Join Heather James Fine Art Director, Tom Venditti, as he tours our flagship gallery in Palm Desert, California. We feel fortunate to have Tom. Prior to joining Heather James Fine Art, Tom spent 14 years as the Senior Director of Art for the breathtaking Paul Allen Collection, which recently set several new records at auction in a triumphant display of the art market’s strength.

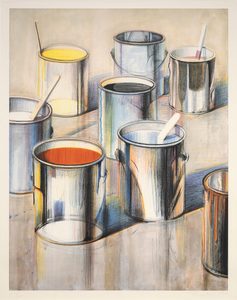

Heather James Fine Art endeavors to offer a wide selection of art of historical significance and aesthetic appeal and we can think of no one more capable of providing insights into a Claude Monet while seamlessly offering an informed perspective on a fabulous, new arrival by Wayne Thiebaud. We hope you enjoy Tom’s curated journey across several genres and blue-chip artists and that it will inform you and inspire a visit to our Palm Desert location to view the collection in person.

We are pleased to announce our winter hours at our Palm Desert location at 455188 Portola Avenue: Monday through Saturday from 9:00 – 5:00.

_tn43950.jpg )

_tn27035.jpg )

_tn45106.jpg )

_tn27843.jpg )

_tn46214.jpg )

_tn46616.jpg )

_tn28596.jpg )

_tn46213.jpg )

_tn40803.jpg )

_tn36185.jpg )

_tn37425.jpg )