FIRST CIRCLE: CIRCLES IN ART

First Circle: Circles in Art takes an expansive view of the recurrence of circles in art in the last 100 years. Although the works included belong to Modern and Contemporary art, the exhibition considers how the longer history of this symbolic shape influenced practitioners of the 20th and 21st century. From Anish Kapoor to Franz Kline, Richard Pousette-Dart to Suh Se Ok, the exhibition crosses the globe to showcase this ever-present geometry.

The exhibition opens with the quote by one of the United States’ first philosophers, Ralph Waldo Emerson. The quote captures the power of the circle and its place – not just within nature but that nature within us. There is no distinction between the natural world and humans. We should see the dignity and possibilities within ourselves and others. It is not a static condition but a dynamic process

“The eye is the first circle; the horizon which it forms is the second; and throughout nature this primary figure is repeated without end. It is the highest emblem in the cipher of the world.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

ARTWORK

First Circle: Circles in Art

ABOUT

A BRIEF HISTORY

Circles and their varied symbolisms have been prevalent in art for millennia. While it would be impossible to cover every possible meaning of circles in art, this section will lay out a selection of diverse and interconnecting significances. This glimpse provides background for the exhibition and the way Modern and Contemporary artists have utilized this potent sign.

Since circles have no starting or ending point, the shapes often represent an eternal rotation. For example, one of the earliest circles to appear in art is the ouroboros which depicts a snake or serpent devouring its own tail. Starting in Ancient Egypt before transferring to Ancient Greece, the ouroboros represents the cycle of life and renewal on a cosmic level.

The shape also came to be represented in Buddhism as the dharmachakra or wheel of darma, the religion’s most important symbol. The wheel often represented Buddha’s teaching or Buddha himself and points to the turning of the wheel, signifying a revolutionary change. In Buddhism, prayer wheels are often used.

The turning of the wheel is also seen in Western cultures via the wheel of fortune or rota fortuna. This symbol of fate demonstrates the everchanging positions of human fate where misfortune may follow great success. Whether for individuals or for civilizations, the wheel of fortune has been a potent metaphor depicted in art.

However, circles may not always be illustrated on such grand levels. Imagine the symbolism of a ring – fidelity and power. From engagement rings to coronation rings, this small piece of jewelry has been utilized in art and literature to carry meaning as varied as unending love, true friendship, or the might of a nation.

“I trace your circle, I give you yourself. I have made you the greatest window upon God.” – Richard Pousette-Dart

RICHARD POUSETTE-DART

Richard Pousette-Dart was one of the leaders of Abstract Expressionism. The non-representational movement placed primacy on artists and their mark making. Within this movement, Pousette-Dart was also a member of “The Irascibles”, a group of artists that protested the exhibition “American Painting Today – 1950” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art because of the show’s emphasis on figuration.

What separated Pousette-Dart from the other AbEx artists was his expression of spiritual ideal. Like other Western artists drawn to their immediate, abstract nature, Pousette-Dart found inspiration in the cultures of the African continent including Egypt as well as Native American art. This searching across cultures for a common artistic and cultural thread is observed in other artists within First Circle.

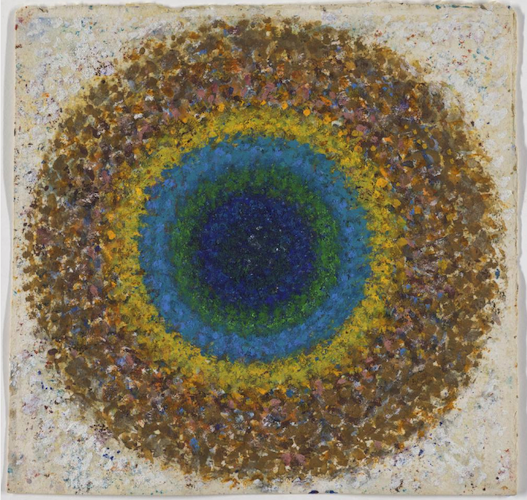

By the 1950s and 1960s, the artist moved to a more pointillist style but still maintained a fascination with the circle. Pousette-Dart referred to the circle as “the compass of eternity” because of its association with eternal life. Not just in painting, Pousette-Dart experimented with the shape in other mediums, including drawings them and cutting them out of brass. Even the use of painted points is its own kind of circle. The New York City Hospitals system commissioned Pousette-Dart for work which would ultimately become Presence, Healing Circles. The painting is part of the NYC Health + Hospitals collection of 4,000 works, which aims to create a calming, supportive environment for patients and their families. Circles unite, circles heal.

The work in the exhibition exemplifies Pousette-Dart’s exploration of circles. The many circles and spirals seem to dance across the canvas, a radiance of suns expressed through the miniature circles that are dots. Even the suggestion of an Egyptian symbol in the upper left resembles the Eye of Horus; the eye is, after all, the first circle found in nature as Emerson notes, and this work, consistent with much of Pousette-Dart’s oeuvre, aligns with Emerson’s Transcendentalism. With this painting, the artist reaches into the cosmos to contemplate eternity.

