No Other Land: A Century of American Landscapes

ARTWORK

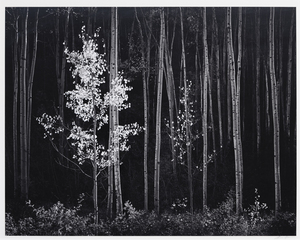

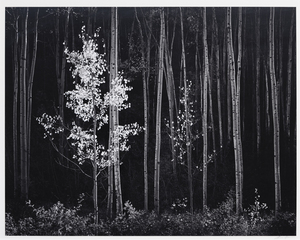

“No man has the right to dictate what other men should perceive, create or produce, but all should be encouraged to reveal themselves, their perceptions and emotions, and to build confidence in the creative spirit.” – Ansel Adams

ABOUT

What do you picture in your mind when you hear the word landscape? Heather James Fine Art presents No Other Land: A Century of American Landscapes, exploring the American landscape as a genre from different perspectives including movements, theories, time, and place. In the hierarchy of painting – the systemization of art begun during the Renaissance – landscape occupied a lower position, beating only animals and still lifes (learn more about still lifes in our exhibition, Florals for Spring, Groundbreaking).

For many, landscapes are simple paintings of the outdoors, just depictions that should realistically reflect nature. Nevertheless, landscapes, particularly of America, became a lens through which we can understand its complex geographic, cultural, social, and political identity.

This exhibition looks at almost 150 years of American landscapes, revealing certain themes and ideas that speak as much to a natural environment as well as to the artists and an everchanging nation. In painting landscapes of the United States, artists shaped the cultural and visual identity of a burgeoning nation, particularly as it grappled with the aftermath of a civil war. Each work asks us to tackle deep, existential questions: What is America? Who is America for? What does it mean to see nature?

One of the most important artists to capture the American landscape is Ansel Adams. By utilizing Adams as a central artist and comparing different artists and movements to Adams we are able to get a better understanding of both his impact and the various ways that artists have proposed questions in an effort to comprehend nature.

“The American landscape has no foreground and the American mind no background.” – Edith Wharton

RECONSTRUCTING AN IDENTITY

Winslow Homer is considered, even during his lifetime, one of America’s greatest painters. Gilded Age art critic Frederic Morton wrote, “There is something rugged, austere, even Titanic in almost everything Homer has done.” As the United States emerged from the Civil War, the public and art world looked to Homer and other artists to define and work through what America was. Homer became a touchstone as he painted women at leisure and children at play and then the brash New England seascapes. Around him, critics lauded that he created art away from European influences. While not strictly true, Homer captured different aspects of a nation rebuilding itself and the changes in his art style traces how the nation looked upon itself.

While renowned for his masculine, austere New England landscapes of the late 1800s, in the 1870s, Homer painted almost exclusively women and children. He depicted contemporary life while also moving away from narratives, a change from Academic paintings which placed emphasis on history paintings. This emphasis on the everyday explored America as it was in that era.

The works in the exhibition show not only the daily lives of the nation but also Homer’s mastery of different medium and his use of color and composition. We see the richness and bounty of the land and as a setting for leisurely pastime.

“The trick, then, is not to decide that the place we’ve chosen is worthy of us, but to care about all the places you never thought of as beautiful or important or profound. Because every place, it turns out, is somebody’s home ground.” – Robert Sullivan

A GUILDED TIME

Stretching from the end of the Civil War and ending roughly with the outbreak of WWI, the Gilded Age defined modern American identity. Against a background of upheavals in the economy, robber barons and captains of industry propelled unprecedented levels of wealth as well as poverty.

During the Gilded Age, art flourished, bolstered by the newly rich and reflecting the seismic shifts in the socio-political spheres. Artists of this time looked to capture the changes in America, solidifying the country’s thoughts of itself as it grew and took an increasing global role.

