Veuillez contacter la galerie pour plus d'informations.

Expositions en cours

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2016

2015

2014

2011

2010

2009

Histoire

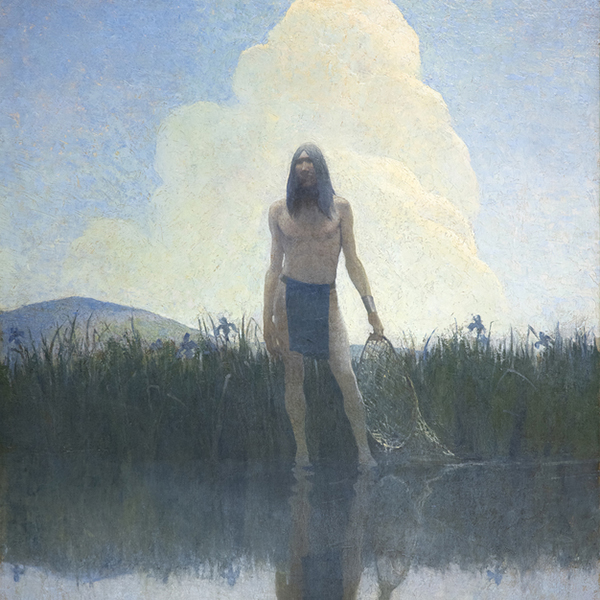

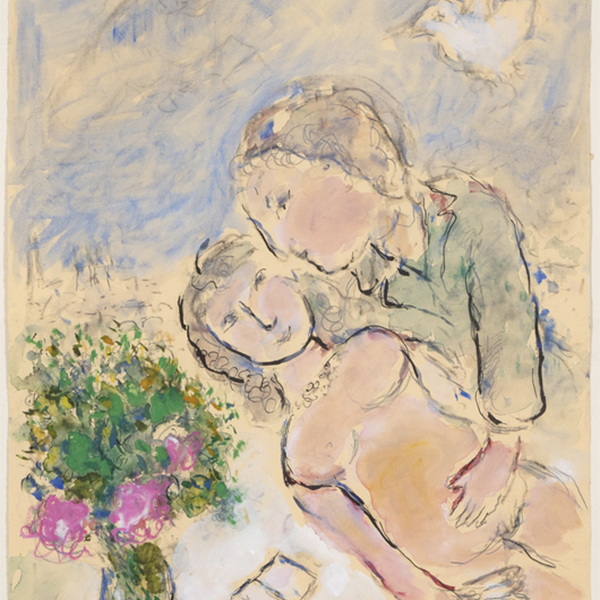

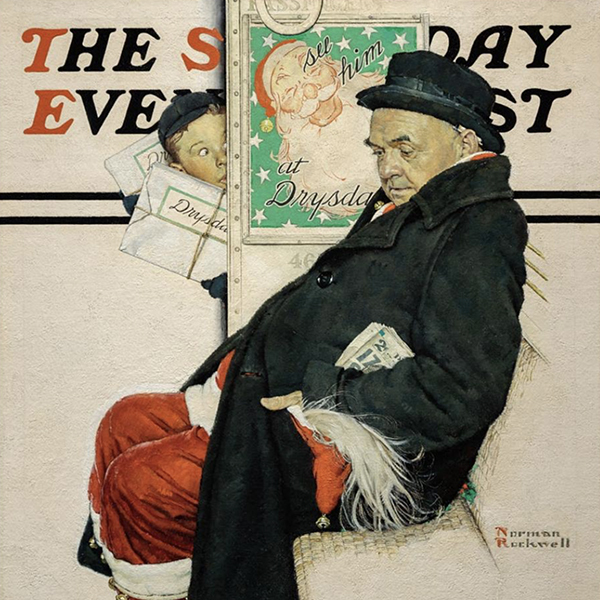

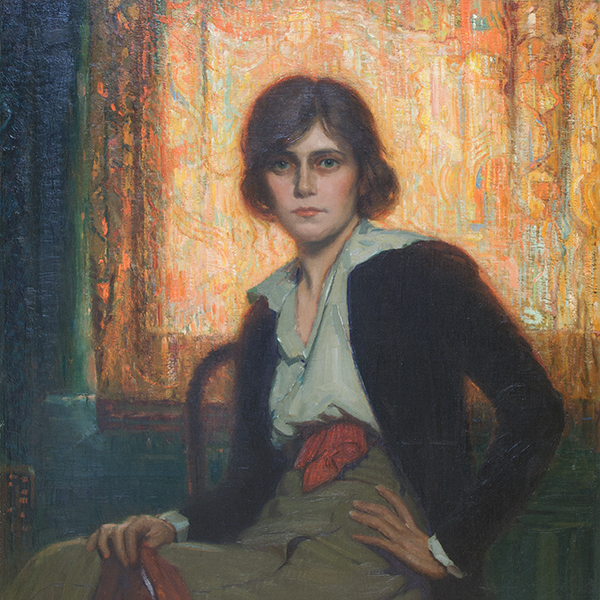

Dès les débuts de la peinture au XIXe siècle, précipités par l'avènement de l'impressionnisme, Renoir s'est forgé une réputation de meilleur portraitiste parmi les paysagistes émergents. Des œuvres telles que Lise à l'ombrelle (1867) démontrent sa capacité à capturer l'essence de ses sujets avec un flair particulier, ce qui le distingue de ses pairs. Inspiré par un voyage transformateur en Italie en 1882, Renoir change d'approche, mettant l'accent sur le modelé et les contours avec une manipulation douce et mélangée, intégrant une nouvelle rigueur et une clarté rappelant les anciens maîtres. Souvent qualifié de "période Ingres", Renoir conserve la réputation du peintre le plus apte à gérer le processus traditionnel d'enregistrement de la ressemblance d'un modèle avec le flair distinctif et l'éclat d'un impressionniste.

En 1890, le style de Renoir évolue à nouveau. Il dilue ses pigments pour obtenir une translucidité semblable à celle d'un bijou, conférant à ses œuvres une qualité tendre et éthérée. Cette dernière phase reflète les limites physiques de l'arthrite rhumatoïde, mais aussi une approche plus profonde et plus réfléchie de ses sujets, capturant leur lumière intérieure et leur caractère avec des touches subtiles et lumineuses.

N'étant plus obligé de répondre aux commandes de portraits de la société, Renoir se concentre dès 1900 sur les portraits et les études de sa famille, de ses amis proches et de ses voisins. Fillette à l'orange, peint en 1911, élargit notre appréciation de son style très personnel et intime et de sa réputation d'imprégner ses portraits d'enfants de tout le charme affectueux qu'il pouvait rassembler. Il évite l'approche plus douce et généralisée qui a incité son fils Jean à dire que "nous sommes tous les enfants de Renoir, des