历程

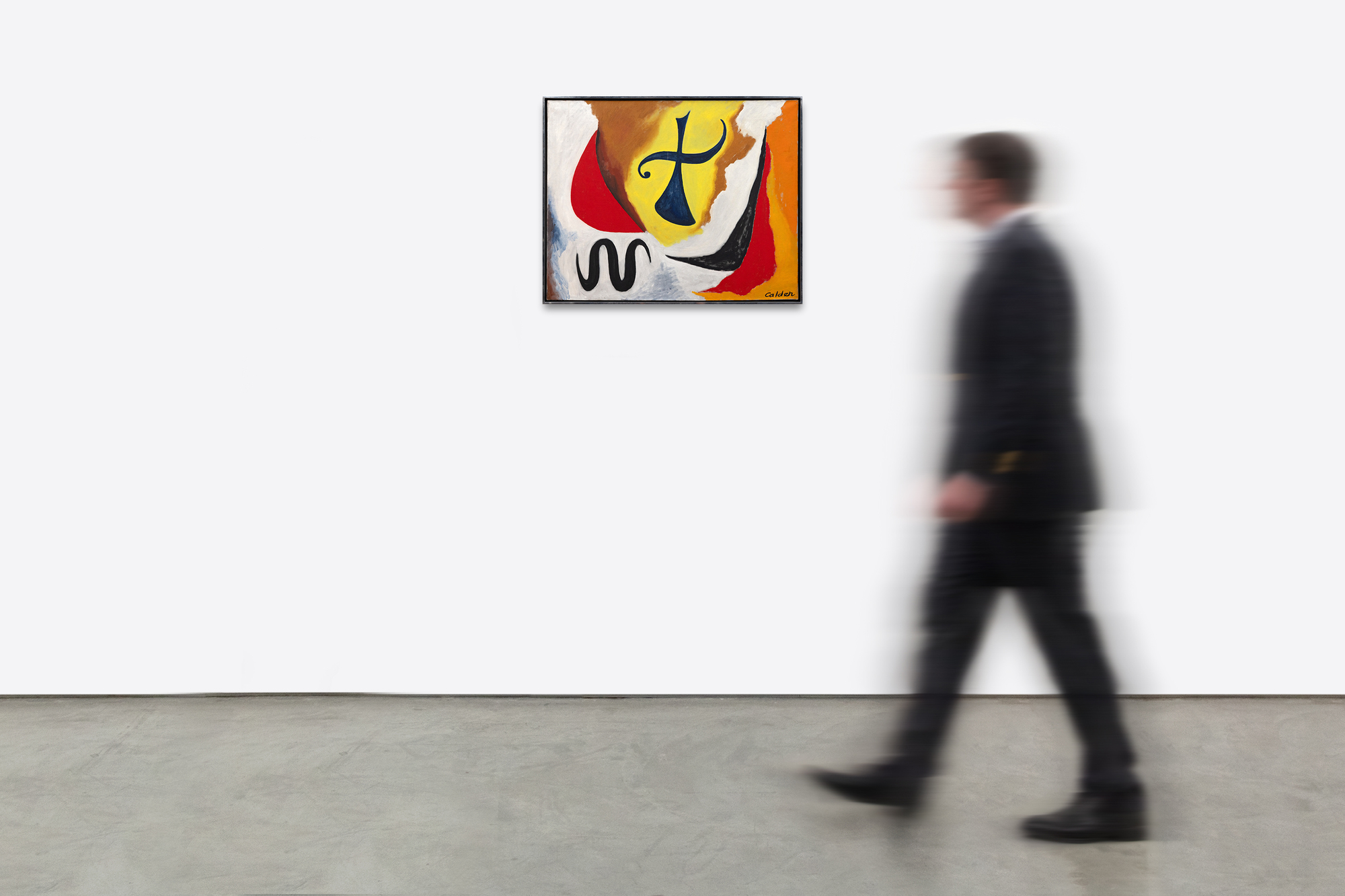

亚历山大-考尔德在20世纪40年代后半期和50年代初创作了数量惊人的油画作品。此时,他在1930年访问蒙德里安工作室时受到的冲击,即他不是被画作而是被环境所打动,已经发展成为考尔德自己的艺术语言。因此,当考尔德在1948年画《十字架》时,他已经站在了国际认可的风口浪尖上,并在1952年赢得了第二十六届威尼斯双年展的雕塑大奖。在绘画和雕塑实践中,考尔德以相同的形式语言和对形状和颜色的掌握来处理两种媒介。

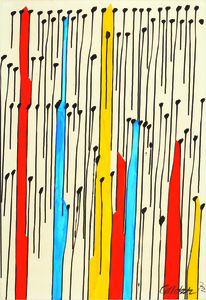

考尔德对保持物体运动的看不见的力量深感兴趣。把这种兴趣从雕塑带到画布上,我们看到,考尔德通过改变平面和平衡,在《十字架》中建立了一种扭矩感。利用这些元素,他创造了隐含的运动,暗示人物正在向前推进,甚至从天空中下降。十字架"的坚定势头被一些细节进一步放大,比如主体强调地伸出手臂,左边的拳头状曲线矢量,以及剪影的蛇形人物。

考尔德还在《十字架》的表面采用了强烈的诗意放弃的线索。这与他的好朋友米罗的层次感和明显的个人视觉语言产生了共鸣,但在这幅画的各种元素的有效动画中,它是所有考尔德的作品。没有哪位艺术家比考尔德赢得了更多的诗意许可,在他的整个职业生涯中,这位艺术家在对形式和构图的理解上保持了随和的灵活性。他甚至欢迎别人的无数种解释,他在1951年写道:"别人掌握了我的想法似乎并不重要,至少只要他们有别的东西在他们心中。

