Désert de palmier

Notre galerie à Palm Desert est située au centre de la région de Palm Springs en Californie, à côté de la zone commerçante et salle à manger populaire d'El Paseo. Notre clientèle apprécie notre sélection d'art d'après-guerre, moderne et contemporain. Le temps magnifique pendant les mois d'hiver attire les visiteurs de partout dans le monde pour voir notre beau désert, et s'arrêter à notre galerie. Le paysage désertique montagneux à l'extérieur offre la toile de fond panoramique parfaite à la fête visuelle qui vous attend à l'intérieur.

45188, avenue Portola

Palm Desert, Californie 92260

(760) 346-8926

Heures d'ouverture :

Du lundi au samedi : 9h00 - 17h00

Expositions

ARCHIVES

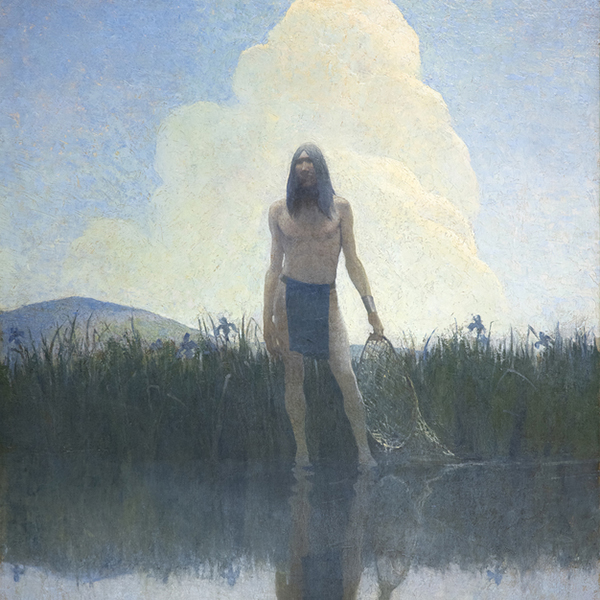

Rencontre avec la vie : N.C. Wyeth et les fresques de MetLife

ARCHIVES

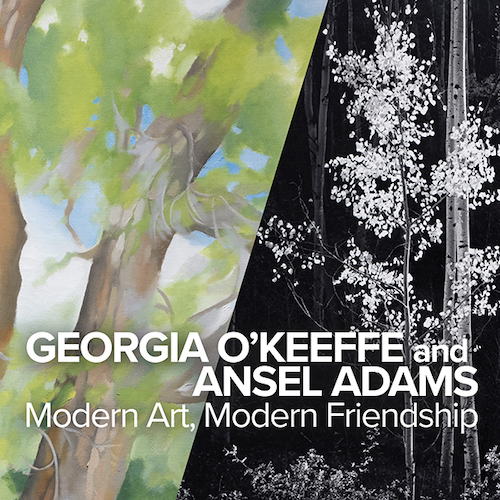

Georgia O'Keeffe et Ansel Adams : Art moderne, amitié moderne

ARCHIVES

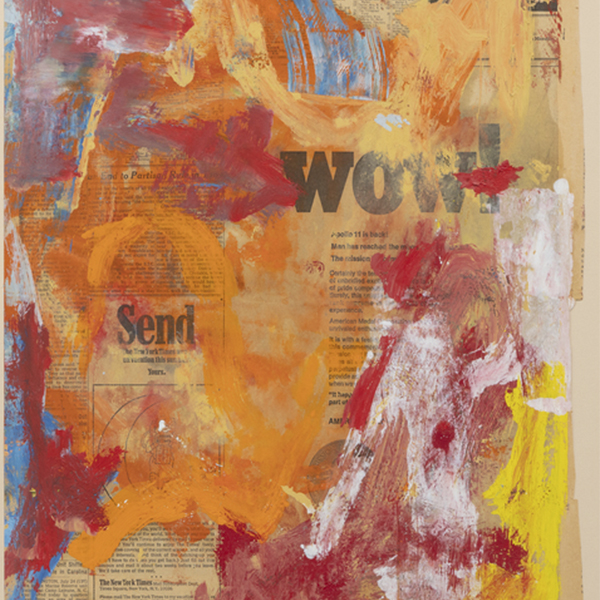

Le sang de votre cœur : Intersections de l'art et de la littérature

ARCHIVES

Des fleurs pour le printemps, un coup de pied dans la fourmilière

ARCHIVES

