היסטוריה

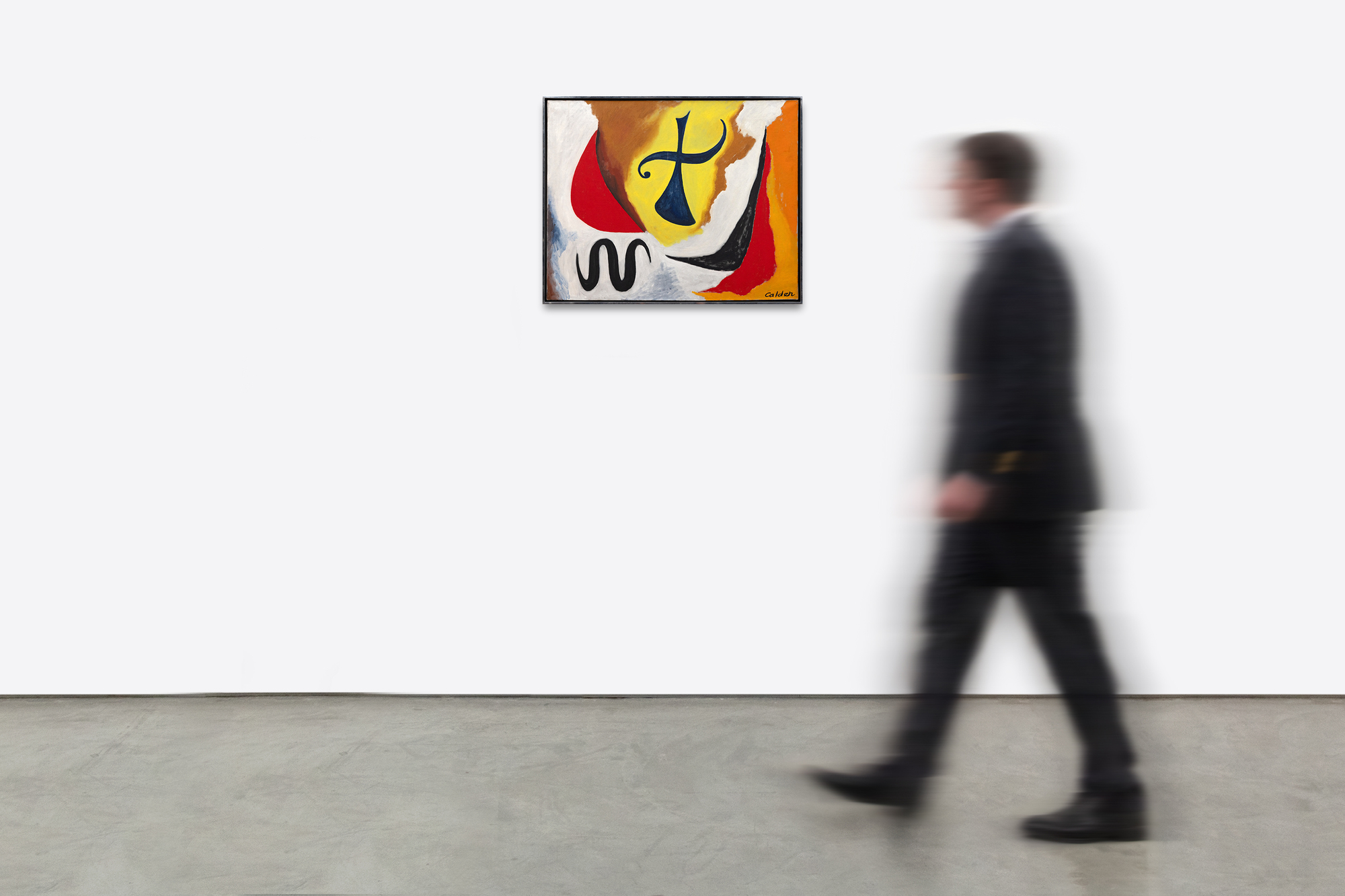

אלכסנדר קאלדר ביצע מספר מפתיע של ציורי שמן במחצית השנייה של שנות ה-40 ותחילת שנות ה-50. בשלב זה, ההלם של ביקורו ב-1930 בסטודיו של מונדריאן, שם התרשם לא מהציורים אלא מהסביבה, התפתח לשפה אמנותית משלו של קאלדר . לכן, כשקאלדר צייר את "הצלב" ב-1948, הוא כבר היה על סף הכרה בינלאומית והיה בדרכו לזכייה בפרס הגדול של הביאנלה של ונציה XX VI לפיסול ב-1952. בעבודה על ציוריו בתיאום עם הפרקטיקה הפיסולית שלו, קאלדר ניגש לשני המדיומים באותה שפה צורנית ושליטה באותה צורה וצבע.

קאלדר הסתקרן עמוקות מהכוחות הבלתי נראים שמחזיקים חפצים בתנועה. אם ניקח את העניין הזה מפיסול לקנבס, נראה שקאלדר בנה תחושה של מומנט בתוך הצלב על ידי הסטת המישורים והאיזון שלו. באמצעות אלמנטים אלה, הוא יצר תנועה מרומזת המרמזת על כך שהדמות לוחצת קדימה או אפילו יורדת מהשמיים שמעל. התנופה הנחושה של הצלב מועצמת עוד יותר על ידי פרטים כגון זרועותיו המושטות בהדגשה של הנושא, וקטור התלתלים דמוי האגרוף משמאל, ודמות הנחש בעל הצללית.

