Picasso: Beyond the Canvas

“The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web.” – Pablo Picasso

ARTWORK

Picasso: Beyond the Canvas

ABOUT

Few artists have become as synonymous with art itself as Pablo Picasso. Picassos’ innovation and creativity has reached across cultures and societies. Not content with mastering one medium, Picasso sought out new vehicles in which to express his vision of the world. He experimented with a variety of media, using his drawings, the printing process, and even ceramics to explore and push his art making.

Marking the 50th anniversary since Picasso’s death, Heather James presents an exhibition that touches on some of Picasso’s most important works that shows his creativity and experimentation beyond the canvas.

“Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.” – Pablo Picasso

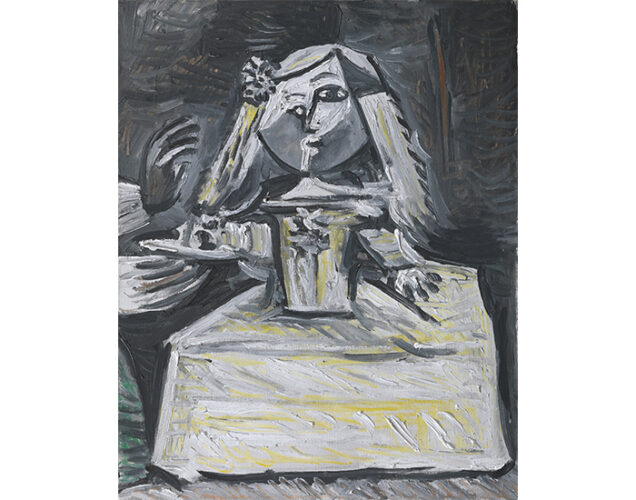

DRAWINGS

Often obscured by his pioneering style, Picasso was an accomplished draftsman whose clarity of line is most apparent in his drawings. Drawing was an important component of Picasso’s process. It is through drawing and linework that Picasso could conceptualize three-dimensional space onto the two-dimensional surface, complicating the viewer’s relationship with visual and temporal perspective.

The exhibition features a drawing that captures a favored theme of Picasso – the bath. Filled with sensuous female nudes, scenes of bathing allowed Picasso to create intimate compositions that recalled classical friezes. Bathers were not just popular with Picasso, as other artists including Paul Cézanne and Georges Seurat were drawn to the subject. As we will see with a later work, Picasso was not just a disruptor of art history but emphasized his place within its cannon.

CERAMICS

Towards the end of the 1940s, Picasso began creating ceramic artworks in earnest. In 1946, looking to challenge himself and impressed by the quality of the ceramics produced by Madoura in Vallauris, France, he began a collaboration with the owners, Suzanne and Georges Ramié. Vallauris in the south of France has been a center for ceramics since the Romans. Picasso and Madoura were a fruitful collaboration, spanning 25 years and producing over 600 works.

The malleable medium offered Picasso the opportunity to explore his ideas of form in three dimensions. Picasso enjoyed the unpredictable nature of ceramics – the fickle firing process, the mercurial change of colored glaze under heat. Ceramics helped connect Picasso to his Mediterranean heritage in which he incorporated into these objects – Greek mythological figures, animals like owls, and corridas or bullfighting scenes. Picasso, helped by the experts of Madoura, could experiment with glazes, slips, and oxides as he played with form and function.

The ceramics covered everything from mold-pressed plates to thrown objects like vases and jugs. Jules Agard threw the ceramics to Picasso’s specification which Picasso then took to assemble, alter, and decorate.

Not just a creative outlet, the ceramics were intended to be a more accessible entry point for a wider audience to collect Picasso’s work.

LINOCUTS AND ETCHINGS

Even towards the end of his life, Picasso continued to push himself. Only at the age of 77 did he create his first linocuts. The Bust of a Woman, after Cranach the Younger (1958) was Picasso’s first color linocut. The process of creating linocuts (prints created from cutting and pressing a piece of linoleum) is a time-consuming process; each color requires a different block. Registering each block correctly is incredibly difficult with misalignments often occurring. With the assistance and knowledge of Hidalgo Arnera, Picasso and Arnera created a new method for creating multicolor linocut prints that utilized only one block which minimized misalignments. However, this meant that after each successive printing, they could not backtrack. Although Cranach does not use this method, it was a pivotal work that showed the complexity with which Picasso worked.

Going beyond the technique of printmaking, Cranach is a prime example of Picasso’s fondness to re-interpret works by Old Master painters. In a sense, Picasso was like a composer creating variations on a theme – think Paul Hindemith composing Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber. By re-interpreting works, Picasso presents his own vision of the themes by Old Masters while also putting himself in dialogue with their works. These conversations deconstruct and reconstruct ideas of influence and the act of painting itself. The most important of these re-interpretations is Picasso’s Las Meninas which remixes Diego Velázquez’s work in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. The series was begun in 1957, the year before Cranach. Other artists including Richard Hamilton even re-imagine Picasso’s own interpretation of Las Meninas.

“Go and do things you can’t. That is how you get to do them.” – Pablo Picasso

INQUIRE

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

ARTISTS