EAST IS EAST AND WEST IS WEST

This section explores the artists exploring the intersection of cultures and the symbolic nature of the circle.

One of the artists who was deeply inspired in finding a universal language of symbols was Jae Kon Park. Park was a post-World War II modernist who immigrated from his native South Korea to South America in search of ubiquitous symbols across nations and time.

Park theorized that art began with lines and dots transformed into the sacred circle, which he saw as a Mandala and as a motif that spanned cultures from the Aztec and Inca Empire to China to Hinduism. For more about Jae Kon Park, visit our exhibition, Jae Kon Park: Life and Root or enjoy our catalogue.

Another interesting piece in the exhibition is Anish Kapoor’s wall sculpture whose title, Halo, invokes not just a circle but its symbolic nature. Kapoor layers this by using a pleated mirror and thus layering the medium’s long and potent history and meaning. The circular mirror is a theme the artist would return to multiple times in his career.

From halos to Mandalas, a sacred sun or a vision of eternity, artists have tapped into cross-cultural circles. They have contemplated the nature of life through the universal nature of circles.

“I’ve always wanted my work to be clear. The circle is a form from Nature – one of the most common forms for humans, one that we can’t avoid. So the circle is easy to understand and needs no explanation to appreciate.” – Tadasky Kuwayama

THE RESPONSIVE EYE

More than a trick of the eye, Optical Art or Op Art is a movement that went to the basics of visual art – how do we perceive? What are the essential parts of a work of art? What is the relationship of colors and shapes to each other? While the movement can trace its roots to previous generations like the Pointillists, Cubist, and Neo-Constructivists, it was the 1965 landmark exhibition The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that put Op Art on the map.

The incredibly popular show exhibited artists as varied as Frank Stella and Bridget Riley in addition to some of the most important Op Art artists including Francis Celentano, Wojciech Fangor and Tadasky Kuwayama. First Circle brings together these three artists to explore their use of circles.

For Celentano, the shape is a vehicle to explore how the eye perceives shapes and lines. Again, we see the insight of Emerson when he declared the eye as the first circle for its own shape as well as its ability to observe within the cycle of nature.

For Fangor, the circle was a doorway into a deeper exploration of the cosmos, of the spatial relationship of color. The edge of the shape dissolves into canvas even as the shape hints at infinity – a balance of disintegration and permanence. Fangor observed that “circles and waves are useful because they are deprived of angles and have continuous structure.” No other geometry would work.

Perhaps of these three artists, Tadasky has the most in common with Emerson as seen in the above quotes. The circle is both a creation of Tadasky’s universe and of nature in general. We can also see a relationship to mandalas in Tadasky’s painting process. Sitting on a board above the painting, the artist creates each ring in a single spin, pushing the limits of his body and of his concentration through the meditation of paint, color, and shape. It is also important to note how Tadasky places the circle within the square, further underscoring its link to mandalas and to the mathematical impossibility of squaring the circle.

IN THE ABSTRACT

The final section is dedicated to artists who approach circles in abstract terms. Take for example, Hassel Smith. Well-known for his Abstract Expressionist paintings, Smith’s longest series are his Measured Paintings. Smith utilized a system of his devising to create meticulous but organic geometrical abstractions, many of which include circles. Like the Op Art works, these paintings are activated once the viewer observes them, trying to work out the relationship of colors and shapes, the primary of which is the circle.

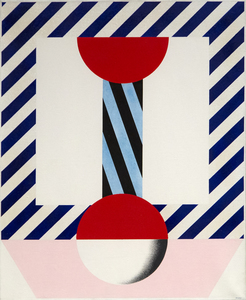

Although known for his geometric works invoking the thrill and tension of driving on a motorway, Kumi Sugai began to simplify his works to the bare essentials. The work in the exhibition demonstrates this transitory period as Sugai strips down the painting to lines and circles.

Adolph Gottlieb is most famed for his burst paintings in which circular “bursts” in a field of color are juxtaposed against expressionistic brushwork. The painting in the exhibition straddles that line while also nodding to zones separating the sky and earth. Even the title of the piece, Azimuth, references the heavens.

Rounding out the section are a series of gouaches by Alexander Calder. Calder transfers the vocabulary of his three-dimensional sculptures onto a two-dimensional surface, choreographing a dance of primary shapes, cardinal among them the circle.

Circles are all around us and within us. It is nature at its most balanced and harmonic. From globes to clocks, from the celestial music of the spheres to the sun and planets, circles have formed and inspired artists for centuries. Even in the rapid change of the 20th and 21st century, artists turned to the circle to find new meaning and new symbolism joining themselves to millennia of history.