versions idéalisées de la beauté et de la sensualité exprimées de manière universelle plutôt qu'avec des spécificités physionomiques". Nous ne connaîtrons peut-être jamais son identité, mais sa ressemblance est frappante parce que Renoir se concentre sur son visage et son expression. Néanmoins, le jeu de la lumière et de la couleur met en valeur ses traits et donne vie à la nature tendre et affectueuse caractéristique des derniers portraits de Renoir. L'orange en tant qu'accessoire est souvent incluse dans les portraits comme symbole de fertilité. Pourtant, ici, elle semble servir d'élément formel permettant à l'artiste de démontrer son habileté à mettre en valeur sa taille, sa forme et son poids dans la main de cette jeune fille.

APERÇU DU MARCHÉ ET DÉTAILS CLÉS

Selon Art Market Research, basé à Londres, les prix du marché de Renoir ont augmenté à un taux de croissance annuel composé de 5,5 % depuis 1976.

Les peintures des dernières années de Renoir, y compris celles représentant des enfants, sont relativement rares par rapport à ses premières œuvres. Cette rareté ajoute à leur attrait et peut contribuer à augmenter les prix de vente aux enchères lorsqu'elles sont mises sur le marché.

Les tableaux de Renoir, en particulier ses portraits d'enfants, sont connus pour leur chaleur, leur humanité et leur attrait intemporel. De la fin des années 1870 aux années 1880, Renoir a fait évoluer son approche de la peinture d'enfants, dépassant l'impressionnisme pour incorporer des formes structurées et une palette plus riche.

Dans les dernières années de sa vie, en particulier à partir des années 1890, les portraits d'enfants de Renoir reflètent un style classique et raffiné influencé par les maîtres anciens, visant à une qualité intemporelle.

En utilisant des couleurs vibrantes et des effets de lumière nuancés, Renoir met en valeur la chaleur et la vitalité de ses enfants, comme le montre Fillette à l'orange. Renoir aborde ses portraits d'enfants avec sensibilité, capturant la personnalité et le caractère uniques de chaque sujet, alliant la maîtrise technique à la profondeur émotionnelle.

_tn43950.jpg )