קאלדר גם מאמץ חוט חזק של נטישה פואטית על פני השטח של הצלב. זה מהדהד את השפה החזותית ההיראטית והאישית של חברו הטוב מירו , אבל זה הכל קאלדר באנימציה האפקטיבית של האלמנטים השונים של הציור הזה. אין אמן שזכה לרישיון פואטי יותר מאשר קאלדר, ולאורך כל הקריירה שלו, האמן נשאר גמיש בהבנתו את הצורה והקומפוזיציה. הוא אפילו קידם בברכה את שלל הפרשנויות של אחרים, וכתב ב-1951: "זה שאחרים תופסים את מה שיש לי בראש נראה לא חיוני, לפחות כל עוד יש להם משהו אחר בשלהם".

כך או כך, חשוב לזכור כי הצלב צויר זמן קצר לאחר הטלטלה של מלחמת העולם השנייה ולחלק נראה כהשתקפות מפוכחת של התקופה. יותר מכל, הצלב מוכיח שאלכסנדר קאלדר העמיס את המכחול שלו קודם כדי לעבד רעיונות על צורה, מבנה, יחסים בחלל, והכי חשוב, תנועה.

תובנות שוק

- הגרף של Art Market Research שבסיסו בלונדון מראה כי מאז ינואר 1976, ערך יצירות האמנות של קלדר עלה ב -3474.3%, עם שיעור צמיחה שנתי מורכב של 7.6.

- בעוד שקאלדר היה אמן פורה, ציורי שמן על בד כמו הצלב הם בין הדוגמאות הנדירות ביותר לעבודתו של האמן.

ציורים דומים שנמכרו במכירה פומבית

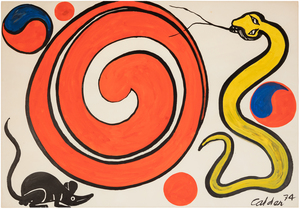

"Personnage" (1946) נמכר ב-1,865,000 דולר.

