Please contact the gallery for more information.

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2016

2015

2014

2011

2010

2009

History

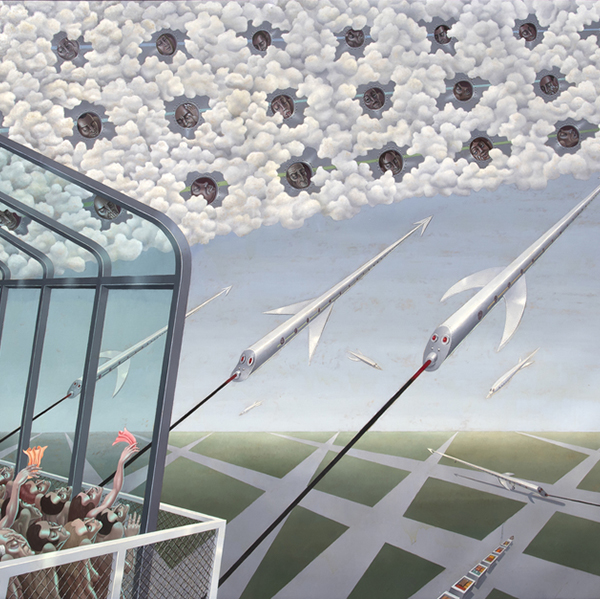

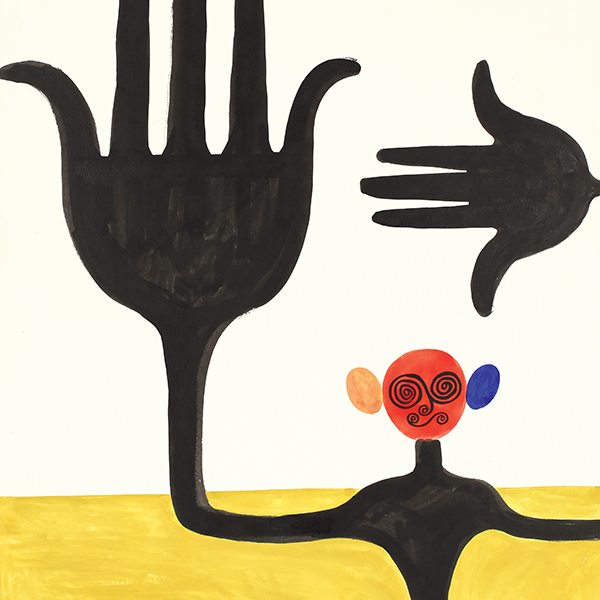

On an autumn afternoon in 1909, twenty-one-year-old Giorgio de Chirico was sitting alone on a bench at the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence. He was not feeling well. But as he looked across the piazza, a profound, overwhelming sensation came over him. It was as if he could see through the materiality of the world for the first time. “The whole world, down to the marble of the buildings and fountains, seemed to me to be convalescent”, he explained — (Giorgio de Chirico, Meditations of a Painter, 1912) mere physical manifestations of more profound worlds full of hidden meanings. The experience inspired him to try to paint analogous imagery to capture the “eternal moment”, a concept he derived from his reading of Nietzsche. But as an artist with a well-known knack for self-promotion and self-mythologizing, De Chirico is also the artist intent upon never allowing us to forget that his early strangely lit paintings of empty streets and squares oddly populated by classical sculptures, towers and passing steam trains are the true precursors and inspiration for Surrealism.