Plus que de la vie : Dialogues impressionnistes de Monet et au-delà

ARCHIVES

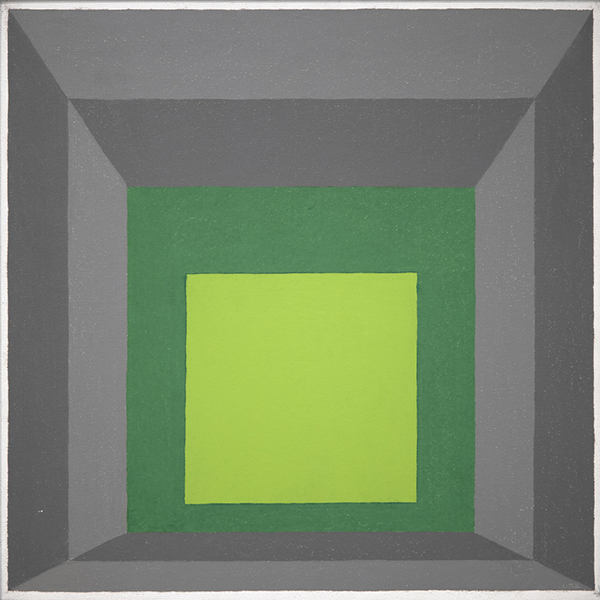

Le modernisme juif - Partie 2 : La figuration de Chagall à Norman

ARCHIVES

Vincent van Gogh et les grands impressionnistes du Grand Boulevard

ARCHIVES

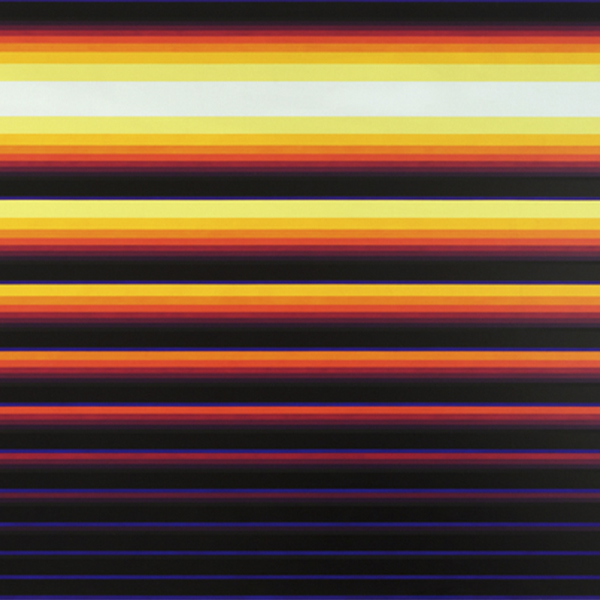

Ferrari et Futuristes : Un regard italien sur la vitesse

OEUVRED-ŒUVRE SUR LA VUE

DANS LES NOUVELLES

SERVICES

Heather James Fine Art offre une vaste gamme de services à la clientèle qui répondent à vos besoins particuliers en matière de collection d'œuvres d'art. Notre équipe d'exploitation comprend des gestionnaires d'œuvres d'art professionnels, un service de registraire complet et une équipe logistique possédant une vaste expérience du transport, de l'installation et de la gestion des collections d'œuvres d'art. Avec un service de gants blancs et des soins personnalisés, notre équipe fait un effort supplémentaire pour assurer des services artistiques exceptionnels à nos clients.

_tn27843.jpg )

_tn46214.jpg )

_tn39239.jpg )

_tn28596.jpg )

_tn47033.jpg )

_tn16764.b.jpg )

_tn40803.jpg )

_tn47012.jpg )

,_new_mexico_tn40147.jpg )

_tn43950.jpg )