无论怎样,重要的是要记住,《十字架》是在第二次世界大战的动荡之后不久绘制的,对一些人来说,这似乎是对当时的一种清醒的反映。最重要的是,《十字架》证明了亚历山大-考尔德首先用他的画笔描绘了关于形式、结构、空间关系以及最重要的运动的想法。

市场情报

- 伦敦艺术市场研究公司的图表显示,自 1976 年 1 月以来,考尔德的艺术品价值增长了 3474.3%,复合年增长率为 7.6。

- 虽然考尔德是一位多产的艺术家,但像《十字架》这样的布面油画是该艺术家作品中最罕见的例子。

同类拍卖的画作

"Personnage"(1946年)以1,865,000美元成交。

- 画在《十字架》的两年前

- 类似的颜色,但《十字架》中的抽象概念更有亲和力

- 这幅画于2014年在拍卖会上售出,今天的价值将远远超过300万美元。

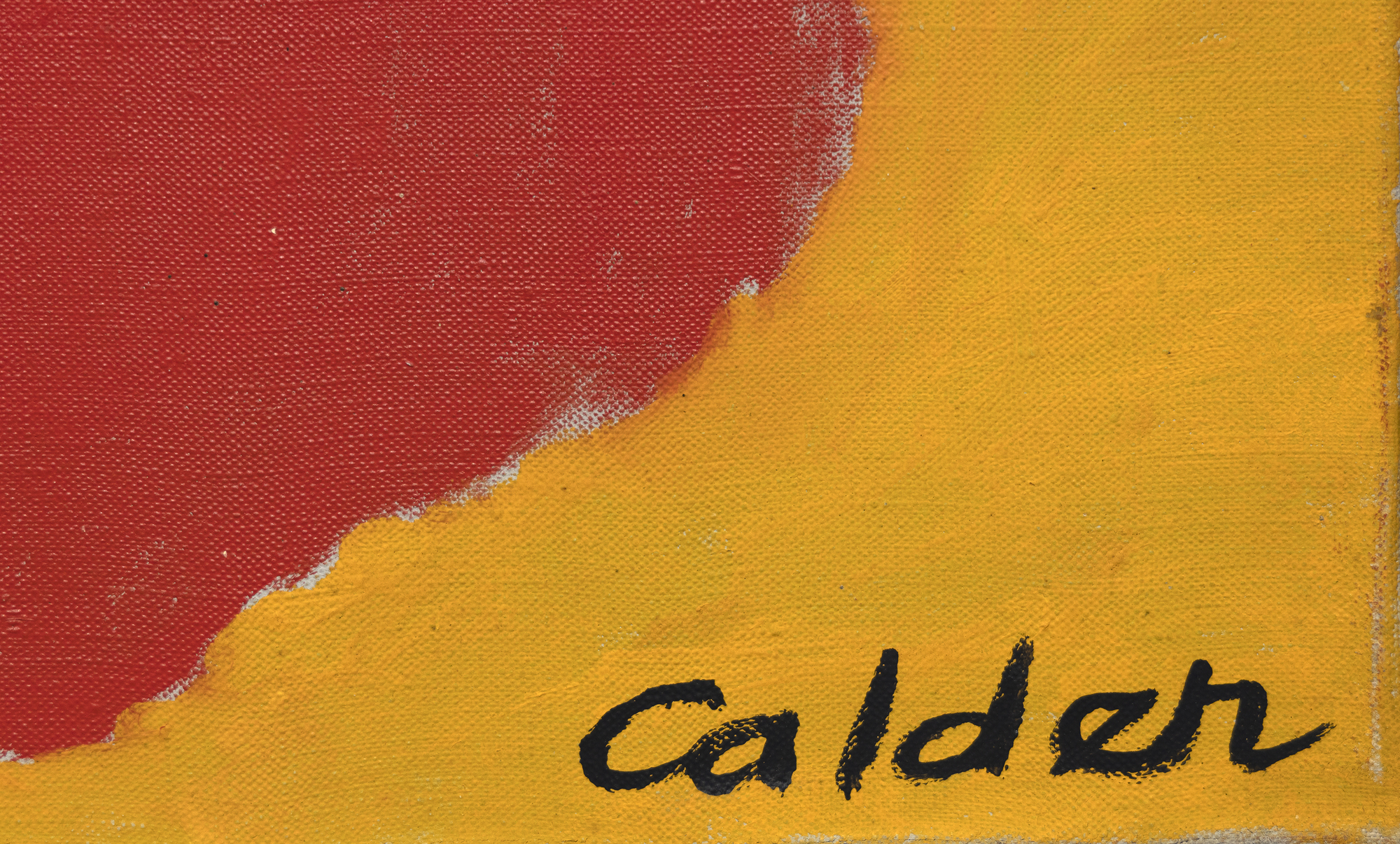

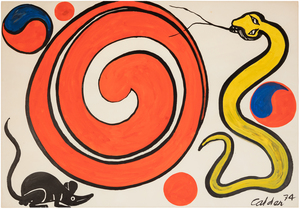

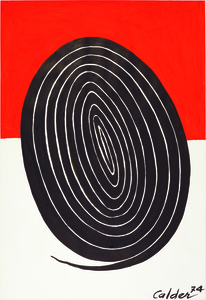

"Fond rouge"(1949年)以1,815,000美元成交。

- 在《十字架》之后仅一年的时间里绘制的

- 一个不错的抽象作品,但在构图上没有《十字架》那么激动人心。

- 这里的背景只有一种颜色,而《十字架》的背景则平衡了多种色调。