- צויר שנתיים לפני הצלב

- צבעים דומים, אך ההפשטה בצלב ניתנת יותר להתייחסות

- הציור הזה, שנמכר במכירה פומבית ב-2014, היה שווה היום הרבה יותר מ-3 מיליון דולר

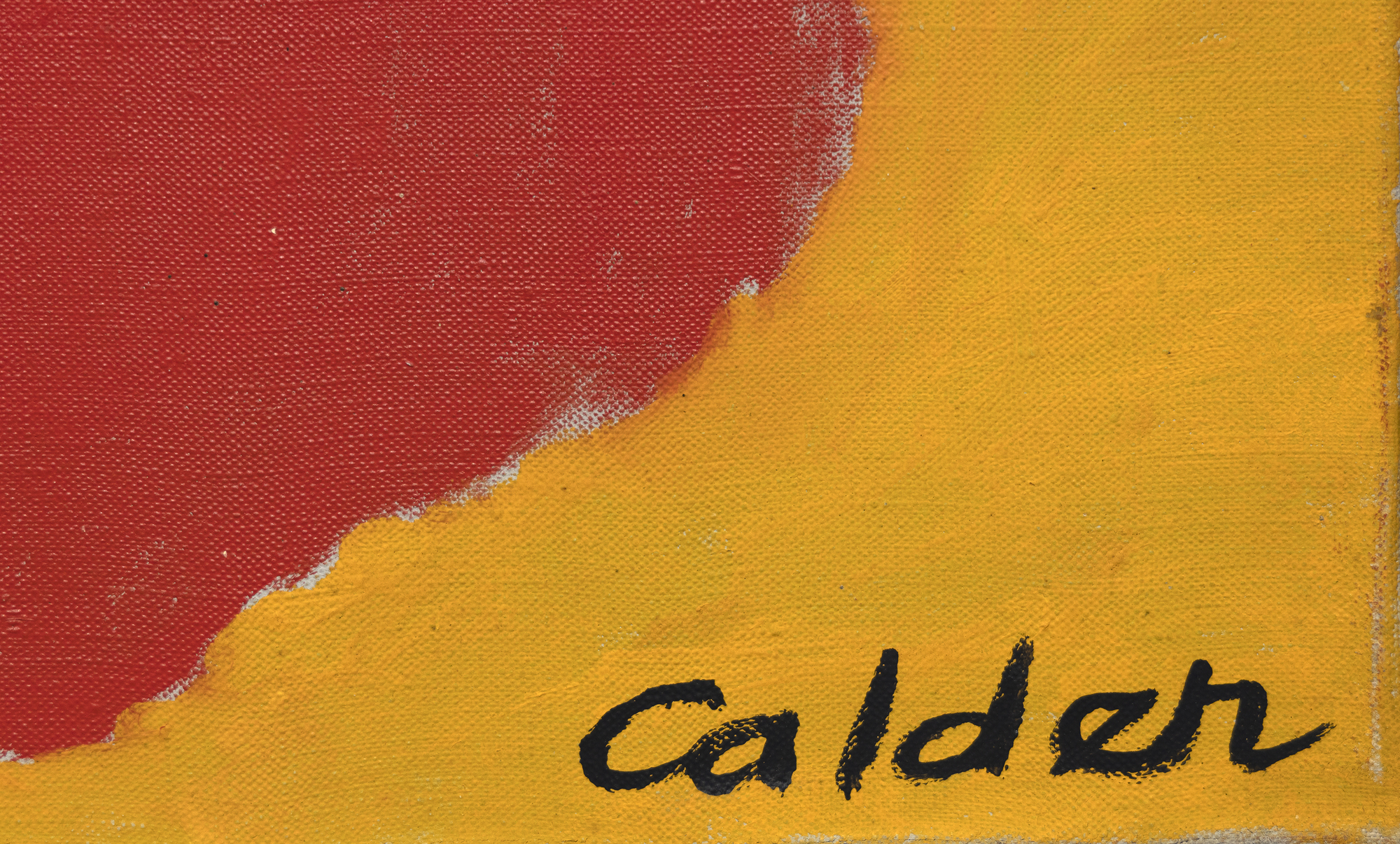

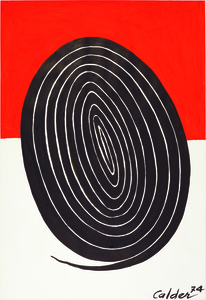

"Fond rouge" (1949) נמכר ב-1,815,000 דולר.

- צויר שנה אחת בלבד לאחר הצלב

- הפשטה נחמדה, אבל לא מרגשת מבחינה קומפוזיציונית כמו הצלב

- הרקע כאן הוא בצבע אחד בלבד, בעוד ש-The Cross מאזן מספר גוונים ברקע שלו