The mural painting in the show highlights Frieseke as one of the leaders of the American Impressionists. Celebrated for his light dappled paintings, Frieseke utilizes a combination of brushstrokes to create distinctions of pattern and light in this work while visually depicting the nation’s growing middle class. Dig deeper and we begin to understand the wealth of industrialists to commission these works. This painting was commissioned by department store magnate and founder of the Professional Golfers Association Rodman Wanamaker as part of a mural for the Grand Deluxe Shelburn hotel in Atlantic City.

Emerging at the end of the period, N.C. Wyeth became one of the most celebrated and beloved artists. Wyeth produced around 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books; his popular illustrated series for publishing company Charles Scribner’s Sons came to be known as Scribner’s Classics and remain in print to this day filling our imaginations. Through his paintings and illustrations, Wyeth helped shaped the U.S. thought of itself.

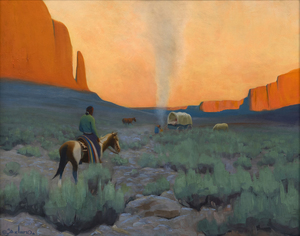

“Summer “Hush” (1909) is a quietly powerful painting of a Native American figure, which comes from a quartet of works representing the four seasons. Wyeth’s painting is a continuation of the complex relationship between the United States and Native American tribes along with the depiction of Native Americans in art. Wyeth’s painting is part of the trend that moved from negative depictions into a romanticization of Native Americans at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In discussing the four seasons paintings, Wyeth notes that he is “so much interested in—the ‘primitive Indian.’”

For more about this time period and its relation to art history, visit our exhibition, A Beautiful Time: American Art in the Gilded Age.

“My painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me.” – Georgia O’Keeffe

O’KEEFFE AND ADAMS

Although not as widely known, Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams enjoyed a fruitful friendship. While working in different mediums, O’Keeffe and Adams transformed Modern art and landscapes. Looking at similar vistas or regions, they individualized their view of the American landscape, shaping our understanding of America and Modernism. Despite this shared appreciation of the landscape, their personalities and approach to making art could not be starker.

The American Southwest looms large in the imagination of the country, a place of majestic beauty and wild freedom. This is partly due to the art of both Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams but what brought them to this region? O’Keeffe came west to escape New York and Alfred Stieglitz; Adams, to step outside California, broaden his focus, and to meet East Coast artists like O’Keeffe. In an odd way, it was America’s two coasts coming together.

In bringing together O’Keeffe and Adams within the context of the American landscape, we can understand their differing approaches to composition and to how they approach the subject.

Visit our exhibition, Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Modern Art, Modern Friendship, for a more in depth look at their relationship and its effect on their work and on art history.

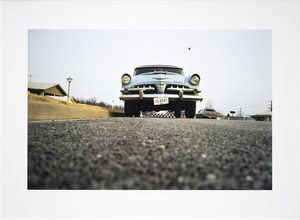

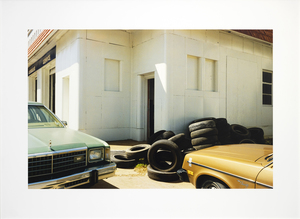

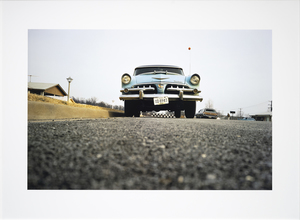

“Often people ask what I’m photographing, which is a hard question to answer. And the best what I’ve come up with is I just say: Life today.” – William Eggleston

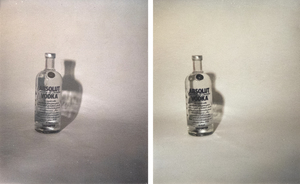

ADAMS OR EGGLESTON

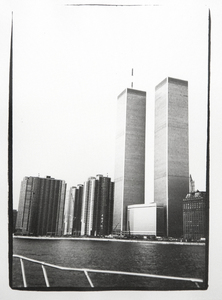

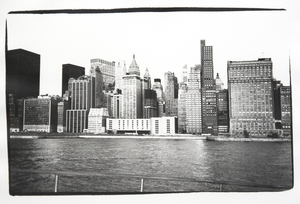

Despite being titans of photography in America, Ansel Adams and William Eggleston have not often been exhibited together, most likely because many focus on their differences rather than their similarities. In bringing the two together, the exhibition looks to highlight how each approached photography and the American landscape. Where Adams looked to the majestic and natural, Eggleston focused on the quotidian and urban. Where Adams took black and white photography to new heights, Eggleston upended our view of color photography from the amateur family photograph to a respected medium. Adams thought there was too much conflict between how film captured color and how people perceived color or reacted to color.

