Palm Desert

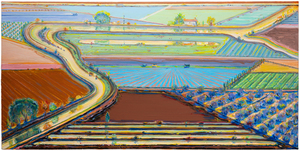

Our gallery in Palm Desert is centrally located in the Palm Springs area of California, adjacent to the popular shopping and dining area of El Paseo. Our clientele appreciates our selection of Post War, Modern, and Contemporary art. The gorgeous weather during the winter months draws visitors from all over the world to see our beautiful desert, and stop by our gallery. The mountainous desert landscape outside provides the perfect scenic backdrop to the visual feast that awaits inside.

45188 Portola Avenue

Palm Desert, CA 92260

(760) 346-8926

Hours:

Monday – Saturday 9am to 5pm

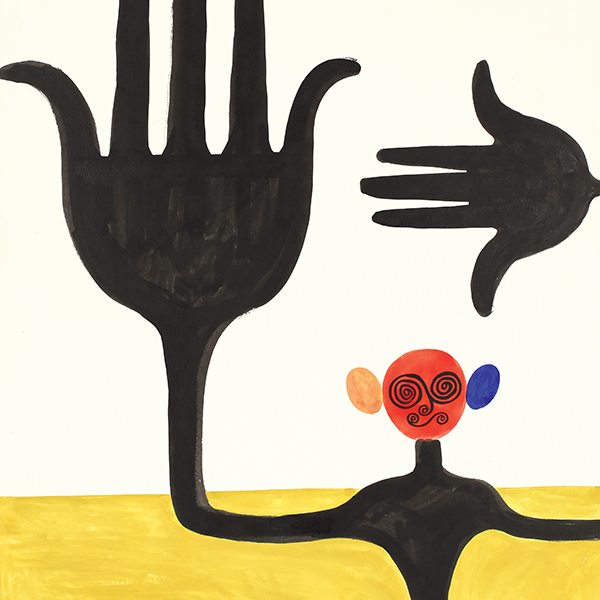

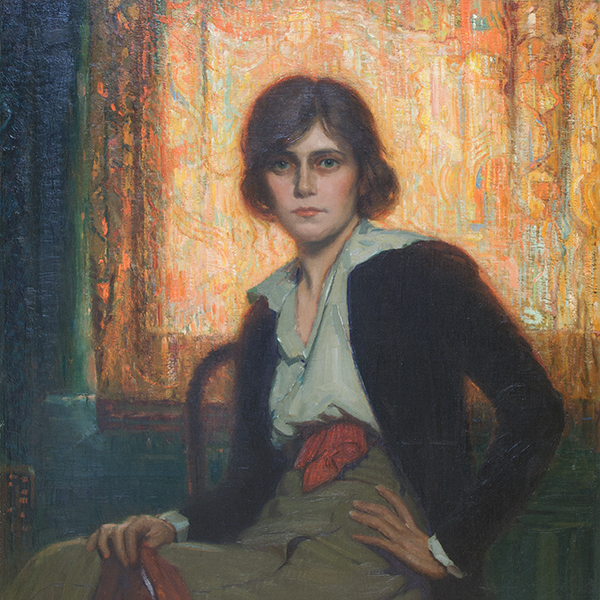

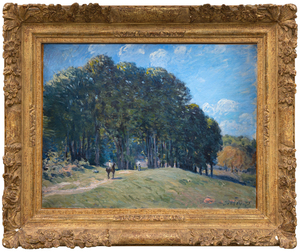

Exhibitions

ARCHIVE

Your Heart’s Blood: Intersections of Art and Literature

ARCHIVE

More to Life: Impressionist Dialogues from Monet and Beyond

ARCHIVE

Jewish Modernism Part 2: Figuration from Chagall to Norman

ARCHIVE

Vincent van Gogh and The Great Impressionists of the Grand Boulevard

ARTWORK ON VIEW

CONSULTANTS

MONTANA ALEXANDER

Chairman, Global Director

Palm Desert, California

Montana Alexander is a distinguished leader in the international art world, serving as Chairman and Global Director of Heather James. Based at the flagship gallery in Palm Desert, California, Montana oversees the entire company’s operations and drives its global vision. Her 2025 move back to Palm Desert from New York City represents a deliberate step to deepen connections within the thriving desert art scene and to further elevate Heather James’ influence on the West Coast.

Since joining Heather James in 2013, Montana has been instrumental in expanding the gallery’s reach into the global secondary art market, shaping company-wide strategy, and cultivating relationships with an elite roster of collectors—from major members of the ArtNews 200 to emerging art patrons. Her discerning eye and passion for excellence have guided significant acquisitions of works by iconic artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Claude Monet, and Mark Bradford.

Montana’s leadership was pivotal in securing the landmark acquisition of the Post-War and Contemporary art collection from the General Electric Company Corporate Art Collection—one of the most significant corporate collections to enter the secondary market. She was also behind critically acclaimed exhibitions like “The Female Gaze,” featuring female surrealists including Frida Kahlo and Leonora Carrington, and “The Paintings of Sir Winston Churchill,” a touring show developed in collaboration with Churchill’s family estate.

Holding a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Business Management from the University of Connecticut and a postgraduate certificate in Art Business from Sotheby’s Institute in New York, Montana blends academic rigor with hands-on expertise. Her visionary leadership continues to shape Heather James into a dominant force on the global art stage, while her recent move to Palm Desert signals a bold new chapter for the gallery’s growth and influence.

ERIC ARTECHE

Fine Art Consultant

Palm Desert, California

Eric Arteche is a Fine Art Consultant with Heather James Fine Art in Palm Desert, CA, bringing over 10 years of sales experience working with top clients and Fortune 500 companies. Eric’s background includes a Bachelor’s of Arts in Social Science and History from Westmont College and a Master’s of Science in Resilient and Sustainable Communities from Green Mountain College. A constant desire to learn and grow led Eric to the art world, starting in Research and Operations and now partnering directly with clients to find the perfect pieces for their collections. Outside of the gallery, Eric loves to spend time with his family, explore new restaurants, take road trips, and roast his own coffee.

IN THE NEWS

SERVICES

Heather James Fine Art provides a wide range of client-based services catered to your specific art collecting needs. Our Operations team includes professional art handlers, a full registrar department and logistical team with extensive experience in art transportation, installation, and collection management. With white glove service and personalized care, our team goes the extra mile to ensure exceptional art services for our clients.

GET TO KNOW US

CONTACT

_tn43950.jpg )

_tn39755.b.jpg )

_tn45106.jpg )

_tn27843.jpg )

_tn46214.jpg )

_tn48062.jpg )

_tn22479.jpg )

_tn16764.b.jpg )

_tn40803.jpg )

,_new_mexico_tn40147.jpg )