anzahl von Ölgemälden. Zu dieser Zeit hatte sich der Schock seines Besuchs in Mondrians Atelier im Jahr 1930, bei dem er nicht von den Bildern, sondern von der Umgebung beeindruckt war, zu einer eigenen künstlerischen Sprache Calders entwickelt. Als Calder 1948 Das Kreuz malte, stand er bereits an der Schwelle zur internationalen Anerkennung und war auf dem Weg, 1952 den Großen Preis für Skulptur der XX VI. Biennale von Venedig zu gewinnen. Calder arbeitete an seinen Gemälden in Übereinstimmung mit seiner bildhauerischen Praxis und näherte sich beiden Medien mit der gleichen Formensprache und Beherrschung von Form und Farbe.

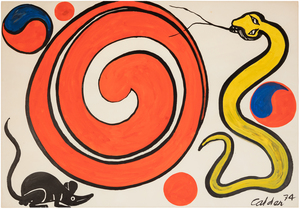

Calder war von den unsichtbaren Kräften, die Objekte in Bewegung halten, zutiefst fasziniert. Indem er dieses Interesse von der Bildhauerei auf die Leinwand übertrug, erzeugte Calder ein Gefühl des Drehmoments in The Cross, indem er die Ebenen und das Gleichgewicht verschob. Mit diesen Elementen erzeugte er eine angedeutete Bewegung, die den Eindruck erweckt, dass die Figur vorwärts drängt oder sogar vom Himmel herabsteigt. Die entschlossene Eigendynamik des Kreuzeswird durch Details wie die nachdrücklich ausgestreckten Arme des Dargestellten, den faustartig geschwungenen Vektor auf der linken Seite und die silhouettierte, schlangenförmige Figur noch verstärkt.

Calder nimmt auch einen starken Faden poetischer Unbekümmertheit durch die Oberfläche von The Crossauf. Es erinnert an die hieratische und ausgesprochen persönliche Bildsprache seines guten Freundes Miró, aber in der effektiven Animation der verschiedenen Elemente dieses Gemäldes ist es ganz Calder. Kein Künstler hat sich mehr poetische Freiheiten erlaubt als Calder, und während seiner gesamten Karriere blieb der Künstler in seinem Verständnis von Form und Komposition flexibel. Er begrüßte sogar die unzähligen Interpretationen anderer und schrieb 1951: "Dass andere begreifen, was ich im Sinn habe, scheint unwesentlich zu sein, zumindest so lange sie etwas anderes im Sinn haben."

In jedem Fall ist es wichtig, sich daran zu erinnern, dass Das Kreuz kurz nach den Wirren des Zweiten Weltkriegs gemalt wurde und für manche eine ernüchternde Reflexion der Zeit zu sein scheint. Vor allem aber beweist das Kreuz, dass Alexander Calder zuerst den Pinsel in die Hand nahm, um Ideen über Form, Struktur, Beziehungen im Raum und vor allem über Bewegung zu entwickeln.

MARKTEINBLICKE

- Die Grafik von Art Market Research mit Sitz in London zeigt, dass der Wert der Kunstwerke von Calder seit Januar 1976 um 3474,3 % gestiegen ist, was einer durchschnittlichen jährlichen Wachstumsrate von 7,6 entspricht.

- Obwohl Calder ein produktiver Künstler war, gehören Ölgemälde wie Das Kreuz zu den seltensten Werken des Künstlers.

Vergleichbare Gemälde bei einer Auktion verkauft

"Personnage" (1946) wurde für 1.865.000 USD verkauft.

- Zwei Jahre vor "Das Kreuz" gemalt

- Ähnliche Farben, aber die Abstraktion in "The Cross" ist besser nachvollziehbar

- Dieses Gemälde, das 2014 versteigert wurde, wäre heute weit über 3 Millionen Dollar wert.

"Fond rouge" (1949) wurde für 1.815.000 USD verkauft.

- Nur ein Jahr nach The Cross gemalt

- Eine schöne Abstraktion, aber kompositorisch nicht so spannend wie The Cross

- Der Hintergrund ist hier nur einfarbig, während das Kreuz mehrere Farbtöne in seinem Hintergrund ausgleicht