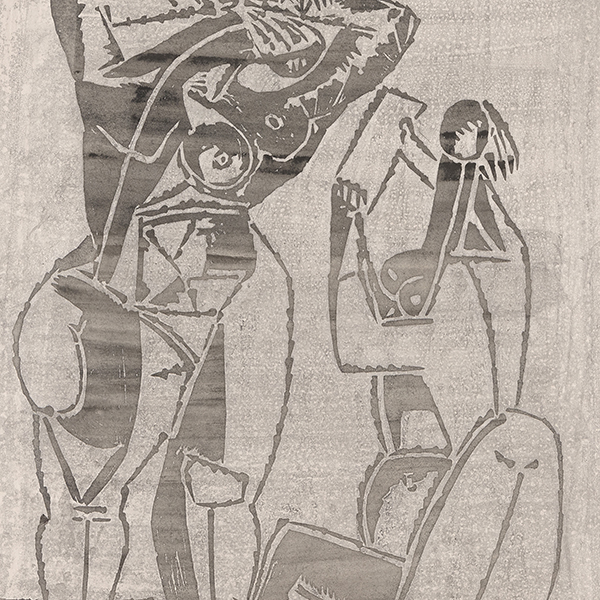

The Disquieting Muses was painted in Ferrara Italy in 1918. A renaissance city of great artistic and cultural heritage, de Chirico’s arrival here was a product of fate not choice. While it is important to appreciate the impact Chirico’s newly anointed Metaphysical paintings had on the circle of artists and writers that gathered around Apollinaire when he lived in Paris from 1911 to 1914, it is here, as a wartime conscript in Ferrara under the shadow of the imposing fortress Castello Estense that he developed upon a novel vocabulary to augment the hauntingly perplexing settings, new techniques of light and shadows and startling, enigmatic perspectives. Here, he would embellish those attributes with flattened spaces, geometric boxes or frames, and a variety of new motifs including the most conspicuous of all: the mannequin-like figures characterized by art historian Roberto Longhi as Frankenstein-like monstrosities. From a contemporary perspective, these figures might seem far more robotic characters in a science fiction story. But some have speculated that the faceless figures recall the prosthetics built to hide the grotesque deformities brought on by trench warfare along the western front. For certain, in 1917, de Chirico’s fragile state of mind had compelled influential friends to see that he was relived of official duties and admitted to Villa del Seminario, a military hospital near Ferrara where the chief of the institution assigned him a room he could use as a studio. It is here, in this room that this version of Le Muse Inquietanti (The Disquieting Muses) was likely painted. And it is here, that de Chirico embarked upon this, and other extraordinary depictions of prophetic mannequin figures dressed in classical clothing; often of one standing, another sitting and placed amongst various objects including a red mask and staff, an allusion to Melpomene and Thalia, the muses of tragedy and comedy.

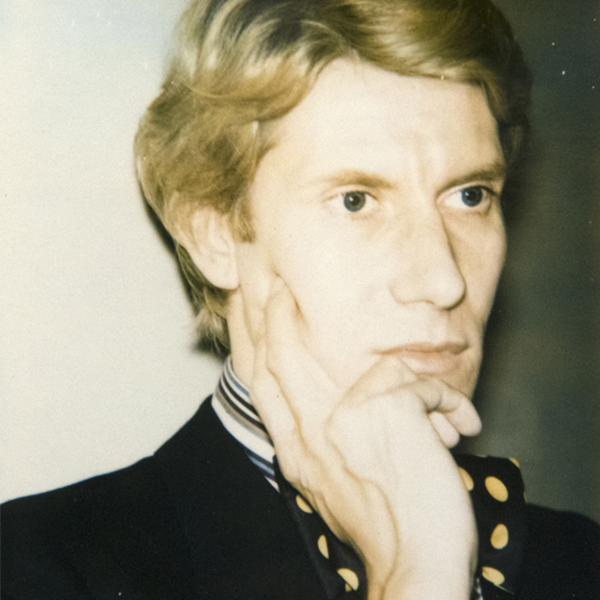

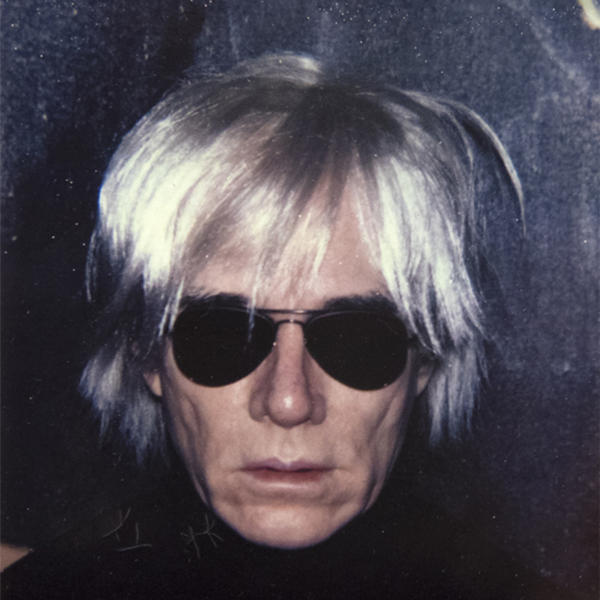

André Breton was a great admirer of the painting, and any discussion of The Disquieting Muses must include its notoriety as a serial work, replicated on numerous occasions. The first reprised version was created at the request of poet Paul Éluard who, in 1924 asked to purchase it only find that it had already sold. Picasso was also a great admirer of the work. It is known that he purchased a notebook of de Chirico’s sketches for The Disquieting Muses during the mid-1930s. Nor can it go without notice that Andy Warhol greatly admired the similarities in their working methods. Upon seeing Museum of Modern Art director William Rubin’s reproduction in the exhibition catalogue of eighteen nearly identical versions of the painting displayed as two-page spread, Warhol recognized a kindred spirit. Like Warhol, De Chirico had been lambasted for using repetition as a money-making enterprise. But he also had his defenders. To quote the Italian art critic Achille Bonito Oliva, “de Chirico viewed repetition as a way of expressing himself” and the list of artists who recognize the relevance of the artist’s late work to current approaches to art must include Richard Prince, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, Mike Bidlo and many, many others.

Top Results at Auction

Comparable Paintings Sold at Auction

Paintings in Museum Collections

Image Gallery

Additional Resources

Inquire

You May Also Like