Adams even ungenerously quipped, “I find little substance. For me, [Eggleston’s photographs] appear to be observations, floating on a sea of his consciousness. For me, most draw a blank.” Art critic Adrian Searle points to the key difference, “You look into Adams’s photographs. You look at Eggleston’s.” Adams presents photographs not a flat surface but as a window through which to observe a landscape. Eggleston presents scenes to puzzle over and unpack.

Nevertheless, in bringing the two artists together, we see a bigger picture of America, its contradictions, its dreams, its ideals, and its faults. We see two artists mining photography for all it could do, pushing technique as far as possible.

Emerging at the end of the period, N.C. Wyeth became one of the most celebrated and beloved artists. Wyeth produced around 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books; his popular illustrated series for publishing company Charles Scribner’s Sons came to be known as Scribner’s Classics and remain in print to this day filling our imaginations. Through his paintings and illustrations, Wyeth helped shaped the U.S. thought of itself.

“Summer “Hush” (1909) is a quietly powerful painting of a Native American figure, which comes from a quartet of works representing the four seasons. Wyeth’s painting is a continuation of the complex relationship between the United States and Native American tribes along with the depiction of Native Americans in art. Wyeth’s painting is part of the trend that moved from negative depictions into a romanticization of Native Americans at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In discussing the four seasons paintings, Wyeth notes that he is “so much interested in—the ‘primitive Indian.’”

For more about this time period and its relation to art history, visit our exhibition, A Beautiful Time: American Art in the Gilded Age.

“The future always looks good in the golden land, because no one remembers the past.” – Joan Didion

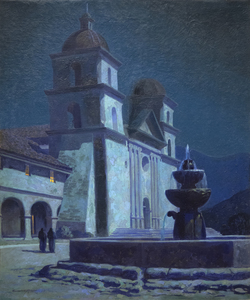

CALIFORNIA DREAMING

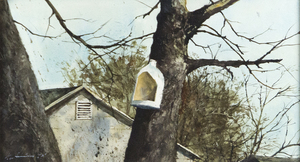

While the Impressionism that originally sprang from Paris focused on modern, urban life, the Impressionism that took root in California revolved around its tremendous landscape. Only California could nurture a style of Impressionism that focused so spectacularly on its unique environment. The visual vocabulary of the Old World would have to adapt to a new setting. With its dramatic coastline, its majestic mountains, dense forests, deep canyons, and everything in between, California could provide artists an endless source of inspiration. But it wasn’t just the landscape that provided the movement it’s unique quality. The artists worked in close knit art groups including the California Art Club, whose original members included William Wendt and Edgar Payne, and the Laguna Beach Art Association which is now the Laguna Art Museum. Get an in-depth look in our exhibition California Here We Come: The California Impressionists.

The California Impressionists were not the only innovators. Northern California would be home to a generation of artists that challenged the predominant and pervasive abstraction and abstract expressionism of Post-War America. The Bay Area Figurative artists found psychological and aesthetic depths through figuration, returning the focus back onto figures and representation, challenging abstraction as the forefront of avant-garde art. These artists reincorporated subject and representation not just in rebellion to abstraction but in search for a deeper artistic fulfilment.

But perhaps two of the most prominent artists capturing California were Ansel Adams and Wayne Thiebaud. Few artists are as closely related to Yosemite as Adams. For Thiebaud, the San Francisco and the Sacramento Delta provided a fertile inspiration for him to create paintings of intense colors and shapes that were as much about landscapes as they were about the process of painting itself.

INQUIRE

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

ARTISTS